Artist’s concept comparing sunsets as viewed from Earth and from each of the 2 newly discovered planets orbiting Teegarden’s Star. Image via PHL @ UPR Arecibo.

Astronomers have confirmed over 4,000 exoplanets – planets orbiting other stars – so far, and among these are a growing number of Earth-sized worlds. Now, two more such planets have been found, orbiting one of the nearest stars to our own solar system, just 12.5 light-years away. These new planets – orbiting Teegarden’s Star – might also be potentially habitable, since both are in their star’s habitable zone.

An international team of astronomers from the University of Göttingen announced the discovery on June 18, 2019. Their peer-reviewed results were accepted in Astronomy & Astrophysics on May 14, 2019.

At 12.5 light-years away, the planets are some of the closest found so far. Astronomers have labeled them Teegarden b and c. They are now the joint fourth-nearest habitable zone exoplanets to Earth known. The Teegarden star system itself is the 24th closest to ours. According to lead author Mathias Zechmeister:

The two planets resemble the inner planets of our solar system. They are only slightly heavier than Earth and are located in the so-called habitable zone, where water can be present in liquid form.

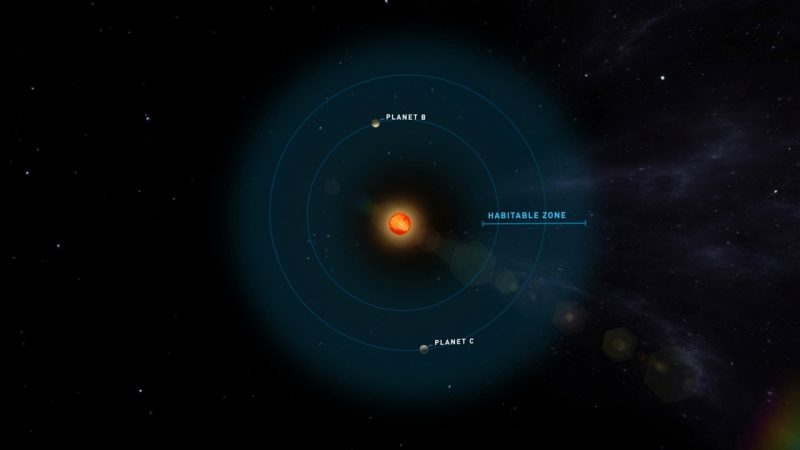

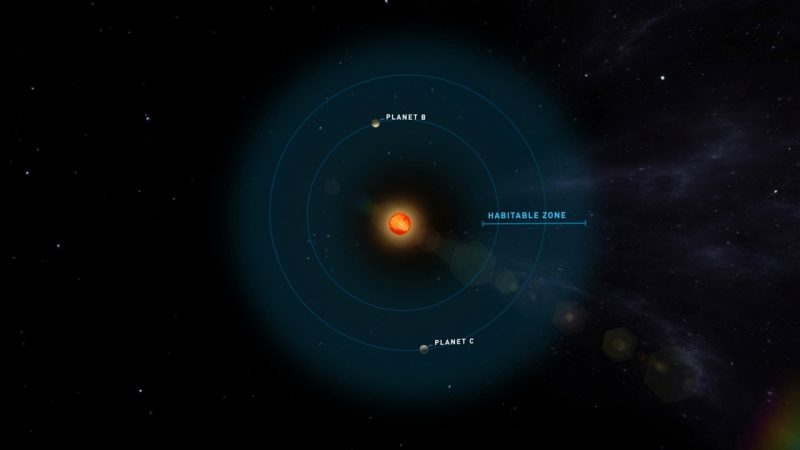

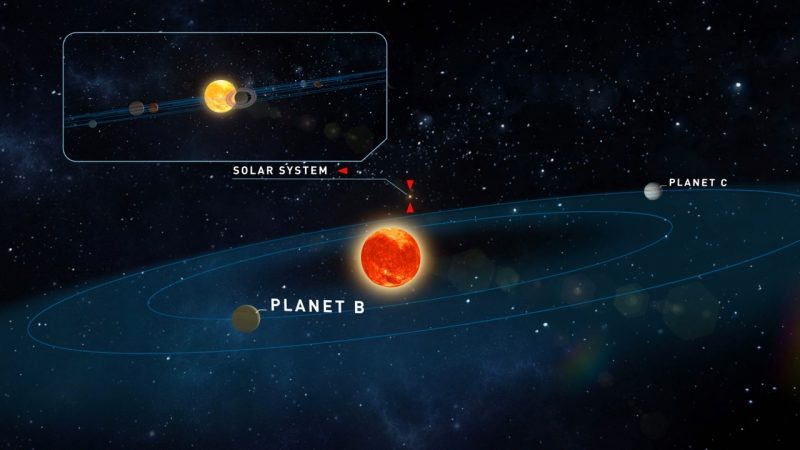

The 2 planets discovered orbiting Teegarden’s Star both reside in the habitable zone, where temperatures would allow liquid water to exist. Image via University of Göttingen, Institute for Astrophysics.

