The word ‘legacy’ is often overused, but not about the late Baroness Tessa Jowell. I only worked with her briefly, during a stint as a Parliamentary researcher in the mid-90s but, as for practically everyone who met her, her warmth, her commitment to collaboration, and her determination to tackle seemingly immovable obstacles, left a lasting impression on me.

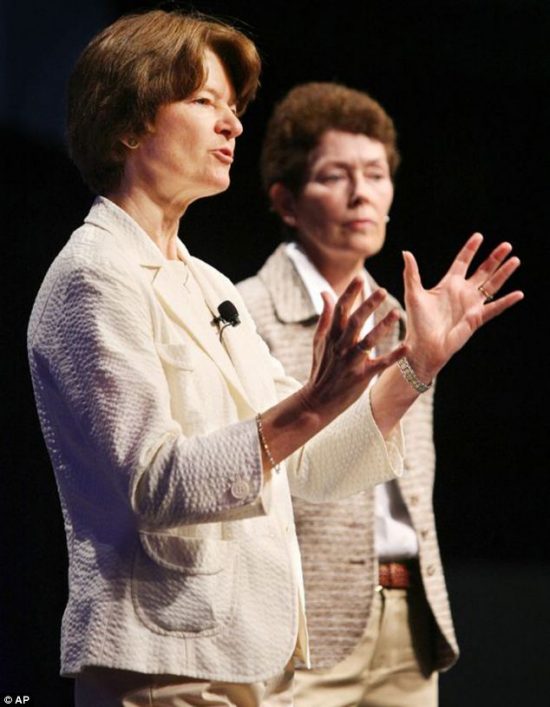

Baroness Tessa Jowell. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

They were qualities that helped her achieve so much in her life and career. Sure Start and the Olympic bid were merely the culmination of a life that saw her ceaselessly champion the less fortunate and underprivileged, first as a social worker, then as a politician.

In January 2018, in the late stages of treatment for an incurable brain tumour, she rose in the House of Lords to highlight the need to break down barriers preventing more research into her condition. Few will forget the steely passion with which she spoke. “For what would every cancer patient want?” she asked. “To know that the best, the latest science was being used – wherever in the world it was developed, whoever began it.”

Last week, I had the privilege – as chief executive of Cancer Research UK – to announce three new multimillion pound projects inspired, in part, by Tessa’s legacy. It gave me cause to reflect on how these projects came into being, how they exemplify the qualities that Tessa sought to champion – and how they drive me in leading one of the UK’s largest charities.

Breaking down barriers

Tessa was a change-maker, and knew first-hand that complex problems rarely have simple solutions. In the field of cancer research, there are few problems more challenging than brain tumours.

The brain’s incredible complexity allows you to read these words, to love, to hope and to mourn. Tumours that affect the brain are diseases – plural, there are more than 130 different types – arise in the organ that carries our very self. This complexity means that advances in understanding how the brain develops – and how cancers start and grow – have lagged behind advances elsewhere. A particular challenge is that brain itself is wrapped in a complex layer called the blood-brain barrier – any drugs that are to effectively treat brain tumours need to cross it. But all too often, brain tumour drugs are ‘repurposed’ from other fields of medicine – even modern targeted drugs. Finding new ways forward literally means working across barriers.

Bringing people together

Tessa was also a convener, and these projects are, on every level, collaborative. They bring together researchers from across the UK with those in Canada and the United States, with skills ranging from basic laboratory biology to chemical engineering and data science. And they’re funded thanks to a partnership between two medical research charities – ourselves and The Brain Tumour Charity.

They’re the culmination of a journey that started several years ago, when we made a commitment to boost funding into several of the hardest-to-treat cancers – brain tumours among them. Medical research isn’t simply a matter of pouring more money into a given area – to make a difference, funders like Cancer Research UK rely on a vibrant research community to bring forward cutting-edge ideas. But compared to other forms of cancer, the field of brain tumour research lacked such a network. So we set out to create one.

In bringing together cancer researchers, neuro-oncologists, surgeons, patients and funders, we helped map out the biggest challenges in brain tumour research – and made a commitment last year to fund research teams who could help solve them. I hope Tessa would have been proud of the outcome. They certainly inspired an overwhelming sense of hope and progress when announced at an event in the House of Lords last week. It was heartening to hear people from across the political spectrum commit to future progress, and to help people affected by this awful disease.

An inspiration

On a personal level, as a woman leading a complex medical research charity, I look back on Tessa’s career, leadership and legacy, and draw further inspiration. Fundamentally, charities exist to provide funding to overcome barriers. But they are also there to bring people together, to define a shared mission, and to act as vehicles for change. There are more than 200 forms of cancer, each posing a unique challenge – both to the medical and scientific community as they strive for future progress, but above all for people affected by them.

