Example of a conjunction involving Venus and the Pleiades cluster, via Tom Wildoner at LeisurelyScientist.com.

Occasionally two or more objects meet up with each other in our sky. Astronomers use the word conjunction to describe these meetings. Technically speaking, objects are said to be in conjunction in that instant when they have the same right ascension on our sky’s dome. Practically speaking, objects in conjunction will likely be visible near each other for some days.

The word conjunction comes from Latin, meaning to join together. Maybe you remember the old Conjunction Junction cartoons from the 1970s. In language, conjunctions relate to clauses brought together in sentences. In astronomy, conjunctions relate to two or more objects brought together in the sky.

An astronomical conjunction describes a few different types of meetings. The first two types we’re describing here – inferior and superior conjunctions – involve the sun and thus can’t be seen.

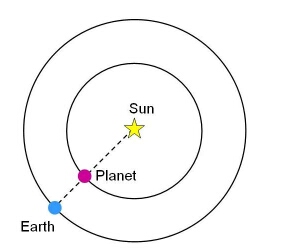

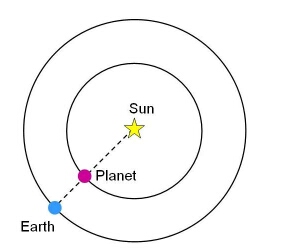

An inferior conjunction is when an object passes between us and the sun. Any object in space that orbits the sun closer than Earth’s orbit might pass through inferior conjunction from time to time, assuming its orbit lies more or less close to the ecliptic. Usually, though, when you hear the words inferior conjunction, astronomers are speaking of the planets Venus and Mercury, which orbit the sun inside Earth’s orbit. Astronomers sometimes refer to Venus and Mercury as inferior planets. When they’re at or near inferior conjunction, we can’t see them. They’re hidden in the sun’s glare. Occasionally, though, Venus or Mercury can be seen to transit across the sun’s disk at inferior conjunction. Consider also the moon. It passes between the Earth and sun at new moon once each month. Therefore, it would be correct, if a little weird, to say that the moon is at inferior conjunction when it’s at its new phase.

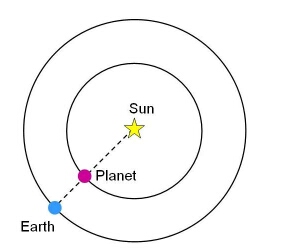

This diagram depicts an inferior conjunction of Venus or Mercury. At such times, the inner planet passes between the Earth and sun. Image via COSMOS.

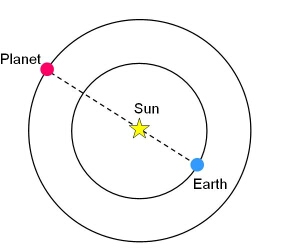

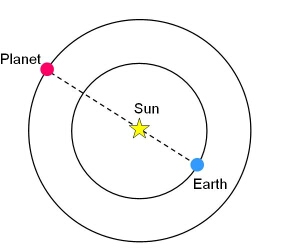

A superior conjunction is when an object passes behind the sun from our point of view. Think of Venus or Mercury again. Half of their conjunctions with the sun – when they are brought together with the sun on our sky’s dome – are inferior conjunctions, and half are superior conjunctions. It’s kind of fun to imagine them on an endless cycle of passing in front of the sun, as seen from Earth, then behind it, and back again, like watching squirrels running around a tree. Meanwhile, the superior planets – or planets farther from the sun than Earth such as Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – can never be at inferior conjunction. They can never pass between us and the sun. Thus the superior planets only have superior conjunctions.

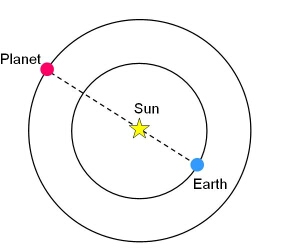

A superior conjunction happens when a planet – or asteroid or comet – sweeps behind the sun from Earth. At such times, as viewed from above the solar system, a straight line joins the object with the Earth and sun, and the object is on the opposite side of the sun from the Earth. Image via COSMOS.

The most common type of conjunction, though, doesn’t involve the sun. Any time two objects pass each other on the sky’s dome, they’re said to be at conjunction. These sorts of conjunctions – maybe between two planets, or a planet and a star, or a planet or star and the moon – happen multiple times every month. They are beautiful. The view can stop you in your tracks. For example, if you were fortunate enough to have looked at the moon on July 21, 1969, as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin headed home from the Sea of Tranquility, you’d have seen the moon in conjunction with Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo. The two were only about two degrees apart that night. That’s less than the width of a finger held out at arm’s length.