Teegarden’s Star is one of the smallest stars known, some 10 times less massive than our sun. It is also much cooler, at about 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,700 degrees Celsius). Because it is so relatively cool, and thus relatively dim, Teegarden’s Star wasn’t known to astronomers until 2003, despite being so close. The star is named for the discovery team leader, Bonnard J. Teegarden, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (now retired).

Teegarden’s Star is a small M-type red dwarf, and thus the habitable zone for this star is also much smaller than the one around our sun, for example. But, as it happens, both newly discovered planets orbit within this zone. That doesn’t necessarily mean there is life there, but it does show that the planets are potentially habitable, depending on other factors such as composition and atmosphere. Red dwarf stars are also notorious for emitting dangerous and powerful solar flares, which could even sometimes strip planets of their atmospheres.

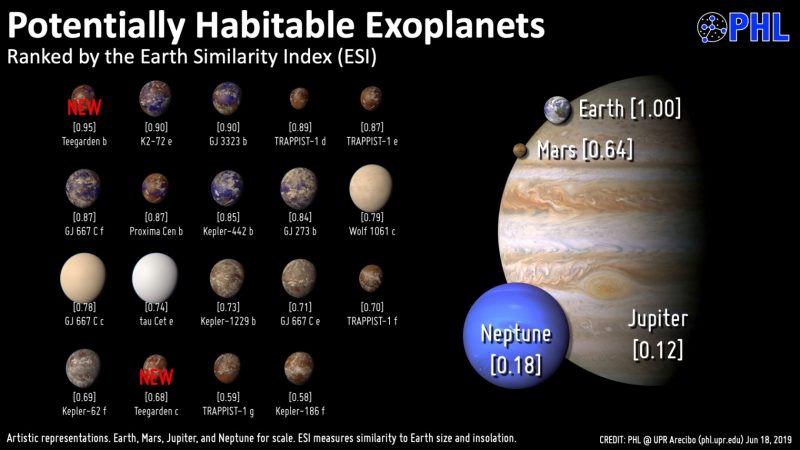

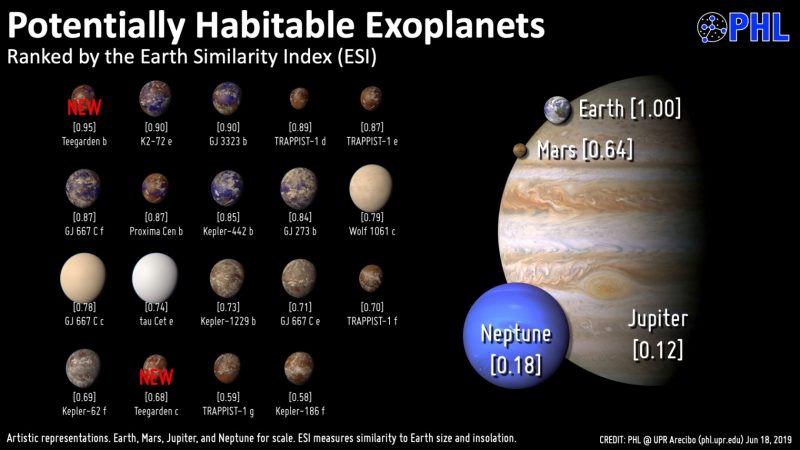

Teegarden b has been rated as “95% Earth-similar” on the Earth Similarity Index, which is based on Abel Mendez’s analysis, conducted at the Planetary Habitability Laboratory, managed by the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. The Earth Similarity Index is an approximation, based on known factors about a planet, but is not definitive. It serves as a guide as to how Earth-like a planet might be, but there are many factors that have to be taken into consideration. Even if the planet has water, its habitability also depends on temperature and the composition of both the planet itself and its atmosphere. As an example, this recent EarthSky story talked about potential toxic gases in a planet’s atmosphere.

According to the Earth Similarity Index, Teegarden b has a 60 percent chance of having a temperate surface environment, temperatures between 32 degrees to 122 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees to 50 degrees Celsius). If its atmosphere is similar to Earth’s, the surface temperature should be closer to 82 degrees F (28 degrees C). Teegarden c, farther from the star, has a 68 percent Earth Similarity Index, with only a 3 percent chance of having a warm surface temperature. The temperature is estimated to be -52 F (-47 degrees C), if the atmosphere is more similar to that of Mars. Both planets have now been added to the Planetary Habitability Laboratory’s Habitable Exoplanets Catalog.

