Original Iroquois League was known as the Five Nations

My wife Alice regularly brings home the Indian Time news journal, a publication from the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation Territory in northern New York. It was with great interest that I came across an article titled Dating the Iroquois Confederacy by Bruce E. Johansen.

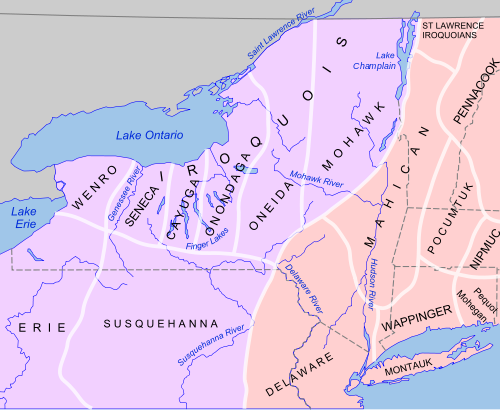

What really attracted my attention was that a total, or near total, solar eclipse marked the beginning of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, the oldest living democracy in North America and possibly on Earth. American democracy is said to have been modeled upon the democratic ideals of the Iroquois Confederacy, which originally consisted of five nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca). The sixth nation – the Tuscarora – joined the Iroquois Confederacy in the early eighteenth century (1701-1800).

Total solar eclipse of the sun on July 2, 2019

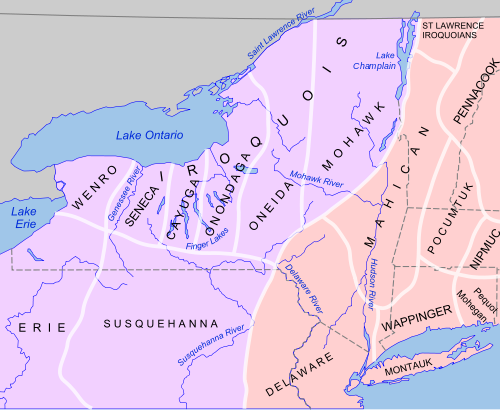

Map of the New York tribes before European arrival. Lavender indicates Iroquoian tribes. Orange indicates Algonquian tribes. Source: Smithsonian Institution

Iroquois, one of the historical figures of the Maisonneuve Monument, by Louis-Philippe Hébert, 1895, Place d’Armes, Montreal. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Bruce E. Johansen refers to the research done by Barbara A. Mann and Jerry L. Fields, which uses eclipse data as well as oral history to challenge the common notion that the Iroquois Confederacy or Iroquois League started in the fifteenth (1401-1500) or sixteenth (1501-1600) century. They state:

We know this much: During a ratification council held at Ganondagan (near modern-day Victor, New York) the sky darkened in a total, or near total, eclipse. The time of day was afternoon, as Councils are held between noon and sunset. The time of year was either Second Hoeing (early July) or Green Corn (late August to early September). Thus, we must look for an eclipse path that would totally cover Ganondagan between July and September, in mid-afternoon.

Mann and Fields settled upon the total solar eclipse of August 22, 1142 as satisfying the stated criteria. Bruce E. Johansen even pinpoints where the ratification of the Iroquois League took place:

The ratification council convened at a site that is now a football field in Victor, New York. The site is called Gonandaga by the Seneca.