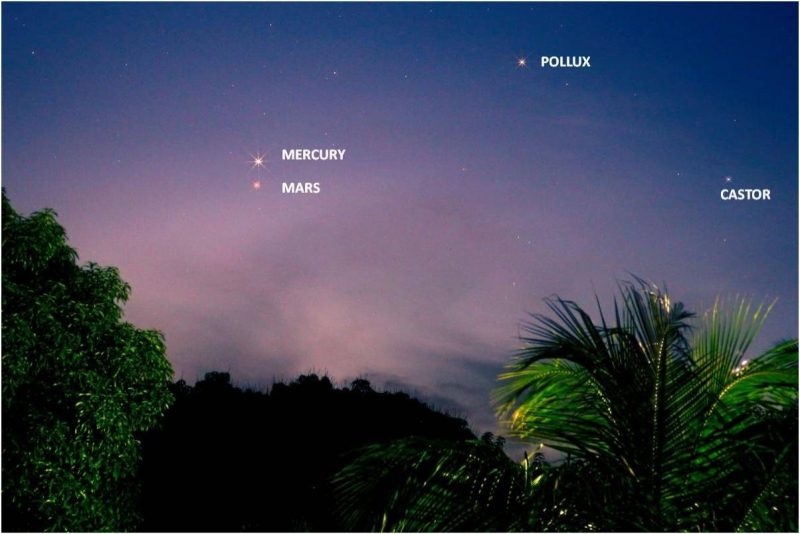

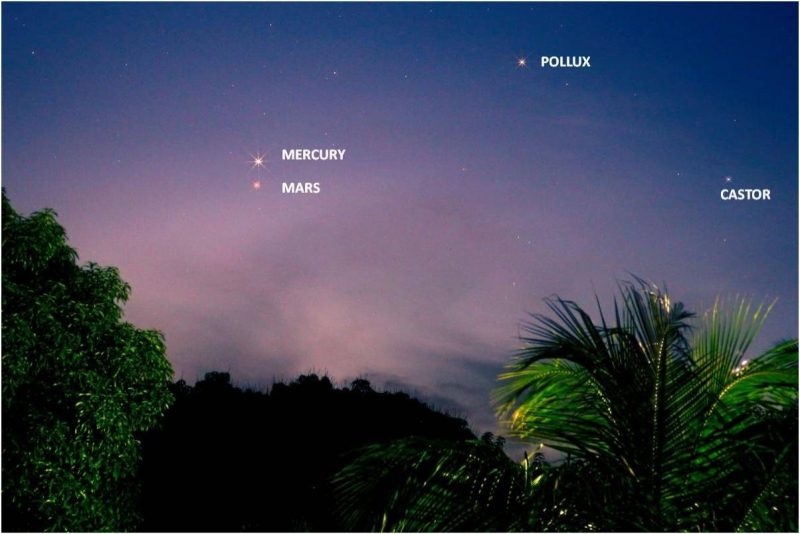

There are always a few particularly good conjunctions every year. In 2019, the closest conjunction of two planets happened on June 18, between Mercury and Mars. They passed exceedingly close to each other, with Mercury only sweeping only 0.2 degrees north of Mars on the sky’s dome. Unfortunately, the two were low in the evening twilight sky at the time, so they weren’t easy to see, but some photographers in the EarthSky community caught them, as you can see from the image below:

Here are some beautiful conjunctions coming up, which you can see easily.

On July 8 and 9, the moon will sweep past the bright star Spica in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Read more.

On July 13, the nearly full moon and Jupiter will be only about 3.5 degrees apart, with the bright star Antares just another seven degrees farther. Read more.

On July 15, the full moon will be just two degrees from Saturn, which itself will be less than a week past its yearly opposition, when Earth went between Saturn and the sun. Read more.

On July 25, the moon will sweep past Uranus. This conjunction won’t be so easy to see as the others mentioned here, because Uranus is so faint. It’ll be mostly drowned in the moon’s glare. But this conjunction will be possible to contemplate, and you can use the moon on this night to get oriented for seeing Uranus later on. Read more.

On July 26 to 28, the moon will be sweeping through the constellation Taurus the Bull, passing the Pleiades star cluster and the bright red star Aldebaran. Read more.

