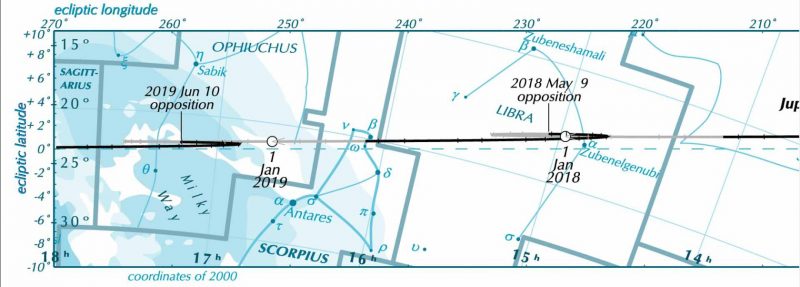

Infrared image of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot from the Gemini Observatory on May 18, 2018. The image shows a hook-like cloud on the western side and a long streamer on the eastern side. Image via Gemini Observatory/AURA/NSF/JPL-Caltech/NASA.

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is iconic, the largest and longest-lasting storm ever seen in the solar system. It has been around for at least hundreds of years, but is it now nearing its end? Recent observations show that the storm seems to be coming apart, with streamers “peeling off” the main spot as often as every week. The streamers and associated features have also been described as “hooks,” “blades” and “flakes” breaking off the main Great Red Spot. Some reports have called this process “unraveling” although that isn’t really the best description. Could the Great Red Spot actually be self-destructing? Is it nearing its end?

Amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley in Australia photographed one such streamer on May 19, 2019, which stretched more than 10,000 km (6,000 miles) from the Great Red Spot, joining up with a nearby jet stream. He saw the same features again on May 22. As he noted:

I haven’t seen this before in my 17-or-so years of imaging Jupiter.

Wesley was also recently featured in Australia’s ABC News about his photographs of the Great Red Spot:

It’s been quite dramatic … [the images have been] showing the spot in a state that nobody’s ever seen before. It’s suddenly, in the last two months or so, started to undergo these massive peeling, or flaking events. No one has really seen this happen before and no one can really predict what is going to happen.

Another amateur astronomer, Christopher Go, also observed a reddish extension on the left side of the Great Red Spot on May 17.

