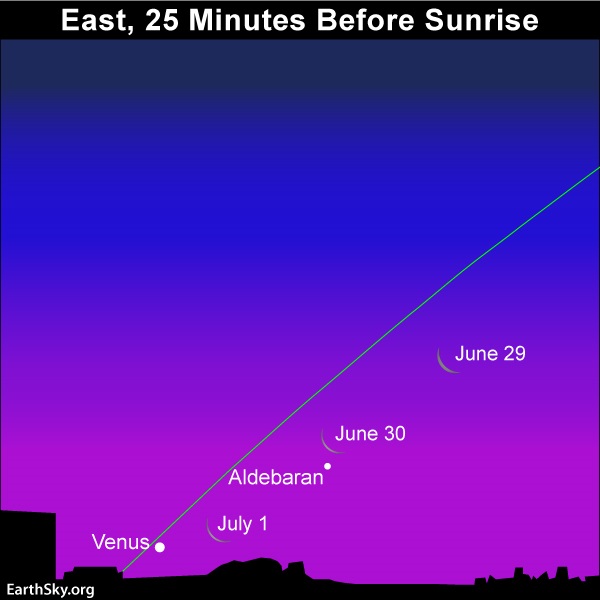

A 1929 image of fallen trees at Tunguska in Siberia. It wasn’t until 1927 that Russian scientists – led by Leonid Kulik – were finally able to get to the scene. Today, a global asteroid-awareness campaign (#WorldAsteroidDay) is held every June 30, the anniversary of the Tunguska event. Photo via the Soviet Academy of Science/Wikimedia Commons.

June 30, 1908 In a remote part of Russia, a fireball was seen streaking across the daytime sky. Within moments, something exploded in the atmosphere above Siberia’s Podkamennaya Tunguska River in what is now Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia. This event – now widely known as the Tunguska event – is believed to have been caused by an incoming asteroid (or comet), which never actually struck Earth but instead exploded in the atmosphere, causing what is known as an air burst, three to six miles (5–10 kilometers) above Earth’s surface.

The explosion released enough energy to kill reindeer and flatten trees for many kilometers around the blast site. But no crater was ever found. At the time, it was difficult to reach this remote part of Siberia. It wasn’t until 1927 that Leonid Kulik led the first Soviet research expedition to investigate the Tunguska event. He made a initial trip to the region, interviewed local witnesses and explored the region where the trees had been felled. He became convinced that they were all turned with their roots to the center. He did not find any meteorite fragments, and he did not find a meteorite crater.

Over the years, scientists and others concocted fabulous explanations for the Tunguska explosion. Some were pretty wild – such as the encounter of Earth with an alien spacecraft, or a mini-black-hole, or a particle of antimatter.

The truth is more ordinary. In all likelihood, a small icy comet or stony asteroid collided with Earth’s atmosphere on June 30, 1908. If it were an asteroid, it might have been about a third as big as a football field – moving at about 15 kilometers (10 miles) per second.

In 2019, new research – inspired by a workshop held at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley and sponsored by the NASA Planetary Defense Coordination Office – was published about the Tunguska event, in series of papers in a special issue of the journal Icarus. The theme of the workshop was reexamining the astronomical cold case of the 1908 Tunguska impact event.

Photo of an air burst, in this case from a U.S. Navy submarine-launched Tomamhawk cruise missile. An air burst from an incoming comet or asteroid is thought to have flattened trees in Siberia in 1908. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Vital clues to the Tunguska event appeared on February 15, 2013, when a smaller but still impressive meteor burst in the atmosphere near Chelyabinsk, Russia. NASA explained:

New evidence to help solve the mystery of Tunguska had arrived. This highly documented fireball created an opportunity for researchers to apply modern computer modeling techniques to explain what was seen, heard and felt.

The models were used with video observations of the fireball and maps of the damage on the ground to reconstruct the original size, motion and speed of the Chelyabinsk object. The resulting interpretation is that Chelyabinsk was most likely a stony asteroid the size of a five-story building that broke apart 15 miles above the ground. This generated a shock wave equivalent to a 550-kiloton explosion. The explosion’s shockwave blew out roughly a million windows and injured more than a thousand people. Fortunately, the force of the explosion was not enough to knock down trees or structures.

Per current understanding of the asteroid population, an object like the Chelyabinsk meteor can impact the Earth every 10 to 100 years on average.

Read more about the new research on the Tunguska event

In recent decades, astronomers have come to take the possibility of comet and asteroid impacts very seriously indeed. They now have regular observing programs to watch for Near-Earth Objects, as they’re called. They meet regularly to discuss what might happen if we did find an object on a collision course with Earth. And space scientists are planning missions to an asteroid, including Hera and __.

Lorien Wheeler – a researcher at NASA Ames Research Center, working on NASA’s Asteroid Threat Assessment Project – said:

Because there are so few observed cases, a lot of uncertainty remains about how large asteroids break up in the atmosphere and how much damage they could cause on the ground. However, recent advancements in computational models, along with analyses of the Chelyabinsk and other meteor events, are helping to improve our understanding of these factors so that we can better evaluate potential asteroid threats in the future.

Astronomer David Morrison, also at NASA Ames Research Center, commented:

Tunguska is the largest cosmic impact witnessed by modern humans. It also is characteristic of the sort of impact we are likely to have to protect against in the future.

