On June 18, 2019, the big and bright waning gibbous moon shines quite close to Saturn, the sixth planet outward from the sun. Although Saturn is a notch brighter than a 1st-magnitude star, you might have some difficulty seeing Saturn in the moon’s glare tonight. That more brilliant “star” above the moon and Saturn is another planet, the fifth planet outward from the sun and largest planet in our solar system, Jupiter. You should have no trouble viewing Jupiter, as it’s the fourth-brightest celestial object to light up the heavens, after the sun, moon and planet Venus.

However, there’s no chance of mistaking Venus for Jupiter – or vice versa. Jupiter is out first thing at dusk, and shines from dusk until dawn. Venus, meanwhile, is in the morning sky, rising in the east about an hour before sunrise. In other words, Jupiter is easy to see at any time of the night in June 2019. Venus – although technically brighter – demands a deliberate effort as it sits low in the glow of dawn.

And speaking of deliberate efforts … Mars and Mercury have a close pairing on this date, too. They are not easy to see, however, sitting low in the west after sunset. See the chart below.

Look westward for the close pairing of the planets Mercury and Mars on June 18, 2019. You may need binoculars to glimpse fainter Mars next to brighter Mercury.

On the other hand, the moon and Saturn will be easy to see, close together, as soon as your sky gets dark. Of course, when we say that the moon and Saturn are close together, we mean they appear on nearly the same line of sight. The two are nowhere close together in space. The moon, our closest celestial neighbor, lies about 246 thousand miles (396 thousand km) distant. Saturn, the most distant world that we can easily see with the unaided eye, resides at better than 3,400 times the moon’s distance from Earth tonight.

Saturn lodges 9.1 astronomical units (AU) from Earth right now. One astronomical unit = the Earth’s mean distance from the sun.

Click here to know the moon’s present distance from Earth.

Click here to know Saturn’s present distance from the Earth and sun.

Consulting an astronomical almanac, we find that the moon passes 0.4 degrees south of the planet Saturn on June 19 at 3:58 Universal Time. (For reference, the moon’s angular diameter equals about 1/2 degrees or 0.5 degree.) At the Central Time zone in North America, that means the moon passes 0.4 degrees south of Saturn on June 18 at 10:58 p.m. CDT (UTC-5 hours).

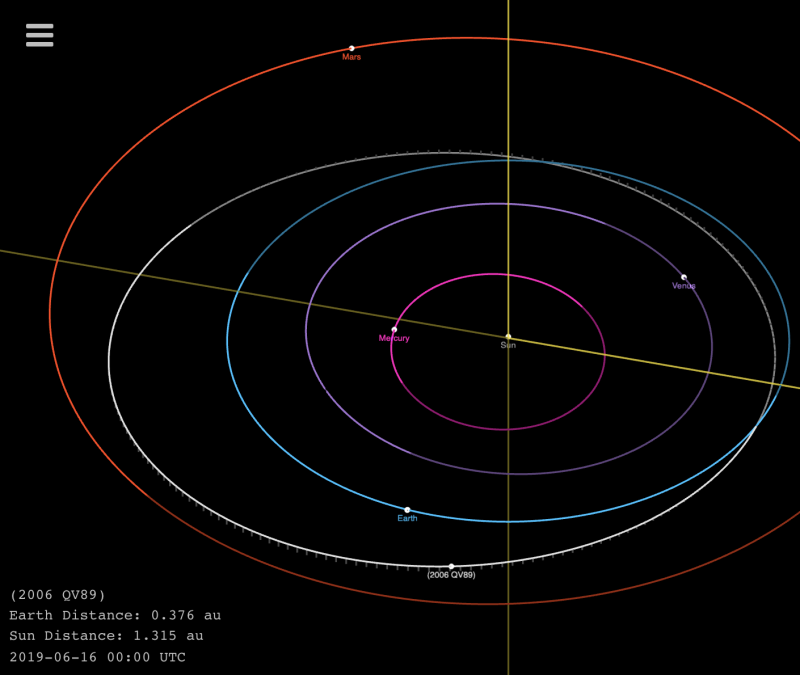

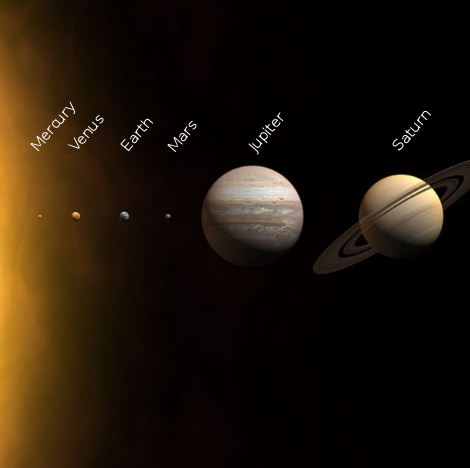

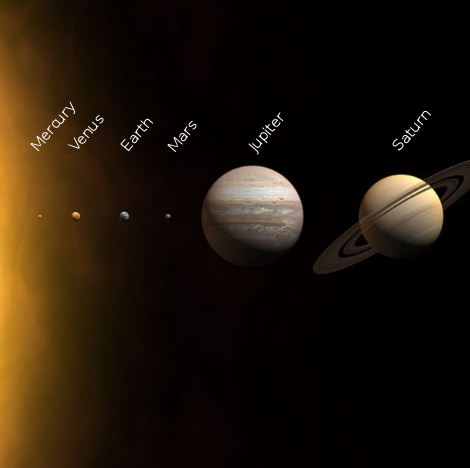

This illustration shows the bright planets, plus Earth, in their order outward from the sun. Their relative sizes are approximately right, but their distances from one another are – in reality – much more vast.

