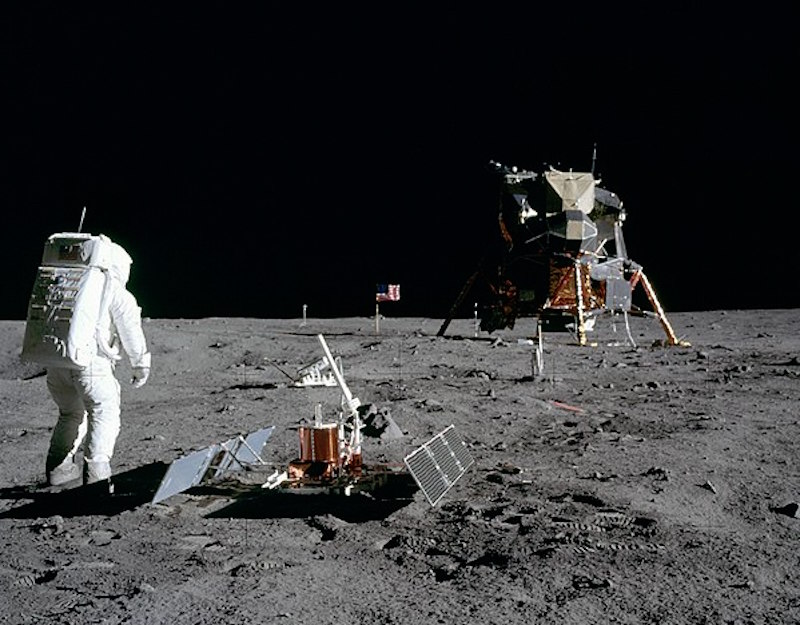

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission. Image via Neil Armstrong/NASA.

Jean Creighton, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Much of the technology common in daily life today originates from the drive to put a human being on the moon. This effort reached its pinnacle when Neil Armstrong stepped off the Eagle landing module onto the lunar surface 50 years ago.

As a NASA airborne astronomy ambassador and director of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Manfred Olson Planetarium, I know that the technologies behind weather forecasting, GPS and even smartphones can trace their origins to the race to the moon.

A Saturn V rocket carrying Apollo 11 and its crew toward the moon lifts off on July 16, 1969. Image via NASA.

1. Rockets

October 4, 1957 marked the dawn of the Space Age, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first human-made satellite. The Soviets were the first to make powerful launch vehicles by adapting World War II-era long-range missiles, especially the German V-2.

From there, space propulsion and satellite technology moved fast: Luna 1 escaped the Earth’s gravitational field to fly past the moon on January 4, 1959; Vostok 1 carried the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space on April 12, 1961; and Telstar, the first commercial satellite, sent TV signals across the Atlantic Ocean on July 10, 1962.

The 1969 lunar landing also harnessed the expertise of German scientists, such as Wernher von Braun, to send massive payloads into space. The F-1 engines in Saturn V, the Apollo program’s launch vehicle, burned a total of 2,800 tons of fuel at a rate of 12.9 tons per second.

Saturn V still stands as the most powerful rocket ever built, but rockets today are far cheaper to launch. For example, whereas Saturn V cost US$185 million, which translates into over $1 billion in 2019, today’s Falcon Heavy launch costs only $90 million. Those rockets are how satellites, astronauts and other spacecraft get off the Earth’s surface, to continue bringing back information and insights from other worlds.

2. Satellites

The quest for enough thrust to land a man on the moon led to the building of vehicles powerful enough to launch payloads to heights of 21,200 to 22,600 miles (34,100 to 36,440 km) above the Earth’s surface. At such altitudes, satellites’ orbiting speed aligns with how fast the planet spins – so satellites remain over a fixed point, in what is called geosynchronous orbit. Geosynchronous satellites are responsible for communications, providing both internet connectivity and TV programming.

