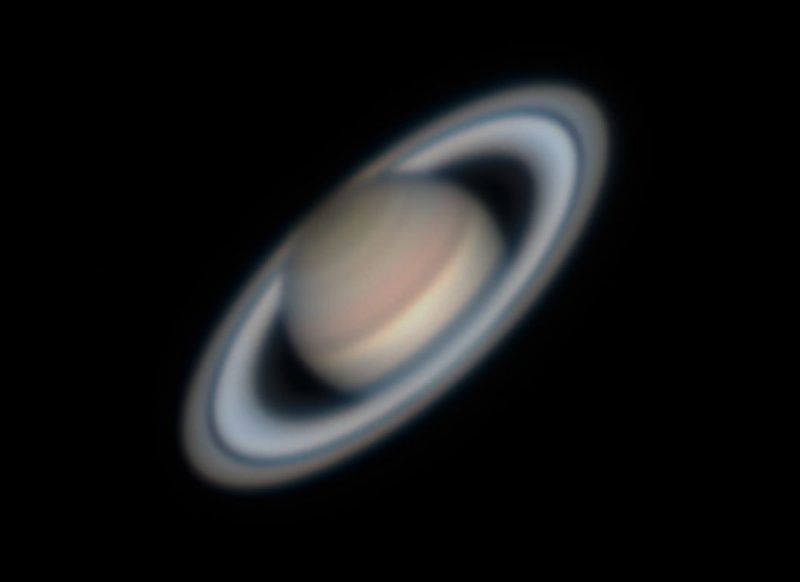

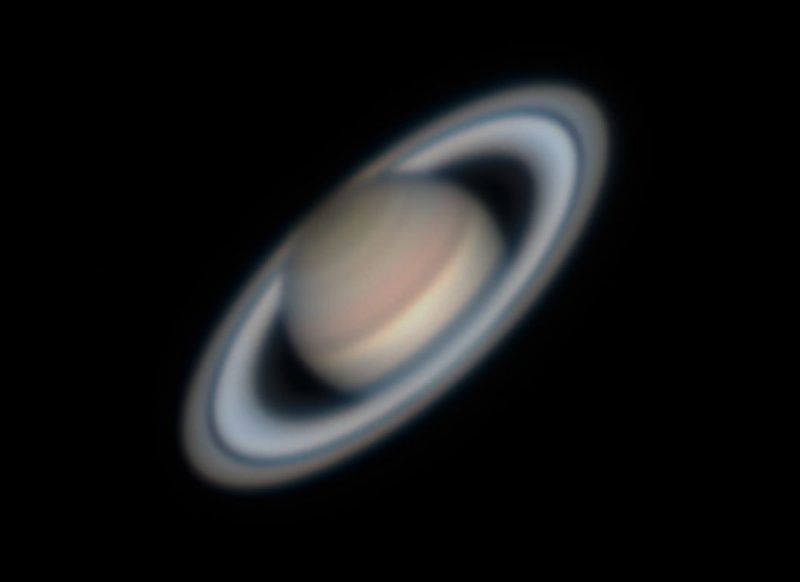

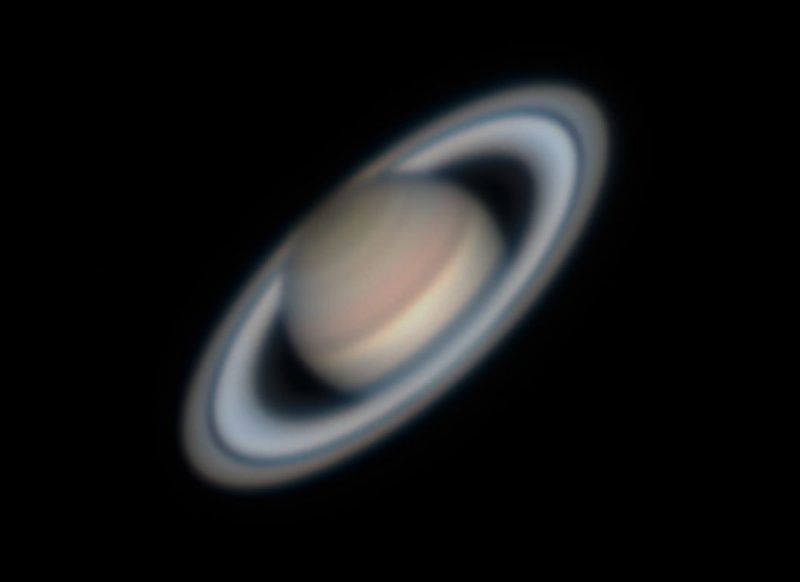

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Patrick Prokop in Savannah, Georgia, caught this glorious image of golden Saturn on July 3, 2019. He wrote: “Saturn is at its best viewing for the year as it reaches opposition on July 9. That is the night that the Earth is between the sun and Saturn … Earth is about 93.2 million miles from the sun now while Saturn will be 841.4 million miles from us then. I took this picture shortly after midnight July 3 from my backyard. On July 9 it will be roughly a half million miles closer than it was at the time of this picture.” Thank you, Patrick!

There has been a lot of talk in recent weeks about exciting times for observing Jupiter and Saturn. That’s because both reach opposition in this northern summer of 2019, Jupiter on June 10 and Saturn on July 9. In fact, opposition happens yearly for both of these outer planets. It’s an event that marks the middle of the best time of year to view these planets. So … what is opposition?

Imagine the solar system, with the planets running around in their orbits. Let’s keep things simple and just imagine the sun in the middle with the Earth a little way out, Jupiter about five times farther, and then Saturn about twice as far away from the sun as Jupiter. We’ll assume we’re watching from a spot high above Earth’s North Pole, which would mean that everything is moving counterclockwise.

Now, hit pause. Where are the planets? Maybe Earth is off to the left of the sun, and maybe Jupiter and Saturn are to the right. From this view, it doesn’t really matter what the line from the sun to Earth is like; after all, there’s always a straight line between any two objects in space. But what’s the Earth-sun line doing with respect to, say, Saturn? For most of every year, the Earth-sun line would need to jog off in a different direction to get to Saturn.

If we let our imaginary solar system run a little longer, though, the line will straighten. Nearly every year, there will be a point where it’s perfectly straight – sun, Earth, Saturn – as in the illustration below. Earth will be passing between Saturn and the sun in our planet’s yearly orbit.