Now brace yourself for a major caveat! Whenever an astronomical almanac tells you how many degrees the moon passes to the north or south of a planet or bright star, it means as viewed from the center of the Earth. From various places on the Earth’s surface, the angular distance between the moon and Saturn is not the same. The farther north you live on the globe, the farther that the moon passes to the south of Saturn; and the farther south you live, the closer that the moon swings by Saturn.

In fact, if you live as far south as southern South America (Chile, Argentina), the moon will occult, or pass directly in front of Saturn, momentarily hiding this world from view. For example, from Buenos Aries, Argentina, the moon will occult Saturn from 11:25 p.m. on June 18, 2019 until 12:15 a.m. local time on June 19, 2019. If you live within in the occultation viewing area (see the map below), find out when this occultation occurs in your sky in Universal Time. Here’s how to convert Universal Time to local time.

See the solid white lines on the worldwide map? That’s where the occultation of Saturn happens in a nighttime sky on the night of June 18-19, 2019. Click here for more information.

Bottom line: As darkness falls this evening – on June 18, 2019 – look for the moon and Saturn to couple up tonight from early evening until morning dawn.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2wY7bQa

On June 18, 2019, the big and bright waning gibbous moon shines quite close to Saturn, the sixth planet outward from the sun. Although Saturn is a notch brighter than a 1st-magnitude star, you might have some difficulty seeing Saturn in the moon’s glare tonight. That more brilliant “star” above the moon and Saturn is another planet, the fifth planet outward from the sun and largest planet in our solar system, Jupiter. You should have no trouble viewing Jupiter, as it’s the fourth-brightest celestial object to light up the heavens, after the sun, moon and planet Venus.

However, there’s no chance of mistaking Venus for Jupiter – or vice versa. Jupiter is out first thing at dusk, and shines from dusk until dawn. Venus, meanwhile, is in the morning sky, rising in the east about an hour before sunrise. In other words, Jupiter is easy to see at any time of the night in June 2019. Venus – although technically brighter – demands a deliberate effort as it sits low in the glow of dawn.

And speaking of deliberate efforts … Mars and Mercury have a close pairing on this date, too. They are not easy to see, however, sitting low in the west after sunset. See the chart below.

Look westward for the close pairing of the planets Mercury and Mars on June 18, 2019. You may need binoculars to glimpse fainter Mars next to brighter Mercury.

On the other hand, the moon and Saturn will be easy to see, close together, as soon as your sky gets dark. Of course, when we say that the moon and Saturn are close together, we mean they appear on nearly the same line of sight. The two are nowhere close together in space. The moon, our closest celestial neighbor, lies about 246 thousand miles (396 thousand km) distant. Saturn, the most distant world that we can easily see with the unaided eye, resides at better than 3,400 times the moon’s distance from Earth tonight.

Saturn lodges 9.1 astronomical units (AU) from Earth right now. One astronomical unit = the Earth’s mean distance from the sun.

Click here to know the moon’s present distance from Earth.

Click here to know Saturn’s present distance from the Earth and sun.

Consulting an astronomical almanac, we find that the moon passes 0.4 degrees south of the planet Saturn on June 19 at 3:58 Universal Time. (For reference, the moon’s angular diameter equals about 1/2 degrees or 0.5 degree.) At the Central Time zone in North America, that means the moon passes 0.4 degrees south of Saturn on June 18 at 10:58 p.m. CDT (UTC-5 hours).

This illustration shows the bright planets, plus Earth, in their order outward from the sun. Their relative sizes are approximately right, but their distances from one another are – in reality – much more vast.

Now brace yourself for a major caveat! Whenever an astronomical almanac tells you how many degrees the moon passes to the north or south of a planet or bright star, it means as viewed from the center of the Earth. From various places on the Earth’s surface, the angular distance between the moon and Saturn is not the same. The farther north you live on the globe, the farther that the moon passes to the south of Saturn; and the farther south you live, the closer that the moon swings by Saturn.

In fact, if you live as far south as southern South America (Chile, Argentina), the moon will occult, or pass directly in front of Saturn, momentarily hiding this world from view. For example, from Buenos Aries, Argentina, the moon will occult Saturn from 11:25 p.m. on June 18, 2019 until 12:15 a.m. local time on June 19, 2019. If you live within in the occultation viewing area (see the map below), find out when this occultation occurs in your sky in Universal Time. Here’s how to convert Universal Time to local time.

See the solid white lines on the worldwide map? That’s where the occultation of Saturn happens in a nighttime sky on the night of June 18-19, 2019. Click here for more information.

Bottom line: As darkness falls this evening – on June 18, 2019 – look for the moon and Saturn to couple up tonight from early evening until morning dawn.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2wY7bQa