Chelyabinsk meteor smoke trail, February 15, 2013. Image via Alex Alishevskikh., who caught it about a minute after the blast.

Bottom line: On June 30, 1908, an object from space exploded above Siberia. The explosion killed reindeer and flattened trees, in what has become known as the Tunguska event. Recent research shows that the object was most likely a stony asteroid the size of a five-story building that broke apart 15 miles above the ground.

Source: Icarus special papers on Tunguska

No, asteroid 2006 QV89 won’t strike Earth in September 2019

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2KOzXMd

A 1929 image of fallen trees at Tunguska in Siberia. It wasn’t until 1927 that Russian scientists – led by Leonid Kulik – were finally able to get to the scene. Today, a global asteroid-awareness campaign (#WorldAsteroidDay) is held every June 30, the anniversary of the Tunguska event. Photo via the Soviet Academy of Science/Wikimedia Commons.

June 30, 1908 In a remote part of Russia, a fireball was seen streaking across the daytime sky. Within moments, something exploded in the atmosphere above Siberia’s Podkamennaya Tunguska River in what is now Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia. This event – now widely known as the Tunguska event – is believed to have been caused by an incoming asteroid (or comet), which never actually struck Earth but instead exploded in the atmosphere, causing what is known as an air burst, three to six miles (5–10 kilometers) above Earth’s surface.

The explosion released enough energy to kill reindeer and flatten trees for many kilometers around the blast site. But no crater was ever found. At the time, it was difficult to reach this remote part of Siberia. It wasn’t until 1927 that Leonid Kulik led the first Soviet research expedition to investigate the Tunguska event. He made a initial trip to the region, interviewed local witnesses and explored the region where the trees had been felled. He became convinced that they were all turned with their roots to the center. He did not find any meteorite fragments, and he did not find a meteorite crater.

Over the years, scientists and others concocted fabulous explanations for the Tunguska explosion. Some were pretty wild – such as the encounter of Earth with an alien spacecraft, or a mini-black-hole, or a particle of antimatter.

The truth is more ordinary. In all likelihood, a small icy comet or stony asteroid collided with Earth’s atmosphere on June 30, 1908. If it were an asteroid, it might have been about a third as big as a football field – moving at about 15 kilometers (10 miles) per second.

In 2019, new research – inspired by a workshop held at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Silicon Valley and sponsored by the NASA Planetary Defense Coordination Office – was published about the Tunguska event, in series of papers in a special issue of the journal Icarus. The theme of the workshop was reexamining the astronomical cold case of the 1908 Tunguska impact event.

Photo of an air burst, in this case from a U.S. Navy submarine-launched Tomamhawk cruise missile. An air burst from an incoming comet or asteroid is thought to have flattened trees in Siberia in 1908. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Vital clues to the Tunguska event appeared on February 15, 2013, when a smaller but still impressive meteor burst in the atmosphere near Chelyabinsk, Russia. NASA explained:

New evidence to help solve the mystery of Tunguska had arrived. This highly documented fireball created an opportunity for researchers to apply modern computer modeling techniques to explain what was seen, heard and felt.

The models were used with video observations of the fireball and maps of the damage on the ground to reconstruct the original size, motion and speed of the Chelyabinsk object. The resulting interpretation is that Chelyabinsk was most likely a stony asteroid the size of a five-story building that broke apart 15 miles above the ground. This generated a shock wave equivalent to a 550-kiloton explosion. The explosion’s shockwave blew out roughly a million windows and injured more than a thousand people. Fortunately, the force of the explosion was not enough to knock down trees or structures.

Per current understanding of the asteroid population, an object like the Chelyabinsk meteor can impact the Earth every 10 to 100 years on average.

Read more about the new research on the Tunguska event

In recent decades, astronomers have come to take the possibility of comet and asteroid impacts very seriously indeed. They now have regular observing programs to watch for Near-Earth Objects, as they’re called. They meet regularly to discuss what might happen if we did find an object on a collision course with Earth. And space scientists are planning missions to an asteroid, including Hera and __.

Lorien Wheeler – a researcher at NASA Ames Research Center, working on NASA’s Asteroid Threat Assessment Project – said:

Because there are so few observed cases, a lot of uncertainty remains about how large asteroids break up in the atmosphere and how much damage they could cause on the ground. However, recent advancements in computational models, along with analyses of the Chelyabinsk and other meteor events, are helping to improve our understanding of these factors so that we can better evaluate potential asteroid threats in the future.

Astronomer David Morrison, also at NASA Ames Research Center, commented:

Tunguska is the largest cosmic impact witnessed by modern humans. It also is characteristic of the sort of impact we are likely to have to protect against in the future.

Chelyabinsk meteor smoke trail, February 15, 2013. Image via Alex Alishevskikh., who caught it about a minute after the blast.

Bottom line: On June 30, 1908, an object from space exploded above Siberia. The explosion killed reindeer and flattened trees, in what has become known as the Tunguska event. Recent research shows that the object was most likely a stony asteroid the size of a five-story building that broke apart 15 miles above the ground.

Source: Icarus special papers on Tunguska

No, asteroid 2006 QV89 won’t strike Earth in September 2019

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2KOzXMd