Toward the end of 2019, Venus will be less than two degrees from Jupiter on November 24, and then less than two degrees from Saturn on December 11. These movements of Jupiter and Saturn are building to a great conjunction of the two on December 21, 2020. That night, the two giant planets will be only six arc minutes apart! That conjunction might be so close that it could be hard to see where one ends and the other begins.

Learn when to expect conjunctions via EarthSky’s monthly planet guide.

Or keep an eye on EarthSky Tonight, to follow each month’s conjunctions

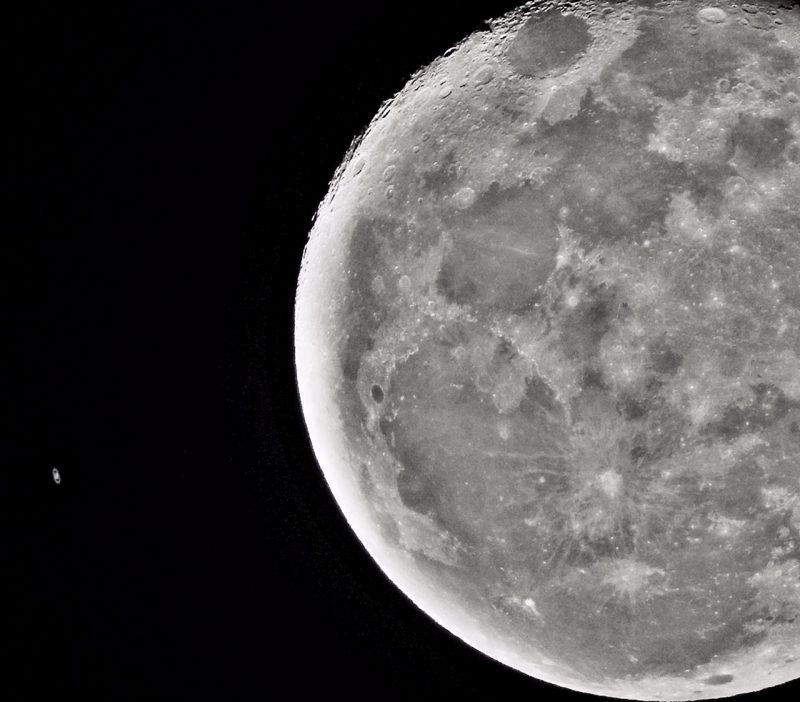

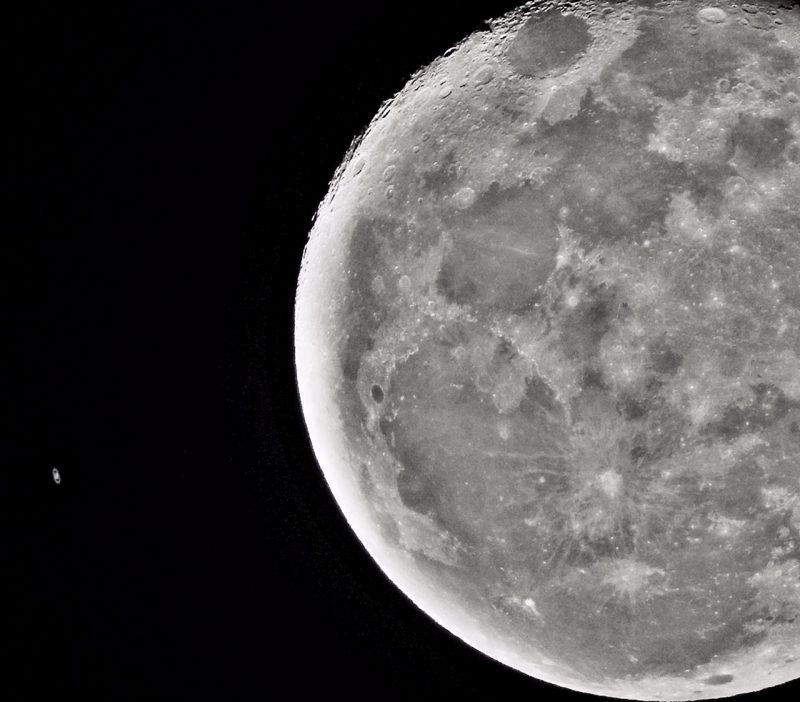

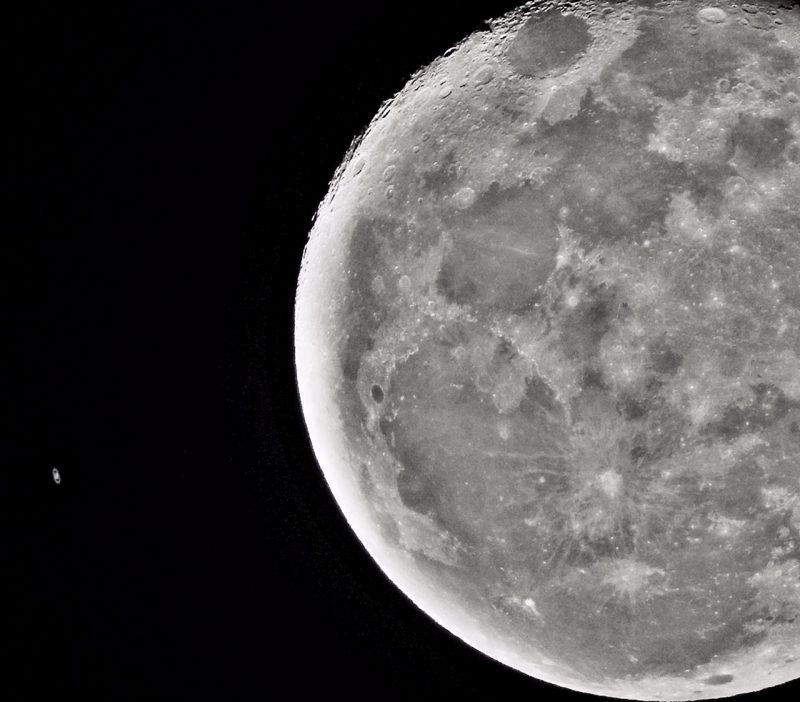

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Helio C. Vital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, caught the ringed planet Saturn (on left) when the moon swept near on June 19, 2019. He pointed out that Saturn was 3,000 times farther away from Earth than the moon that night. Thanks, Helio!

People often think about the night sky as being permanent and unchanging, at least on a human scale. If you make a point of watching the skies often, though, you’ve probably noticed that’s not exactly true. The stars don’t move relative to each other, but they do move across the sky over the course of a single night, as Earth spins under the sky. And, from one night to the next, stars rise and set four minutes earlier each day, as Earth orbits the sun.

Once you’ve found the ecliptic, you can see where the real action is. Because they are relatively close to us, the planets and moon do move relative to each other and the stars, and quickly, from our point of view. They change their positions, appear to move closer together and father apart, and sometimes pass by each other in the sky, coming to conjunction.

Of all of the pleasures of watching the skies, seeing these changes among our nearest neighbors is among the greatest.