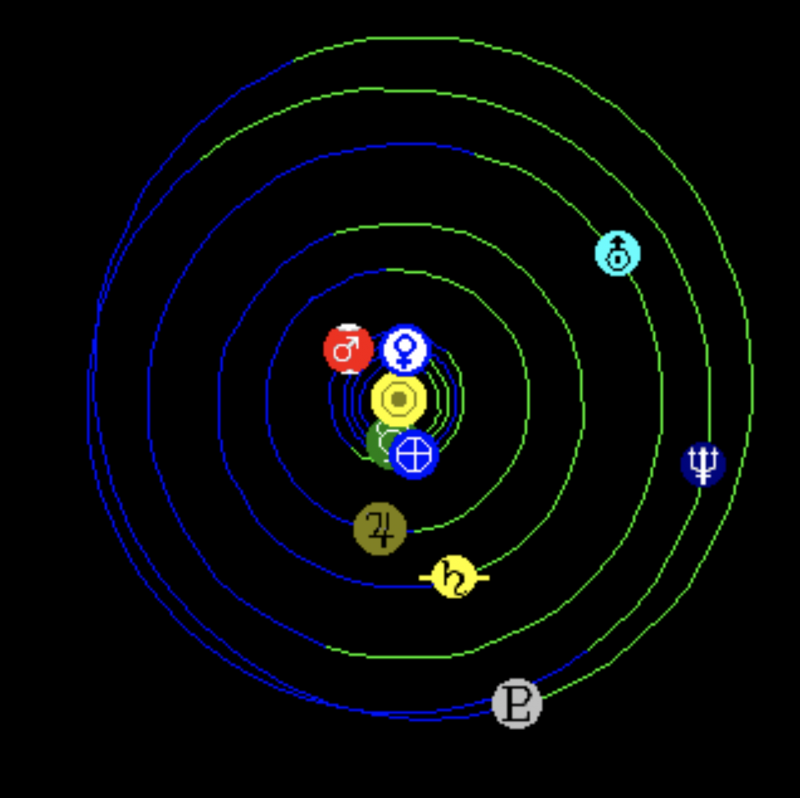

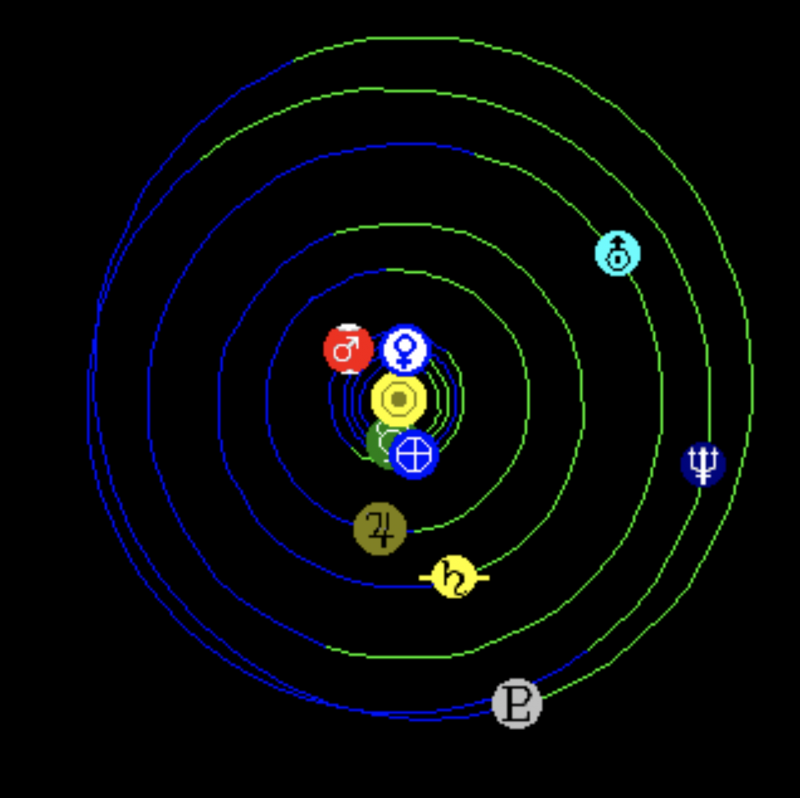

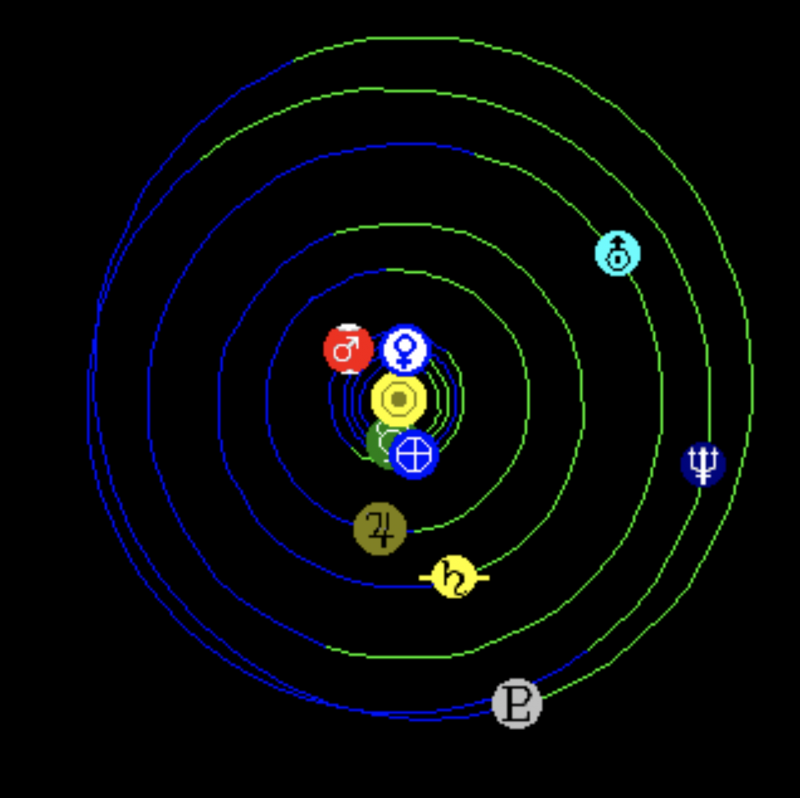

View larger. | An illustration of the solar system – as viewed from Earthly north – on the day of Saturn’s opposition. Earth is passing between Saturn and the sun. In this illustration, the yellow ball in the center (with the central dot) is the sun. Jupiter is brown; Saturn is yellow; Earth is blue. Everything is moving counterclockwise. Note that Earth passed between Jupiter at the sun last month, so that we are now racing ahead of this planet. Jupiter’s 2019 opposition was June 10. Earth passes between Saturn and the sun this week, on July 9. Diagram not to scale. Via Fourmilab.

What about the view in Earth’s sky? Since – at opposition – Earth is in the middle of a line between an outer planet and the sun, we see the sun at one end of our sky and the opposition planet in the opposite direction. It’s as if you’re standing directly between two friends as you chat in the supermarket, and you need to turn your head halfway around to see one, and then the other. At opposition, the sun is on the opposite side of the sky from the outer planet; when the sun sets in the west, the planet is rising in the east. As the planet drops below the horizon, the sun pops above it again – opposite.

To be technical, opposition for an outer planet happens when the sun and that planet are exactly 180 degrees apart in the sky. The word comes to English from a Latin root, meaning to set against.

