Article of the Week... Toon of the Week... Coming Soon on SkS... Climate Feedback Claim Review... SkS Week in Review...Poster of the Week...

Article of the Week...

June 2019: Earth's Hottest June on Record

In this picture taken on June 6, 2019, Hindu priests sit inside large vessels filled with water as they perform the 'Parjanya Japa' and offer prayers to appease the rain god for timely monsoons at the Huligamma Devi Temple in Koppal District, some 300 km from Bangalore, India. A 33-year-old man died after a fight over water in southern India, police said on June 7, as huge parts of the country gasped from drought and a brutal summer heatwave. The heat wave was blamed for 210 deaths in June, making it Earth’s deadliest weather-related disaster of the month. Image credit: STR/AFP/Getty Images.

June 2019 was the planet's warmest June since record keeping began in 1880, said NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) on Tuesday. NASA also rated June 2019 as the warmest June on record, well of ahead of the previous record set in 2015.

The global heat in June is especially impressive and significant given that only a weak (and weakening) El Niño event was in place. As human-produced greenhouse gases continue to heat up our planet, most global heat records are set during El Niño periods, because the warm waters that spread upward and eastward across the surface of the tropical Pacific during El Niño transfer heat from the ocean to the atmosphere.

Global ocean temperatures during June 2019 were tied with 2016 for warmest on record, according to NOAA, and global land temperatures were the warmest on record. Global satellite-measured temperatures in June 2019 for the lowest 8 km of the atmosphere were the warmest or second warmest in the 41-year record, according to RSS and the University of Alabama Huntsville (UAH), respectively.

As of July 15, July 2019 was on track to be the warmest month in Earth’s history (in absolute terms, not in terms of temperature departure from average)--just ahead of the record set in July 2017.

June 2019: Earth's Hottest June on Record by Jeff Masters, Category 6, Weather Underground, June 18, 2019

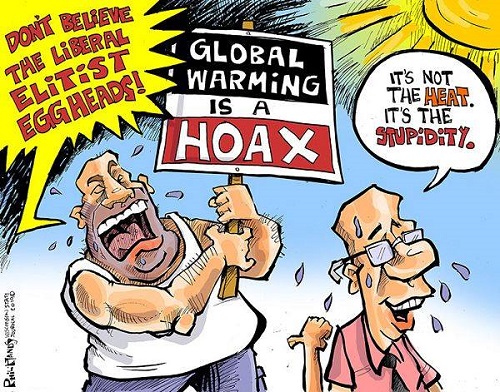

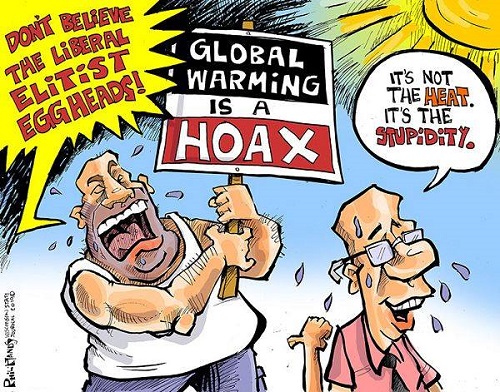

Toon of the Week...

Coming Soon on SkS...

- CCC: UK has just 18 months to avoid ’embarrassment’ over climate inaction (Simon Evans)

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #29, 2019 (SkS Team)

- Analysis: How Trump’s rollback of vehicle fuel standards would increase US emissions (Zeke Hausfather)

- What psychotherapy can do for the climate and biodiversity crises (Caroline Hickman)

- How climate change is making hurricanes more dangerous (Jeff Berardelli)

- 2019 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #30 (John Hartz)

- 2019 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming Digest #30 (John Hartz)

Climate Feedback Claim Review...

Sky News Australia interview falsely claims that global cooling is coming soon

CLAIM:

"the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is misleading humanity about climate change and sea levels, and that in fact a new solar-driven cooling period is not far off"

SOURCE:

New sun-driven cooling period of Earth ‘not far off’, Alan Jones interviews Nils Axel-Mörner, Sky News Australia, June 2019

VERDICT:

![]()

DETAILS:

Inadequate Support: These claims contradict all the available data and published research on these topics. There is no support in the scientific literature for the claim that solar activity could significantly cool the climate in the decades to come.

KEY TAKE AWAY:

Scientists have established that observed climate change and sea level rise are clearly caused by human activities, primarily the emission of carbon dioxide through the burning of fossil fuels. Solar activity cannot explain recent warming, and even the occurrence of low solar activity in the near future would have an insignificant effect on human-caused warming.