Bottom line: When you hear the word conjunction in astronomy, you know it means two objects close together on our sky’s dome. Like so many things in life, conjunctions are just our point of view. In reality, these great worlds in space are still very far apart and only appear close to each other in our sky.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2N4Ndht

Example of a conjunction involving Venus and the Pleiades cluster, via Tom Wildoner at LeisurelyScientist.com.

Occasionally two or more objects meet up with each other in our sky. Astronomers use the word conjunction to describe these meetings. Technically speaking, objects are said to be in conjunction in that instant when they have the same right ascension on our sky’s dome. Practically speaking, objects in conjunction will likely be visible near each other for some days.

The word conjunction comes from Latin, meaning to join together. Maybe you remember the old Conjunction Junction cartoons from the 1970s. In language, conjunctions relate to clauses brought together in sentences. In astronomy, conjunctions relate to two or more objects brought together in the sky.

An astronomical conjunction describes a few different types of meetings. The first two types we’re describing here – inferior and superior conjunctions – involve the sun and thus can’t be seen.

An inferior conjunction is when an object passes between us and the sun. Any object in space that orbits the sun closer than Earth’s orbit might pass through inferior conjunction from time to time, assuming its orbit lies more or less close to the ecliptic. Usually, though, when you hear the words inferior conjunction, astronomers are speaking of the planets Venus and Mercury, which orbit the sun inside Earth’s orbit. Astronomers sometimes refer to Venus and Mercury as inferior planets. When they’re at or near inferior conjunction, we can’t see them. They’re hidden in the sun’s glare. Occasionally, though, Venus or Mercury can be seen to transit across the sun’s disk at inferior conjunction. Consider also the moon. It passes between the Earth and sun at new moon once each month. Therefore, it would be correct, if a little weird, to say that the moon is at inferior conjunction when it’s at its new phase.