Teegarden b and Teegarden c have now been added to the Habitable Exoplanets Catalog at the Planetary Habitability Laboratory, using the Earth Similarity Index. Image via PHL @ UPR Arecibo.

As a bonus, the astronomers also think that there might be other planets in this system. As co-author Stefan Dreizler of the University of Göttingen noted:

Many stars are apparently surrounded by systems with several planets.

Teegarden’s Star is also the smallest star where astronomers have been able to directly measure the weight of a planet. According to Ansgar Reiners, also of the University of Göttingen:

This is a great success for the Carmenes project, which was specifically designed to search for planets around the lightest stars.

The astronomers also realized something else about the Teegarden’s Star planetary system: if you were there, you would be able to look back at our own solar system and see the planets transit in front of the sun. As Reiners said:

An inhabitant of the new planets would therefore have the opportunity to view the Earth using the transit method. The new planets are the 10th and 11th discovered by the team.

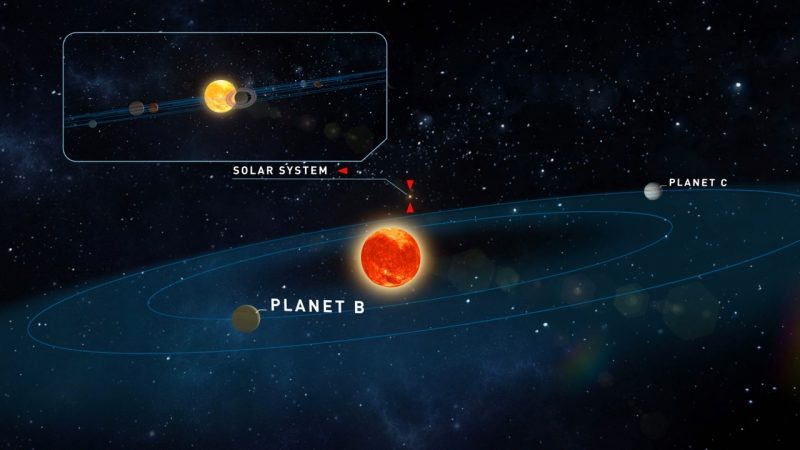

Artist’s concept of the 2 new planets orbiting Teegarden’s Star. From those planets, you could see the planets in our own solar system transiting (crossing) in front of the face of our sun. Image via University of Göttingen, Institute for Astrophysics.

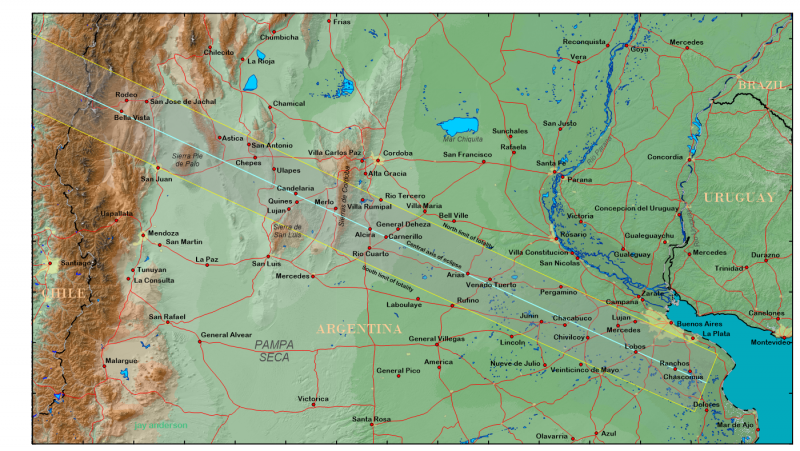

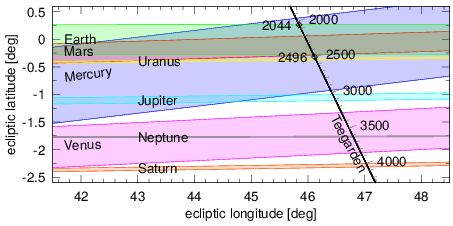

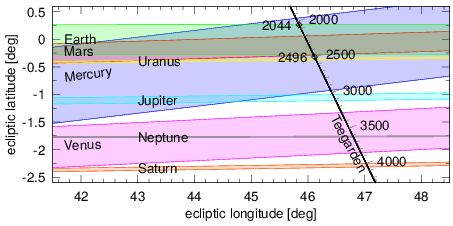

Graph depicting transits of planets in our solar system as seen from Teegarden’s Star. Image via University of Göttingen, Institute for Astrophysics.