Sky News Australia interview falsely claims that global cooling is coming soon, Edited by Scott Johnson, Claim Reviews, Climate Feedback, July 18, 2019

SkS Week in Review...

- 2019 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #29 by John Hartz

- 97% consensus study hits one million downloads! by John Cook

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #28, 2019 by SkS Team

- 10 things a committed U.S. President and Congress could do about climate change by Craig K Chandler (Yale Climate Connections)

- 2019 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming Digest #28 by John Hartz

Poster of the Week...

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/2YgkFWW

Article of the Week... Toon of the Week... Coming Soon on SkS... Climate Feedback Claim Review... SkS Week in Review...Poster of the Week...

Article of the Week...

June 2019: Earth's Hottest June on Record

In this picture taken on June 6, 2019, Hindu priests sit inside large vessels filled with water as they perform the 'Parjanya Japa' and offer prayers to appease the rain god for timely monsoons at the Huligamma Devi Temple in Koppal District, some 300 km from Bangalore, India. A 33-year-old man died after a fight over water in southern India, police said on June 7, as huge parts of the country gasped from drought and a brutal summer heatwave. The heat wave was blamed for 210 deaths in June, making it Earth’s deadliest weather-related disaster of the month. Image credit: STR/AFP/Getty Images.

June 2019 was the planet's warmest June since record keeping began in 1880, said NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI) on Tuesday. NASA also rated June 2019 as the warmest June on record, well of ahead of the previous record set in 2015.

The global heat in June is especially impressive and significant given that only a weak (and weakening) El Niño event was in place. As human-produced greenhouse gases continue to heat up our planet, most global heat records are set during El Niño periods, because the warm waters that spread upward and eastward across the surface of the tropical Pacific during El Niño transfer heat from the ocean to the atmosphere.

Global ocean temperatures during June 2019 were tied with 2016 for warmest on record, according to NOAA, and global land temperatures were the warmest on record. Global satellite-measured temperatures in June 2019 for the lowest 8 km of the atmosphere were the warmest or second warmest in the 41-year record, according to RSS and the University of Alabama Huntsville (UAH), respectively.

As of July 15, July 2019 was on track to be the warmest month in Earth’s history (in absolute terms, not in terms of temperature departure from average)--just ahead of the record set in July 2017.

June 2019: Earth's Hottest June on Record by Jeff Masters, Category 6, Weather Underground, June 18, 2019

Toon of the Week...

Coming Soon on SkS...

- CCC: UK has just 18 months to avoid ’embarrassment’ over climate inaction (Simon Evans)

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #29, 2019 (SkS Team)

- Analysis: How Trump’s rollback of vehicle fuel standards would increase US emissions (Zeke Hausfather)

- What psychotherapy can do for the climate and biodiversity crises (Caroline Hickman)

- How climate change is making hurricanes more dangerous (Jeff Berardelli)

- 2019 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #30 (John Hartz)

- 2019 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming Digest #30 (John Hartz)

Climate Feedback Claim Review...

Sky News Australia interview falsely claims that global cooling is coming soon

CLAIM:

"the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is misleading humanity about climate change and sea levels, and that in fact a new solar-driven cooling period is not far off"

SOURCE:

New sun-driven cooling period of Earth ‘not far off’, Alan Jones interviews Nils Axel-Mörner, Sky News Australia, June 2019

VERDICT:

![]()

DETAILS:

Inadequate Support: These claims contradict all the available data and published research on these topics. There is no support in the scientific literature for the claim that solar activity could significantly cool the climate in the decades to come.

KEY TAKE AWAY:

Scientists have established that observed climate change and sea level rise are clearly caused by human activities, primarily the emission of carbon dioxide through the burning of fossil fuels. Solar activity cannot explain recent warming, and even the occurrence of low solar activity in the near future would have an insignificant effect on human-caused warming.

Sky News Australia interview falsely claims that global cooling is coming soon, Edited by Scott Johnson, Claim Reviews, Climate Feedback, July 18, 2019

SkS Week in Review...

- 2019 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #29 by John Hartz

- 97% consensus study hits one million downloads! by John Cook

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #28, 2019 by SkS Team

- 10 things a committed U.S. President and Congress could do about climate change by Craig K Chandler (Yale Climate Connections)

- 2019 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming Digest #28 by John Hartz

Poster of the Week...

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/2YgkFWW