At the beginning of 2019, there were 4,987 satellites orbiting Earth; in 2018 alone, there were more than 382 orbital launches worldwide. Of the currently operational satellites, approximately 40% of payloads enable communications, 36% observe the Earth, 11% demonstrate technologies, 7% improve navigation and positioning and 6% advance space and earth science.

The Apollo Guidance Computer next to a laptop computer. Image via Autopilot/Wikimedia Commons.

3. Miniaturization

Space missions – back then and even today – have strict limits on how big and how heavy their equipment can be, because so much energy is required to lift off and achieve orbit. These constraints pushed the space industry to find ways to make smaller and lighter versions of almost everything: Even the walls of the lunar landing module were reduced to the thickness of two sheets of paper.

From the late 1940s to the late 1960s, the weight and energy consumption of electronics was reduced by a factor of several hundred at least – from the 30 tons and 160 kilowatts of the Electric Numerical Integrator and Computer to the 70 pounds and 70 watts of the Apollo guidance computer. This weight difference is equivalent to that between a humpback whale and an armadillo.

Manned missions required more complex systems than earlier, unmanned ones. For example, in 1951, the Universal Automatic Computer was capable of 1,905 instructions per second, whereas the Saturn V’s guidance system performed 12,190 instructions per second. The trend toward nimble electronics has continued, with modern hand-held devices routinely capable of performing instructions 120 million times faster than the guidance system that enabled the liftoff of Apollo 11. The need to miniaturize computers for space exploration in the 1960s motivated the entire industry to design smaller, faster and more energy-efficient computers, which have affected practically every facet of life today, from communications to health and from manufacturing to transportation.

4. Global network of ground stations

Communicating with vehicles and people in space was just as important as getting them up there in the first place. An important breakthrough associated with the 1969 lunar landing was the construction of a global network of ground stations, called the Deep Space Network, to let controllers on Earth communicate constantly with missions in highly elliptical Earth orbits or beyond. This continuity was possible because the ground facilities were placed strategically 120 degrees apart in longitude so that each spacecraft would be in range of one of the ground stations at all times.

Because of the spacecraft’s limited power capacity, large antennas were built on Earth to simulate “big ears” to hear weak messages and to act as “big mouths” to broadcast loud commands. In fact, the Deep Space Network was used to communicate with the astronauts on Apollo 11 and was used to relay the first dramatic TV images of Neil Armstrong stepping onto the moon. The network was also critical for the survival of the crew on Apollo 13 because they needed guidance from ground personnel without wasting their precious power on communications.

Several dozen missions use the Deep Space Network as part of the continuing exploration of our solar system and beyond. In addition, the Deep Space Network permits communications with satellites that are on highly elliptical orbits, to monitor the poles and deliver radio signals.

‘Earthrise,’ a view of Earth while orbiting the moon. Image via Bill Anders, Apollo 8/NASA

5. Looking back at Earth

Getting to space has allowed people to turn their research efforts toward Earth. In August 1959, the unmanned satellite Explorer VI took the first crude photos of Earth from space on a mission researching the upper atmosphere, in preparation for the Apollo program.

Almost a decade later, the crew of Apollo 8 took a famous picture of the Earth rising over the lunar landscape, aptly named “Earthrise.” This image helped people understand our planet as a unique shared world and boosted the environmental movement.

Earth from the edge of the solar system, visible as a minuscule pale blue dot in the center of the right-most brown stripe. Image via Voyager 1/NASA/

Understanding of our planet’s role in the universe deepened with Voyager 1’s “pale blue dot” photo – an image received by the Deep Space Network.

People and our machines have been taking pictures of the Earth from space ever since. Views of Earth from space guide people both globally and locally. What started in the early 1960s as a U.S. Navy satellite system to track its Polaris submarines to within 600 feet (185 meters) has blossomed into the Global Positioning System network of satellites providing location services worldwide.

Images from a series of Earth-observing satellites called Landsat are used to determine crop health, identify algae blooms and find potential oil deposits. Other uses include identifying which types of forest management are most effective in slowing the spread of wildfires or recognizing global changes such as glacier coverage and urban development.