Consider that Venus and Mercury can never be at opposition as seen from Earth. Their orbits are closer to the sun than Earth’s, so they can never appear opposite the sun in our sky. You will never see Venus in the east, for example, when the sun is setting in the west. These inner planets always stay near the sun, no more than 47 degrees from the sun for Venus, or 28 degrees for Mercury, in our sky.

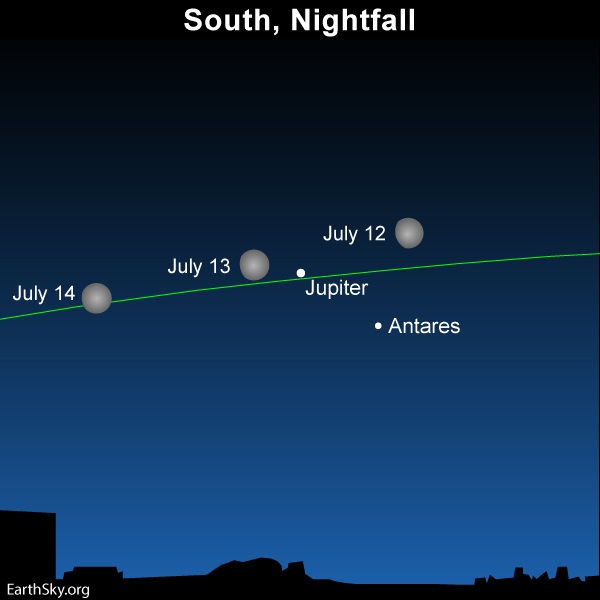

Oppositions can only happen for objects that are father from the sun than Earth is. We see oppositions for Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune about every year. They happen as Earth, in its much-faster orbit, passes between these outer worlds and the sun. We see oppositions of the planet Mars, too, but Martian oppositions happen about every 27 months because Earth and Mars are so relatively close together in orbit around the sun; their orbits, and speeds in orbit, are more similar. Since everything in space is always moving, oppositions of outer planets happen over and over, as Earth catches up and then passes the planet, on our inner track around the sun. As far as the bright planets go, the next opposition is never too far away:

Mars was at opposition on July 27, 2018, and will be again on October 13, 2020, and December 8, 2022.

Jupiter was at opposition on June 10, 2019, and will be again on July 14, 2020, August 19, 2021, and September 26, 2022.

Saturn will be at opposition on July 9, 2019, and then again on July 20, 2020, August 2, 2021, and August 14, 2022.