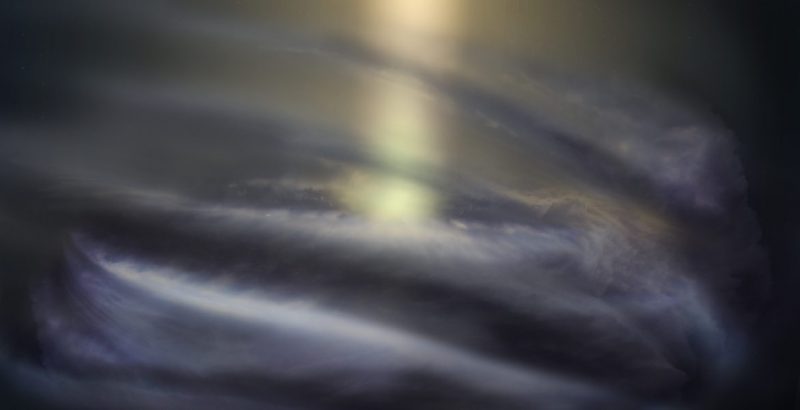

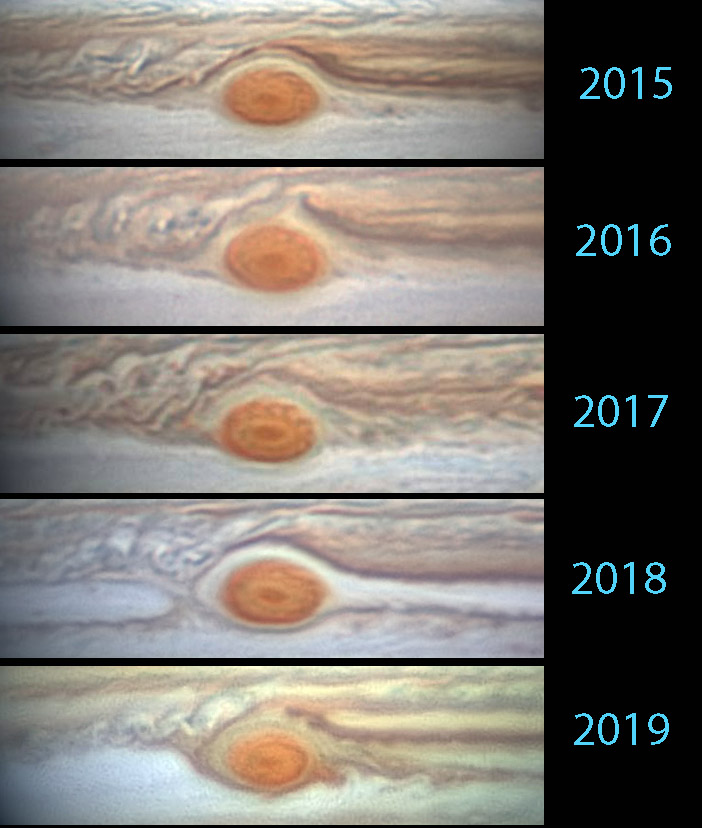

You can see subtle changes in and around the Great Red Spot in this sequence of images taken over the past 5 years. The wraparound cloud shaped like a spoon appears to have formed sometime last spring. Image via Christopher Go/SkyandTelescope.com.

Jupiter as seen by amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley on May 19, 2019.

Another view of Jupiter from Anthony Wesley on May 22, 2019.

A similar but smaller streamer was seen back in May 2017 by the Gemini North telescope (part of the Gemini Observatory) using adaptive optics, on the summit of Maunakea in Hawaii. The adaptive optics remove distortions due to the turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere, producing extremely high-resolution images. Gemini can currently see features as small as Ireland on Jupiter. Glenn Orton of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) said he saw a hook-like feature on the western side of the Great Red Spot. He said:

Back in May, Gemini zoomed in on intriguing features in and around Jupiter’s Great Red Spot: including a swirling structure on the inside of the spot, a curious hook-like cloud feature on its western side and a lengthy, fine-structured wave extending off from its eastern side. Events like this show that there’s still much to learn about Jupiter’s atmosphere; the combination of Earth-based and spacecraft observations is a powerful one-two punch in exploring Jupiter.

The Gemini Observatory uses special filters that focus on specific colors of light that can penetrate the upper atmosphere and clouds of Jupiter. These images are sensitive to increasing absorption by mixtures of methane and hydrogen gas in Jupiter’s atmosphere. This is great for observing the details of the streamers, hooks, blades and flakes.