As we learn more about our own planet and about exoplanets – planets around other stars – we become more aware of how precious our planet is. Efforts to preserve Earth itself may yet find help from fuel cells, another technology from the Apollo program. These storage systems for hydrogen and oxygen in the Apollo Service Module, which contained life-support systems and supplies for the lunar landing missions, generated power and produced potable water for the astronauts. Much cleaner energy sources than traditional combustion engines, fuel cells may play a part in transforming global energy production to fight climate change.

We can only wonder what innovations from the effort to send people to other planets will affect earthlings 50 years after the first Marswalk.

Jean Creighton, Planetarium Director, NASA Airborne Astronomy Ambassador, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Apollo 11 moon-landing innovations that changed life on Earth.

![]()

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/32MgzFo

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the moon during the Apollo 11 mission. Image via Neil Armstrong/NASA.

Jean Creighton, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

Much of the technology common in daily life today originates from the drive to put a human being on the moon. This effort reached its pinnacle when Neil Armstrong stepped off the Eagle landing module onto the lunar surface 50 years ago.

As a NASA airborne astronomy ambassador and director of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Manfred Olson Planetarium, I know that the technologies behind weather forecasting, GPS and even smartphones can trace their origins to the race to the moon.

A Saturn V rocket carrying Apollo 11 and its crew toward the moon lifts off on July 16, 1969. Image via NASA.

1. Rockets

October 4, 1957 marked the dawn of the Space Age, when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first human-made satellite. The Soviets were the first to make powerful launch vehicles by adapting World War II-era long-range missiles, especially the German V-2.

From there, space propulsion and satellite technology moved fast: Luna 1 escaped the Earth’s gravitational field to fly past the moon on January 4, 1959; Vostok 1 carried the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into space on April 12, 1961; and Telstar, the first commercial satellite, sent TV signals across the Atlantic Ocean on July 10, 1962.

The 1969 lunar landing also harnessed the expertise of German scientists, such as Wernher von Braun, to send massive payloads into space. The F-1 engines in Saturn V, the Apollo program’s launch vehicle, burned a total of 2,800 tons of fuel at a rate of 12.9 tons per second.

Saturn V still stands as the most powerful rocket ever built, but rockets today are far cheaper to launch. For example, whereas Saturn V cost US$185 million, which translates into over $1 billion in 2019, today’s Falcon Heavy launch costs only $90 million. Those rockets are how satellites, astronauts and other spacecraft get off the Earth’s surface, to continue bringing back information and insights from other worlds.

2. Satellites

The quest for enough thrust to land a man on the moon led to the building of vehicles powerful enough to launch payloads to heights of 21,200 to 22,600 miles (34,100 to 36,440 km) above the Earth’s surface. At such altitudes, satellites’ orbiting speed aligns with how fast the planet spins – so satellites remain over a fixed point, in what is called geosynchronous orbit. Geosynchronous satellites are responsible for communications, providing both internet connectivity and TV programming.

At the beginning of 2019, there were 4,987 satellites orbiting Earth; in 2018 alone, there were more than 382 orbital launches worldwide. Of the currently operational satellites, approximately 40% of payloads enable communications, 36% observe the Earth, 11% demonstrate technologies, 7% improve navigation and positioning and 6% advance space and earth science.

The Apollo Guidance Computer next to a laptop computer. Image via Autopilot/Wikimedia Commons.

3. Miniaturization

Space missions – back then and even today – have strict limits on how big and how heavy their equipment can be, because so much energy is required to lift off and achieve orbit. These constraints pushed the space industry to find ways to make smaller and lighter versions of almost everything: Even the walls of the lunar landing module were reduced to the thickness of two sheets of paper.

From the late 1940s to the late 1960s, the weight and energy consumption of electronics was reduced by a factor of several hundred at least – from the 30 tons and 160 kilowatts of the Electric Numerical Integrator and Computer to the 70 pounds and 70 watts of the Apollo guidance computer. This weight difference is equivalent to that between a humpback whale and an armadillo.