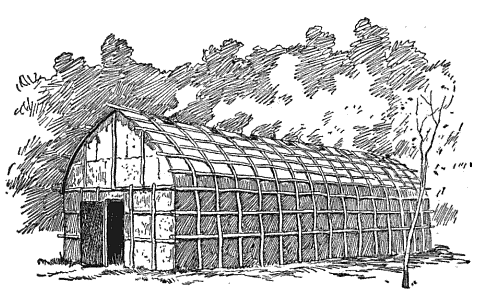

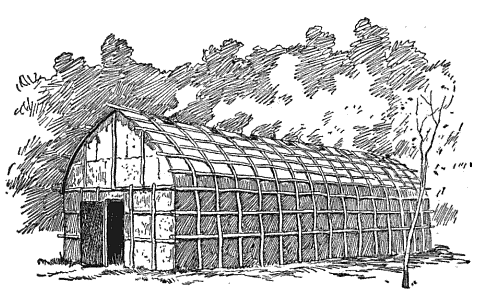

Traditional Iroquois Longhouse. Source: Wilber F. Gordy

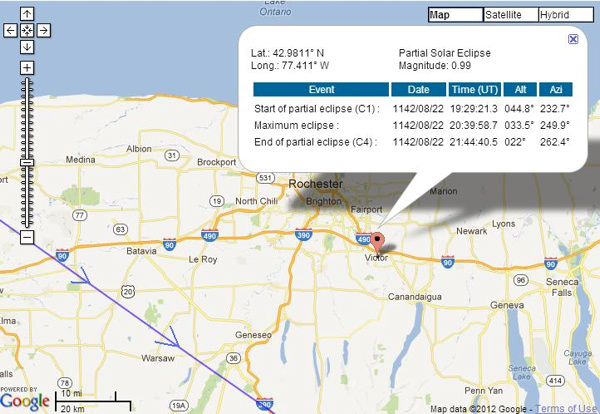

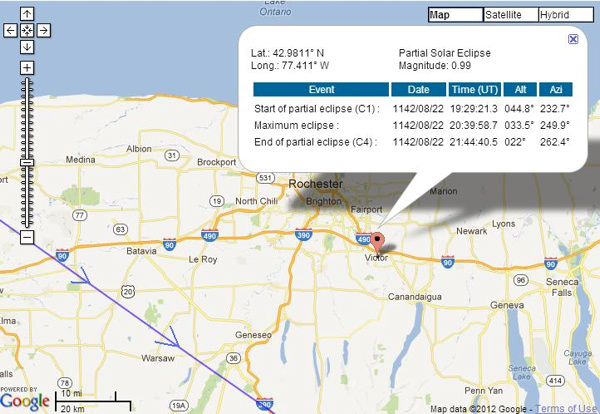

I looked up the August 1142 total solar eclipse at the NASA Eclipse Web Site. You can see this map for yourself by clicking here.

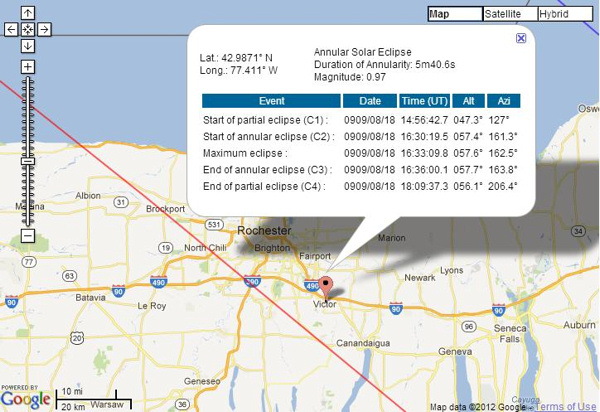

Map showing Victor, NY, and August 1142 eclipse path

Map Credit: NASA Eclipse Web Site

For the fun of it, I zoomed into the August 1142 eclipse map until finding Victor, New York. Looking along the zoomed-in eclipse path above, you can see Victor a short way to the north of the northern limit of total solar eclipse path (in blue). Nonetheless, it would have been very close to a total solar eclipse at greatest eclipse. Rounding off to the nearest minute, the partial eclipse started at 19:29 Universal Time (2:29 p.m. Eastern Standard Time), maximum eclipse arrived at 20:40 UT (3:40 p.m. EST) and the partial eclipse ended at 21:45 UT (4:45 p.m. EST).