This is how many exoplanets have been discovered so far, watching them transit in front of their stars, briefly blocking out some of the light coming from the star. If there were any alien astronomers at Teegarden’s star, they would be able to view the similar transits that the planets in our own solar system would make as they passed in front of the sun.

The two planets for Teegarden’s Star constitute an exciting discovery, even if we don’t fully know yet what the conditions on the planets are like. Their discovery shows, again, that smaller rocky planets like Earth are common in the galaxy (and probably the universe). This includes ones that are in the habitable zone of their stars. In our solar system, Earth is smack in the habitable zone, while Venus and Mars are near the inner and outer edges. There must be many more such planets out there, waiting to be found. How long will it be before we find one that is not only habitable, but actually inhabited with some form of life? That is still hard to tell at this point, but each discovery brings us closer to that moment.

Bottom line: The Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting Teegarden’s Star are two of the closest yet found, and at least one of them may be one of the most potentially habitable discovered so far.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2YsPYdE

Artist’s concept comparing sunsets as viewed from Earth and from each of the 2 newly discovered planets orbiting Teegarden’s Star. Image via PHL @ UPR Arecibo.

Astronomers have confirmed over 4,000 exoplanets – planets orbiting other stars – so far, and among these are a growing number of Earth-sized worlds. Now, two more such planets have been found, orbiting one of the nearest stars to our own solar system, just 12.5 light-years away. These new planets – orbiting Teegarden’s Star – might also be potentially habitable, since both are in their star’s habitable zone.

An international team of astronomers from the University of Göttingen announced the discovery on June 18, 2019. Their peer-reviewed results were accepted in Astronomy & Astrophysics on May 14, 2019.

At 12.5 light-years away, the planets are some of the closest found so far. Astronomers have labeled them Teegarden b and c. They are now the joint fourth-nearest habitable zone exoplanets to Earth known. The Teegarden star system itself is the 24th closest to ours. According to lead author Mathias Zechmeister:

The two planets resemble the inner planets of our solar system. They are only slightly heavier than Earth and are located in the so-called habitable zone, where water can be present in liquid form.

The 2 planets discovered orbiting Teegarden’s Star both reside in the habitable zone, where temperatures would allow liquid water to exist. Image via University of Göttingen, Institute for Astrophysics.

Teegarden’s Star is one of the smallest stars known, some 10 times less massive than our sun. It is also much cooler, at about 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit (2,700 degrees Celsius). Because it is so relatively cool, and thus relatively dim, Teegarden’s Star wasn’t known to astronomers until 2003, despite being so close. The star is named for the discovery team leader, Bonnard J. Teegarden, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (now retired).

Teegarden’s Star is a small M-type red dwarf, and thus the habitable zone for this star is also much smaller than the one around our sun, for example. But, as it happens, both newly discovered planets orbit within this zone. That doesn’t necessarily mean there is life there, but it does show that the planets are potentially habitable, depending on other factors such as composition and atmosphere. Red dwarf stars are also notorious for emitting dangerous and powerful solar flares, which could even sometimes strip planets of their atmospheres.

Teegarden b has been rated as “95% Earth-similar” on the Earth Similarity Index, which is based on Abel Mendez’s analysis, conducted at the Planetary Habitability Laboratory, managed by the University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. The Earth Similarity Index is an approximation, based on known factors about a planet, but is not definitive. It serves as a guide as to how Earth-like a planet might be, but there are many factors that have to be taken into consideration. Even if the planet has water, its habitability also depends on temperature and the composition of both the planet itself and its atmosphere. As an example, this recent EarthSky story talked about potential toxic gases in a planet’s atmosphere.

According to the Earth Similarity Index, Teegarden b has a 60 percent chance of having a temperate surface environment, temperatures between 32 degrees to 122 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees to 50 degrees Celsius). If its atmosphere is similar to Earth’s, the surface temperature should be closer to 82 degrees F (28 degrees C). Teegarden c, farther from the star, has a 68 percent Earth Similarity Index, with only a 3 percent chance of having a warm surface temperature. The temperature is estimated to be -52 F (-47 degrees C), if the atmosphere is more similar to that of Mars. Both planets have now been added to the Planetary Habitability Laboratory’s Habitable Exoplanets Catalog.

Teegarden b and Teegarden c have now been added to the Habitable Exoplanets Catalog at the Planetary Habitability Laboratory, using the Earth Similarity Index. Image via PHL @ UPR Arecibo.