This diagram depicts an inferior conjunction of Venus or Mercury. At such times, the inner planet passes between the Earth and sun. Image via COSMOS.

A superior conjunction is when an object passes behind the sun from our point of view. Think of Venus or Mercury again. Half of their conjunctions with the sun – when they are brought together with the sun on our sky’s dome – are inferior conjunctions, and half are superior conjunctions. It’s kind of fun to imagine them on an endless cycle of passing in front of the sun, as seen from Earth, then behind it, and back again, like watching squirrels running around a tree. Meanwhile, the superior planets – or planets farther from the sun than Earth such as Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune – can never be at inferior conjunction. They can never pass between us and the sun. Thus the superior planets only have superior conjunctions.

A superior conjunction happens when a planet – or asteroid or comet – sweeps behind the sun from Earth. At such times, as viewed from above the solar system, a straight line joins the object with the Earth and sun, and the object is on the opposite side of the sun from the Earth. Image via COSMOS.

The most common type of conjunction, though, doesn’t involve the sun. Any time two objects pass each other on the sky’s dome, they’re said to be at conjunction. These sorts of conjunctions – maybe between two planets, or a planet and a star, or a planet or star and the moon – happen multiple times every month. They are beautiful. The view can stop you in your tracks. For example, if you were fortunate enough to have looked at the moon on July 21, 1969, as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin headed home from the Sea of Tranquility, you’d have seen the moon in conjunction with Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo. The two were only about two degrees apart that night. That’s less than the width of a finger held out at arm’s length.

There are always a few particularly good conjunctions every year. In 2019, the closest conjunction of two planets happened on June 18, between Mercury and Mars. They passed exceedingly close to each other, with Mercury only sweeping only 0.2 degrees north of Mars on the sky’s dome. Unfortunately, the two were low in the evening twilight sky at the time, so they weren’t easy to see, but some photographers in the EarthSky community caught them, as you can see from the image below:

Here are some beautiful conjunctions coming up, which you can see easily.

On July 8 and 9, the moon will sweep past the bright star Spica in the constellation Virgo the Maiden. Read more.

On July 13, the nearly full moon and Jupiter will be only about 3.5 degrees apart, with the bright star Antares just another seven degrees farther. Read more.

On July 15, the full moon will be just two degrees from Saturn, which itself will be less than a week past its yearly opposition, when Earth went between Saturn and the sun. Read more.

On July 25, the moon will sweep past Uranus. This conjunction won’t be so easy to see as the others mentioned here, because Uranus is so faint. It’ll be mostly drowned in the moon’s glare. But this conjunction will be possible to contemplate, and you can use the moon on this night to get oriented for seeing Uranus later on. Read more.

On July 26 to 28, the moon will be sweeping through the constellation Taurus the Bull, passing the Pleiades star cluster and the bright red star Aldebaran. Read more.

Toward the end of 2019, Venus will be less than two degrees from Jupiter on November 24, and then less than two degrees from Saturn on December 11. These movements of Jupiter and Saturn are building to a great conjunction of the two on December 21, 2020. That night, the two giant planets will be only six arc minutes apart! That conjunction might be so close that it could be hard to see where one ends and the other begins.

Learn when to expect conjunctions via EarthSky’s monthly planet guide.

Or keep an eye on EarthSky Tonight, to follow each month’s conjunctions

View at EarthSky Community Photos. | Helio C. Vital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, caught the ringed planet Saturn (on left) when the moon swept near on June 19, 2019. He pointed out that Saturn was 3,000 times farther away from Earth than the moon that night. Thanks, Helio!

People often think about the night sky as being permanent and unchanging, at least on a human scale. If you make a point of watching the skies often, though, you’ve probably noticed that’s not exactly true. The stars don’t move relative to each other, but they do move across the sky over the course of a single night, as Earth spins under the sky. And, from one night to the next, stars rise and set four minutes earlier each day, as Earth orbits the sun.

Once you’ve found the ecliptic, you can see where the real action is. Because they are relatively close to us, the planets and moon do move relative to each other and the stars, and quickly, from our point of view. They change their positions, appear to move closer together and father apart, and sometimes pass by each other in the sky, coming to conjunction.

Of all of the pleasures of watching the skies, seeing these changes among our nearest neighbors is among the greatest.

Bottom line: When you hear the word conjunction in astronomy, you know it means two objects close together on our sky’s dome. Like so many things in life, conjunctions are just our point of view. In reality, these great worlds in space are still very far apart and only appear close to each other in our sky.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2N4Ndht