Tessa’s daughter Jess Mills’ words rung true at the event: “It is up to all of us here to ensure we are never deterred by a sense of the impossible, but inspired by it”. It’s an inspiration that must keep us moving forward, together, because there is still so much more to do, for all people affected by cancer.

Michelle Mitchell is chief executive of Cancer Research UK

Read more about the three teams funded through our Brain Tumour Awards.

from Cancer Research UK – Science blog http://bit.ly/2ZIMeoX

The word ‘legacy’ is often overused, but not about the late Baroness Tessa Jowell. I only worked with her briefly, during a stint as a Parliamentary researcher in the mid-90s but, as for practically everyone who met her, her warmth, her commitment to collaboration, and her determination to tackle seemingly immovable obstacles, left a lasting impression on me.

Baroness Tessa Jowell. Credit: Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0

They were qualities that helped her achieve so much in her life and career. Sure Start and the Olympic bid were merely the culmination of a life that saw her ceaselessly champion the less fortunate and underprivileged, first as a social worker, then as a politician.

In January 2018, in the late stages of treatment for an incurable brain tumour, she rose in the House of Lords to highlight the need to break down barriers preventing more research into her condition. Few will forget the steely passion with which she spoke. “For what would every cancer patient want?” she asked. “To know that the best, the latest science was being used – wherever in the world it was developed, whoever began it.”

Last week, I had the privilege – as chief executive of Cancer Research UK – to announce three new multimillion pound projects inspired, in part, by Tessa’s legacy. It gave me cause to reflect on how these projects came into being, how they exemplify the qualities that Tessa sought to champion – and how they drive me in leading one of the UK’s largest charities.

Breaking down barriers

Tessa was a change-maker, and knew first-hand that complex problems rarely have simple solutions. In the field of cancer research, there are few problems more challenging than brain tumours.

The brain’s incredible complexity allows you to read these words, to love, to hope and to mourn. Tumours that affect the brain are diseases – plural, there are more than 130 different types – arise in the organ that carries our very self. This complexity means that advances in understanding how the brain develops – and how cancers start and grow – have lagged behind advances elsewhere. A particular challenge is that brain itself is wrapped in a complex layer called the blood-brain barrier – any drugs that are to effectively treat brain tumours need to cross it. But all too often, brain tumour drugs are ‘repurposed’ from other fields of medicine – even modern targeted drugs. Finding new ways forward literally means working across barriers.

Bringing people together

Tessa was also a convener, and these projects are, on every level, collaborative. They bring together researchers from across the UK with those in Canada and the United States, with skills ranging from basic laboratory biology to chemical engineering and data science. And they’re funded thanks to a partnership between two medical research charities – ourselves and The Brain Tumour Charity.

They’re the culmination of a journey that started several years ago, when we made a commitment to boost funding into several of the hardest-to-treat cancers – brain tumours among them. Medical research isn’t simply a matter of pouring more money into a given area – to make a difference, funders like Cancer Research UK rely on a vibrant research community to bring forward cutting-edge ideas. But compared to other forms of cancer, the field of brain tumour research lacked such a network. So we set out to create one.

In bringing together cancer researchers, neuro-oncologists, surgeons, patients and funders, we helped map out the biggest challenges in brain tumour research – and made a commitment last year to fund research teams who could help solve them. I hope Tessa would have been proud of the outcome. They certainly inspired an overwhelming sense of hope and progress when announced at an event in the House of Lords last week. It was heartening to hear people from across the political spectrum commit to future progress, and to help people affected by this awful disease.

An inspiration

On a personal level, as a woman leading a complex medical research charity, I look back on Tessa’s career, leadership and legacy, and draw further inspiration. Fundamentally, charities exist to provide funding to overcome barriers. But they are also there to bring people together, to define a shared mission, and to act as vehicles for change. There are more than 200 forms of cancer, each posing a unique challenge – both to the medical and scientific community as they strive for future progress, but above all for people affected by them.

Tessa’s daughter Jess Mills’ words rung true at the event: “It is up to all of us here to ensure we are never deterred by a sense of the impossible, but inspired by it”. It’s an inspiration that must keep us moving forward, together, because there is still so much more to do, for all people affected by cancer.

Michelle Mitchell is chief executive of Cancer Research UK

Read more about the three teams funded through our Brain Tumour Awards.

from Cancer Research UK – Science blog http://bit.ly/2ZIMeoX