View full-sized image. | Project Nightflight released this photo on September 2, 2018. It shows Mars in mid-August, a couple of weeks after its late July opposition in 2018. See how bright it is? Planets at opposition are bright partly because it’s around then that they are closest to us. Also, at opposition, an outer planet’s fully lighted face, or day side, faces us most directly. Photo via the Project Nightflight team. Read more about this image.

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Eli Frisbie in Eagle Mountain, Utah, created this composite image from photos gathered on June 6, 2019, just a few days before Jupiter’s opposition. He wrote: “The Milky Way shines over a country road … The bright ‘star’ to the right of the Milky Way is the planet Jupiter. The slightly less-bright star to the upper left is the planet Saturn.” Thank you, Eli!

Why are planets at opposition so interesting to sky-watchers?

As mentioned, because they’re opposite the sun, planets at opposition rise when the sun sets and can be found somewhere in the sky throughout the night.

Secondly, planets at opposition tend to be near their closest point to Earth in orbit. Due to the non-circular shape of planetary orbits, the exact closest point might be different by a day or two, as Jupiter’s was this past June. Jupiter’s opposition was June 10, and its exact closest point was June 12. Still, for many weeks around opposition – between the time we pass between an outer planet and the sun – the outer planet is generally closest to Earth. At such a time, the planet is brightest, and more detail can be seen through telescopes.

And here’s another interesting aspect of opposition. Since the sun and outer planet are directly opposite each other in Earth’s sky, we see that far-off planet’s fully lighted daytime side. Fully-lit planets appear brighter to us than less-fully-lit planets. If you’re saying to yourself that this sounds a lot like the moon, you’re right! After all, what’s a full moon if not the moon at opposition? During the moon’s full phase, it’s directly opposite the sun in the sky, fully illuminated, and at its brightest for that orbit. As it moves through the rest of its orbit, the sun-Earth-moon line bends and gives us what we see from Earth as the moon’s phases.

Like so much in life, opposition is all about point of view. We’ve been talking about the view from Earth. What if we flip it around? When an outer planet – let’s say Jupiter – is at opposition for us, Earth is at inferior conjunction as seen from that planet. In other words, at the moment for us on Earth, observers on Jupiter would see Earth passing between their world and the sun. The Earth and the sun would be in the same side of Jupiter’s sky, hidden in the sun’s glare, except to skilled observers using special equipment. Consider also that the line from the sun to Jupiter passes through the Earth, which means Earth passes directly between the sun and Jupiter. Maybe one day, a visitor to Jupiter will see Earth transit the sun as seen from Jupiter. That is, they’ll see Earth’s darkened nighttime side, and all of humanity, cross the face of the sun from a half billion miles away.