Manned missions required more complex systems than earlier, unmanned ones. For example, in 1951, the Universal Automatic Computer was capable of 1,905 instructions per second, whereas the Saturn V’s guidance system performed 12,190 instructions per second. The trend toward nimble electronics has continued, with modern hand-held devices routinely capable of performing instructions 120 million times faster than the guidance system that enabled the liftoff of Apollo 11. The need to miniaturize computers for space exploration in the 1960s motivated the entire industry to design smaller, faster and more energy-efficient computers, which have affected practically every facet of life today, from communications to health and from manufacturing to transportation.

4. Global network of ground stations

Communicating with vehicles and people in space was just as important as getting them up there in the first place. An important breakthrough associated with the 1969 lunar landing was the construction of a global network of ground stations, called the Deep Space Network, to let controllers on Earth communicate constantly with missions in highly elliptical Earth orbits or beyond. This continuity was possible because the ground facilities were placed strategically 120 degrees apart in longitude so that each spacecraft would be in range of one of the ground stations at all times.

Because of the spacecraft’s limited power capacity, large antennas were built on Earth to simulate “big ears” to hear weak messages and to act as “big mouths” to broadcast loud commands. In fact, the Deep Space Network was used to communicate with the astronauts on Apollo 11 and was used to relay the first dramatic TV images of Neil Armstrong stepping onto the moon. The network was also critical for the survival of the crew on Apollo 13 because they needed guidance from ground personnel without wasting their precious power on communications.

Several dozen missions use the Deep Space Network as part of the continuing exploration of our solar system and beyond. In addition, the Deep Space Network permits communications with satellites that are on highly elliptical orbits, to monitor the poles and deliver radio signals.

‘Earthrise,’ a view of Earth while orbiting the moon. Image via Bill Anders, Apollo 8/NASA

5. Looking back at Earth

Getting to space has allowed people to turn their research efforts toward Earth. In August 1959, the unmanned satellite Explorer VI took the first crude photos of Earth from space on a mission researching the upper atmosphere, in preparation for the Apollo program.

Almost a decade later, the crew of Apollo 8 took a famous picture of the Earth rising over the lunar landscape, aptly named “Earthrise.” This image helped people understand our planet as a unique shared world and boosted the environmental movement.

Earth from the edge of the solar system, visible as a minuscule pale blue dot in the center of the right-most brown stripe. Image via Voyager 1/NASA/

Understanding of our planet’s role in the universe deepened with Voyager 1’s “pale blue dot” photo – an image received by the Deep Space Network.

People and our machines have been taking pictures of the Earth from space ever since. Views of Earth from space guide people both globally and locally. What started in the early 1960s as a U.S. Navy satellite system to track its Polaris submarines to within 600 feet (185 meters) has blossomed into the Global Positioning System network of satellites providing location services worldwide.

Images from a series of Earth-observing satellites called Landsat are used to determine crop health, identify algae blooms and find potential oil deposits. Other uses include identifying which types of forest management are most effective in slowing the spread of wildfires or recognizing global changes such as glacier coverage and urban development.

As we learn more about our own planet and about exoplanets – planets around other stars – we become more aware of how precious our planet is. Efforts to preserve Earth itself may yet find help from fuel cells, another technology from the Apollo program. These storage systems for hydrogen and oxygen in the Apollo Service Module, which contained life-support systems and supplies for the lunar landing missions, generated power and produced potable water for the astronauts. Much cleaner energy sources than traditional combustion engines, fuel cells may play a part in transforming global energy production to fight climate change.

We can only wonder what innovations from the effort to send people to other planets will affect earthlings 50 years after the first Marswalk.

Jean Creighton, Planetarium Director, NASA Airborne Astronomy Ambassador, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Bottom line: Apollo 11 moon-landing innovations that changed life on Earth.

![]()

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/32MgzFo