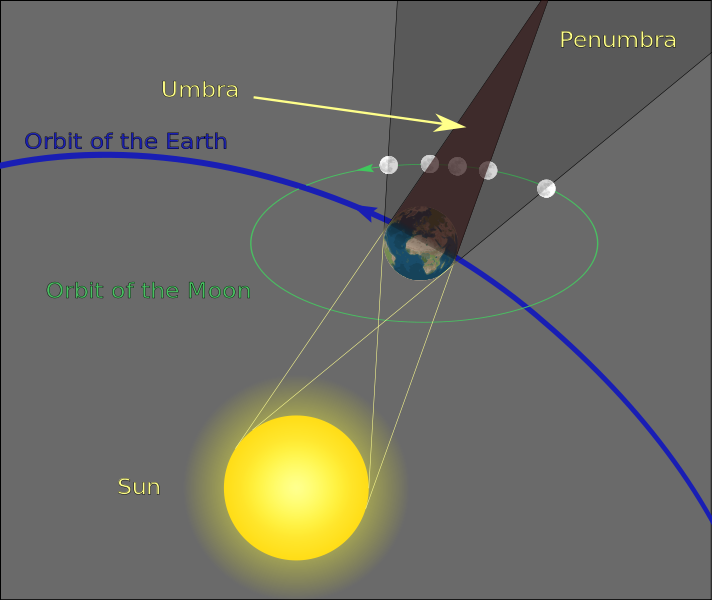

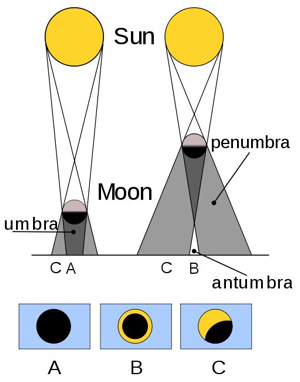

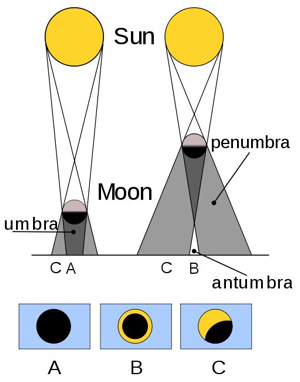

Contrasting a total solar eclipse (A) with an annular eclipse (B) Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other proposed dates include June 28, 1451 and June 18, 1536. But the total solar eclipse of 1451 June 28 did not swing as close to Victor as did the one on 1142 August 22. The path of 1536 June 18 eclipse didn’t pass particularly close to Victor either, and moreover, it came at the wrong time of day, and was an annular eclipse, rather than a total eclipse of the sun.

See the diagram at right to contrast a total solar eclipse with an annular eclipse. During a total solar eclipse, the new moon totally covers over the solar disk; during an annular eclipse, the new moon lies too far from Earth to completely cover over the sun, so a thin annulus – or ring – of sunshine circles the new moon silhouette.

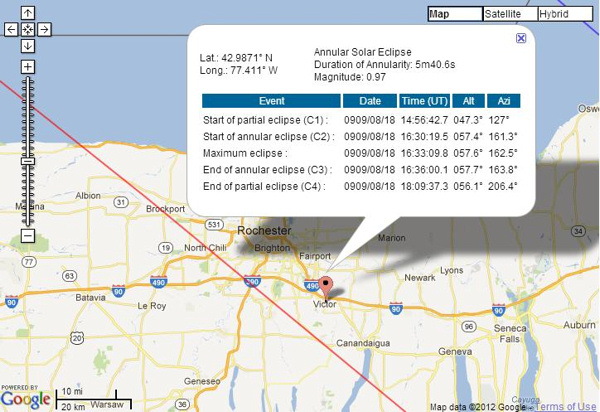

Could it have been an annular solar eclipse that convinced the Seneca to join the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy at Gonandaga (Victor, NY)? If so, the formation of Haudenosaunee (Five Nations) might go all the way back to the annular eclipse of August 18, 909. The middle of the eclipse path (in red) on the below chart almost exactly crosses Victor, NY!

Map showing Victor, NY, and August 909 eclipse path

Map Credit: NASA Eclipse Web Site

These web pages can help you search out eclipse history in more detail: Major Solar Eclipses Visible from New York, NY and Five Millennium Catalog of Solar Eclipses.

Eclipses are a great way to document history. But the real item of importance, as far as I’m concerned, is the acceptance of the Peacemaker and the democratic ideals of the Iroquois Confederacy.

Bottom line: Research suggests the total solar eclipse of August 22, 1142 coincided with the birth of the Iroquois (Five Nations) Confederacy, near modern-day Victor, New York.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2lvB4F5

Original Iroquois League was known as the Five Nations

My wife Alice regularly brings home the Indian Time news journal, a publication from the Akwesasne Mohawk Nation Territory in northern New York. It was with great interest that I came across an article titled Dating the Iroquois Confederacy by Bruce E. Johansen.