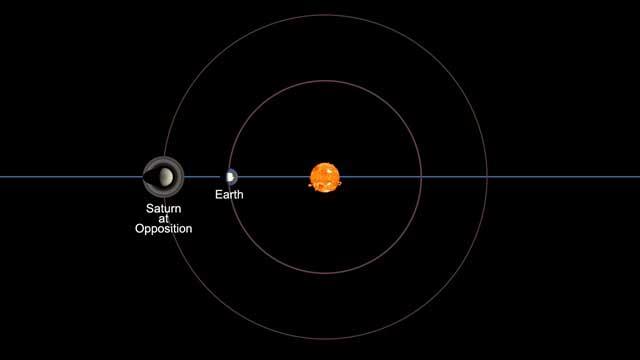

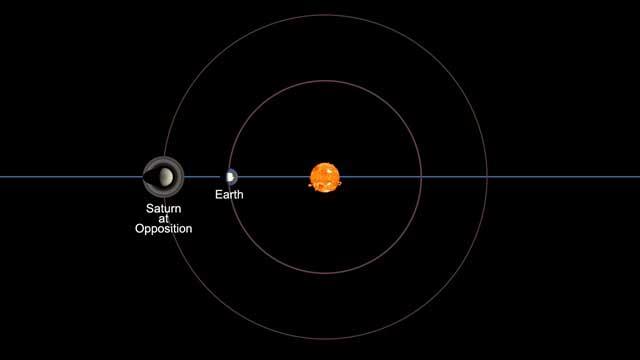

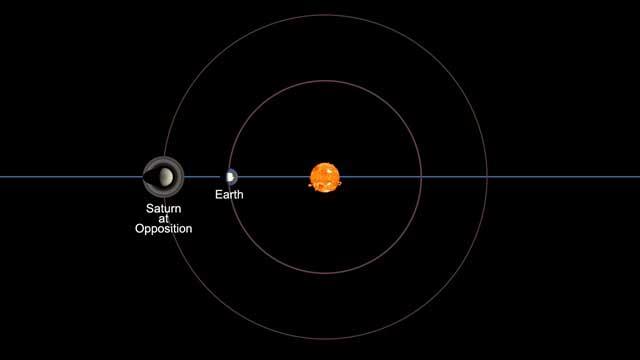

Another artist’s concept of Saturn in opposition to the sun. Distances not to scale! Image via NASA.

Bottom Line: In astronomy, we say an outer planet is at opposition when it’s directly opposite the sun, rising at sunset. Opposition marks the middle of the best time of year to see an outer planet.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2L8UMSJ

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Patrick Prokop in Savannah, Georgia, caught this glorious image of golden Saturn on July 3, 2019. He wrote: “Saturn is at its best viewing for the year as it reaches opposition on July 9. That is the night that the Earth is between the sun and Saturn … Earth is about 93.2 million miles from the sun now while Saturn will be 841.4 million miles from us then. I took this picture shortly after midnight July 3 from my backyard. On July 9 it will be roughly a half million miles closer than it was at the time of this picture.” Thank you, Patrick!

There has been a lot of talk in recent weeks about exciting times for observing Jupiter and Saturn. That’s because both reach opposition in this northern summer of 2019, Jupiter on June 10 and Saturn on July 9. In fact, opposition happens yearly for both of these outer planets. It’s an event that marks the middle of the best time of year to view these planets. So … what is opposition?

Imagine the solar system, with the planets running around in their orbits. Let’s keep things simple and just imagine the sun in the middle with the Earth a little way out, Jupiter about five times farther, and then Saturn about twice as far away from the sun as Jupiter. We’ll assume we’re watching from a spot high above Earth’s North Pole, which would mean that everything is moving counterclockwise.

Now, hit pause. Where are the planets? Maybe Earth is off to the left of the sun, and maybe Jupiter and Saturn are to the right. From this view, it doesn’t really matter what the line from the sun to Earth is like; after all, there’s always a straight line between any two objects in space. But what’s the Earth-sun line doing with respect to, say, Saturn? For most of every year, the Earth-sun line would need to jog off in a different direction to get to Saturn.

If we let our imaginary solar system run a little longer, though, the line will straighten. Nearly every year, there will be a point where it’s perfectly straight – sun, Earth, Saturn – as in the illustration below. Earth will be passing between Saturn and the sun in our planet’s yearly orbit.

View larger. | An illustration of the solar system – as viewed from Earthly north – on the day of Saturn’s opposition. Earth is passing between Saturn and the sun. In this illustration, the yellow ball in the center (with the central dot) is the sun. Jupiter is brown; Saturn is yellow; Earth is blue. Everything is moving counterclockwise. Note that Earth passed between Jupiter at the sun last month, so that we are now racing ahead of this planet. Jupiter’s 2019 opposition was June 10. Earth passes between Saturn and the sun this week, on July 9. Diagram not to scale. Via Fourmilab.

What about the view in Earth’s sky? Since – at opposition – Earth is in the middle of a line between an outer planet and the sun, we see the sun at one end of our sky and the opposition planet in the opposite direction. It’s as if you’re standing directly between two friends as you chat in the supermarket, and you need to turn your head halfway around to see one, and then the other. At opposition, the sun is on the opposite side of the sky from the outer planet; when the sun sets in the west, the planet is rising in the east. As the planet drops below the horizon, the sun pops above it again – opposite.

To be technical, opposition for an outer planet happens when the sun and that planet are exactly 180 degrees apart in the sky. The word comes to English from a Latin root, meaning to set against.