As a bonus, the astronomers also think that there might be other planets in this system. As co-author Stefan Dreizler of the University of Göttingen noted:

Many stars are apparently surrounded by systems with several planets.

Teegarden’s Star is also the smallest star where astronomers have been able to directly measure the weight of a planet. According to Ansgar Reiners, also of the University of Göttingen:

This is a great success for the Carmenes project, which was specifically designed to search for planets around the lightest stars.

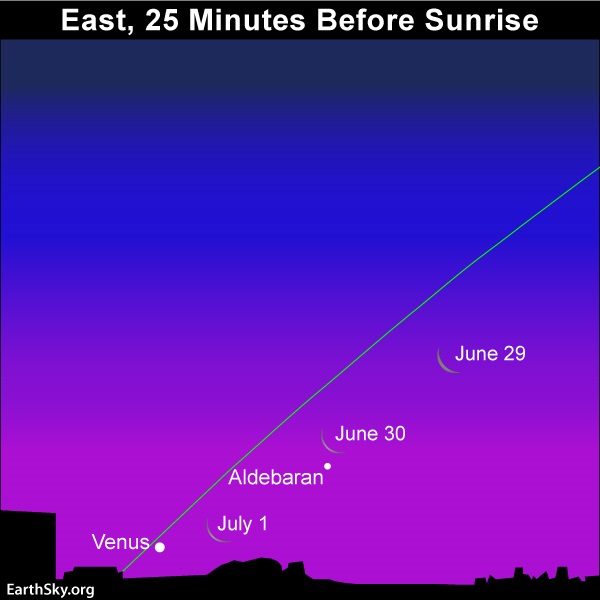

The astronomers also realized something else about the Teegarden’s Star planetary system: if you were there, you would be able to look back at our own solar system and see the planets transit in front of the sun. As Reiners said:

An inhabitant of the new planets would therefore have the opportunity to view the Earth using the transit method. The new planets are the 10th and 11th discovered by the team.

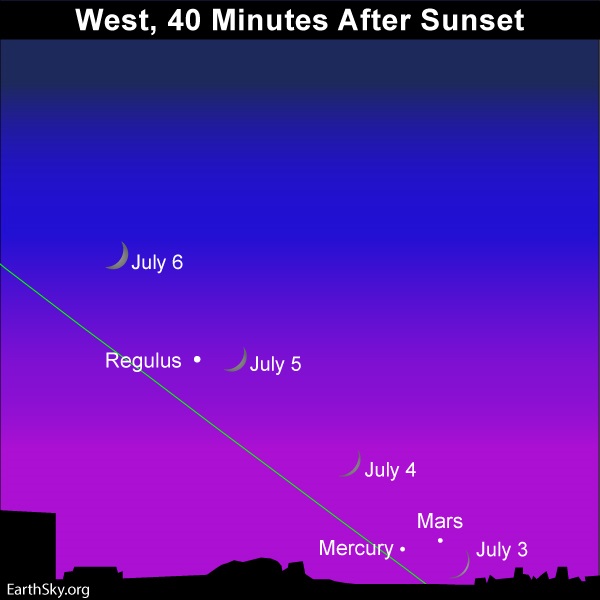

Artist’s concept of the 2 new planets orbiting Teegarden’s Star. From those planets, you could see the planets in our own solar system transiting (crossing) in front of the face of our sun. Image via University of Göttingen, Institute for Astrophysics.

Graph depicting transits of planets in our solar system as seen from Teegarden’s Star. Image via University of Göttingen, Institute for Astrophysics.

This is how many exoplanets have been discovered so far, watching them transit in front of their stars, briefly blocking out some of the light coming from the star. If there were any alien astronomers at Teegarden’s star, they would be able to view the similar transits that the planets in our own solar system would make as they passed in front of the sun.

The two planets for Teegarden’s Star constitute an exciting discovery, even if we don’t fully know yet what the conditions on the planets are like. Their discovery shows, again, that smaller rocky planets like Earth are common in the galaxy (and probably the universe). This includes ones that are in the habitable zone of their stars. In our solar system, Earth is smack in the habitable zone, while Venus and Mars are near the inner and outer edges. There must be many more such planets out there, waiting to be found. How long will it be before we find one that is not only habitable, but actually inhabited with some form of life? That is still hard to tell at this point, but each discovery brings us closer to that moment.

Bottom line: The Earth-sized exoplanets orbiting Teegarden’s Star are two of the closest yet found, and at least one of them may be one of the most potentially habitable discovered so far.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2YsPYdE