What really attracted my attention was that a total, or near total, solar eclipse marked the beginning of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, the oldest living democracy in North America and possibly on Earth. American democracy is said to have been modeled upon the democratic ideals of the Iroquois Confederacy, which originally consisted of five nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca). The sixth nation – the Tuscarora – joined the Iroquois Confederacy in the early eighteenth century (1701-1800).

Total solar eclipse of the sun on July 2, 2019

Map of the New York tribes before European arrival. Lavender indicates Iroquoian tribes. Orange indicates Algonquian tribes. Source: Smithsonian Institution

Iroquois, one of the historical figures of the Maisonneuve Monument, by Louis-Philippe Hébert, 1895, Place d’Armes, Montreal. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Bruce E. Johansen refers to the research done by Barbara A. Mann and Jerry L. Fields, which uses eclipse data as well as oral history to challenge the common notion that the Iroquois Confederacy or Iroquois League started in the fifteenth (1401-1500) or sixteenth (1501-1600) century. They state:

We know this much: During a ratification council held at Ganondagan (near modern-day Victor, New York) the sky darkened in a total, or near total, eclipse. The time of day was afternoon, as Councils are held between noon and sunset. The time of year was either Second Hoeing (early July) or Green Corn (late August to early September). Thus, we must look for an eclipse path that would totally cover Ganondagan between July and September, in mid-afternoon.

Mann and Fields settled upon the total solar eclipse of August 22, 1142 as satisfying the stated criteria. Bruce E. Johansen even pinpoints where the ratification of the Iroquois League took place:

The ratification council convened at a site that is now a football field in Victor, New York. The site is called Gonandaga by the Seneca.

Traditional Iroquois Longhouse. Source: Wilber F. Gordy

I looked up the August 1142 total solar eclipse at the NASA Eclipse Web Site. You can see this map for yourself by clicking here.

Map showing Victor, NY, and August 1142 eclipse path

Map Credit: NASA Eclipse Web Site

For the fun of it, I zoomed into the August 1142 eclipse map until finding Victor, New York. Looking along the zoomed-in eclipse path above, you can see Victor a short way to the north of the northern limit of total solar eclipse path (in blue). Nonetheless, it would have been very close to a total solar eclipse at greatest eclipse. Rounding off to the nearest minute, the partial eclipse started at 19:29 Universal Time (2:29 p.m. Eastern Standard Time), maximum eclipse arrived at 20:40 UT (3:40 p.m. EST) and the partial eclipse ended at 21:45 UT (4:45 p.m. EST).

Contrasting a total solar eclipse (A) with an annular eclipse (B) Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other proposed dates include June 28, 1451 and June 18, 1536. But the total solar eclipse of 1451 June 28 did not swing as close to Victor as did the one on 1142 August 22. The path of 1536 June 18 eclipse didn’t pass particularly close to Victor either, and moreover, it came at the wrong time of day, and was an annular eclipse, rather than a total eclipse of the sun.

See the diagram at right to contrast a total solar eclipse with an annular eclipse. During a total solar eclipse, the new moon totally covers over the solar disk; during an annular eclipse, the new moon lies too far from Earth to completely cover over the sun, so a thin annulus – or ring – of sunshine circles the new moon silhouette.

Could it have been an annular solar eclipse that convinced the Seneca to join the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy at Gonandaga (Victor, NY)? If so, the formation of Haudenosaunee (Five Nations) might go all the way back to the annular eclipse of August 18, 909. The middle of the eclipse path (in red) on the below chart almost exactly crosses Victor, NY!

Map showing Victor, NY, and August 909 eclipse path

Map Credit: NASA Eclipse Web Site

These web pages can help you search out eclipse history in more detail: Major Solar Eclipses Visible from New York, NY and Five Millennium Catalog of Solar Eclipses.

Eclipses are a great way to document history. But the real item of importance, as far as I’m concerned, is the acceptance of the Peacemaker and the democratic ideals of the Iroquois Confederacy.

Bottom line: Research suggests the total solar eclipse of August 22, 1142 coincided with the birth of the Iroquois (Five Nations) Confederacy, near modern-day Victor, New York.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2lvB4F5