Consider that Venus and Mercury can never be at opposition as seen from Earth. Their orbits are closer to the sun than Earth’s, so they can never appear opposite the sun in our sky. You will never see Venus in the east, for example, when the sun is setting in the west. These inner planets always stay near the sun, no more than 47 degrees from the sun for Venus, or 28 degrees for Mercury, in our sky.

Oppositions can only happen for objects that are father from the sun than Earth is. We see oppositions for Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune about every year. They happen as Earth, in its much-faster orbit, passes between these outer worlds and the sun. We see oppositions of the planet Mars, too, but Martian oppositions happen about every 27 months because Earth and Mars are so relatively close together in orbit around the sun; their orbits, and speeds in orbit, are more similar. Since everything in space is always moving, oppositions of outer planets happen over and over, as Earth catches up and then passes the planet, on our inner track around the sun. As far as the bright planets go, the next opposition is never too far away:

Mars was at opposition on July 27, 2018, and will be again on October 13, 2020, and December 8, 2022.

Jupiter was at opposition on June 10, 2019, and will be again on July 14, 2020, August 19, 2021, and September 26, 2022.

Saturn will be at opposition on July 9, 2019, and then again on July 20, 2020, August 2, 2021, and August 14, 2022.

View full-sized image. | Project Nightflight released this photo on September 2, 2018. It shows Mars in mid-August, a couple of weeks after its late July opposition in 2018. See how bright it is? Planets at opposition are bright partly because it’s around then that they are closest to us. Also, at opposition, an outer planet’s fully lighted face, or day side, faces us most directly. Photo via the Project Nightflight team. Read more about this image.

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Eli Frisbie in Eagle Mountain, Utah, created this composite image from photos gathered on June 6, 2019, just a few days before Jupiter’s opposition. He wrote: “The Milky Way shines over a country road … The bright ‘star’ to the right of the Milky Way is the planet Jupiter. The slightly less-bright star to the upper left is the planet Saturn.” Thank you, Eli!

Why are planets at opposition so interesting to sky-watchers?

As mentioned, because they’re opposite the sun, planets at opposition rise when the sun sets and can be found somewhere in the sky throughout the night.

Secondly, planets at opposition tend to be near their closest point to Earth in orbit. Due to the non-circular shape of planetary orbits, the exact closest point might be different by a day or two, as Jupiter’s was this past June. Jupiter’s opposition was June 10, and its exact closest point was June 12. Still, for many weeks around opposition – between the time we pass between an outer planet and the sun – the outer planet is generally closest to Earth. At such a time, the planet is brightest, and more detail can be seen through telescopes.

And here’s another interesting aspect of opposition. Since the sun and outer planet are directly opposite each other in Earth’s sky, we see that far-off planet’s fully lighted daytime side. Fully-lit planets appear brighter to us than less-fully-lit planets. If you’re saying to yourself that this sounds a lot like the moon, you’re right! After all, what’s a full moon if not the moon at opposition? During the moon’s full phase, it’s directly opposite the sun in the sky, fully illuminated, and at its brightest for that orbit. As it moves through the rest of its orbit, the sun-Earth-moon line bends and gives us what we see from Earth as the moon’s phases.

Like so much in life, opposition is all about point of view. We’ve been talking about the view from Earth. What if we flip it around? When an outer planet – let’s say Jupiter – is at opposition for us, Earth is at inferior conjunction as seen from that planet. In other words, at the moment for us on Earth, observers on Jupiter would see Earth passing between their world and the sun. The Earth and the sun would be in the same side of Jupiter’s sky, hidden in the sun’s glare, except to skilled observers using special equipment. Consider also that the line from the sun to Jupiter passes through the Earth, which means Earth passes directly between the sun and Jupiter. Maybe one day, a visitor to Jupiter will see Earth transit the sun as seen from Jupiter. That is, they’ll see Earth’s darkened nighttime side, and all of humanity, cross the face of the sun from a half billion miles away.

Another artist’s concept of Saturn in opposition to the sun. Distances not to scale! Image via NASA.

Bottom Line: In astronomy, we say an outer planet is at opposition when it’s directly opposite the sun, rising at sunset. Opposition marks the middle of the best time of year to see an outer planet.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2L8UMSJ