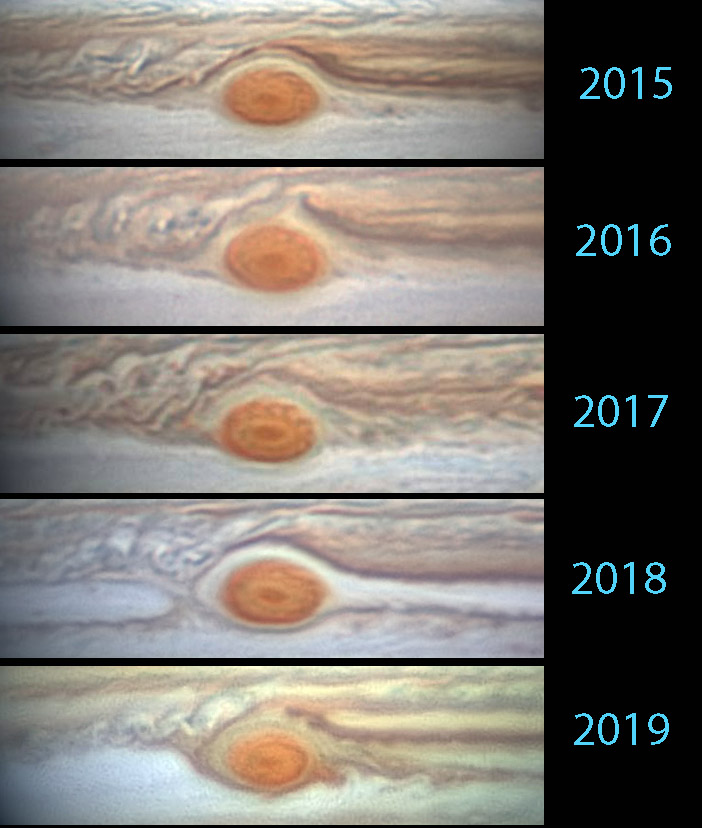

Closer views of the Great Red Spot from the Gemini Observatory on May 18, 2017 (top two panels) and January 11, 2017 (bottom panel), Image via Gemini Observatory/AURA/NSF/JPL-Caltech/NASA/UC Berkeley.

These features are unusual, and may indicate that the Great Red Spot itself is indeed breaking apart, after other observations have shown that the Spot has shrunk considerably in size in recent years. It used to be large enough to hold three Earths, but now could only hold about one or two. Wesley described the behavior of the streamers:

Each streamer appears to disconnect from the Great Red Spot and dissipate. Then, after about a week, a new streamer forms and the process repeats. You have to be lucky to catch it happening. Jupiter spins on its axis every 10 hours and the Great Red Spot is not always visible. A joint effort between many amateurs is underway to get clear images of the process.

It’s not just astronomers on Earth who have been observing these changes. NASA’s Juno spacecraft currently orbiting Jupiter has as well. Some of its images, from its 17th and 18th flybys, have shown the same streamers, blades and flakes. The red-colored flakes were seen to last for more than a week. Juno will fly over the Great Red Spot again in July 2019. Juno had also sometimes seen these features in the past, but they were rare until 2017. According to Orton:

Some observers implied that these [blades] were induced by the arrival of vortices in a jet just south of the Great Red Spot moving from east to west that enter a dark area surrounding it that is characterized by deeper clouds, known as the ‘Red Spot Hollow.’ Stay tuned, as the dark region around the Great Red Spot is growing in length, and we’ll see what happens next.

Jupiter and the Great Red Spot as seen by the Juno spacecraft on February 12, 2019. A large “hook” can clearly be seen on the western side of the spot. Image via NASA/SwRI/MSSS.

Juno was launched in August 2011 and began orbiting Jupiter in early July 2016. It has already transformed our understanding of how Jupiter formed and evolved, from its thick cloud layers to its deepest core.

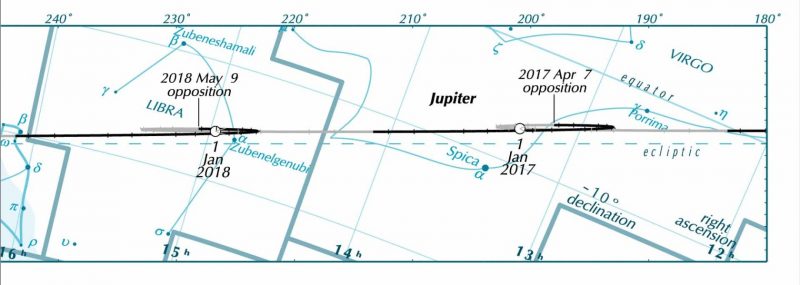

June 2019 will be a great time to observe Jupiter too, as the planet will be four times brighter than the star Sirius, especially in the weeks and months around Jupiter’s opposition on June 10.

What exactly is happening with the Great Red Spot isn’t completely clear, and no one knows how long it may take for the Great Red Spot to completely disappear, if it does in our lifetimes, but it will be very interesting to see what happens in the months and years ahead. It would be missed, of course, if it did disappear, but that process would also provide scientists with valuable data on how Jupiter’s atmosphere behaves.

A closer view of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, as seen by Juno in 2017. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Roman Tkachenko.

Bottom line: Jupiter’s massive Great Red Spot has been acting a bit odd lately, and may be in the process of coming apart and even disappearing completely eventually. Continued observations will help determine what fate awaits the solar system’s biggest and longest-lived storm that has fascinated humanity for centuries.

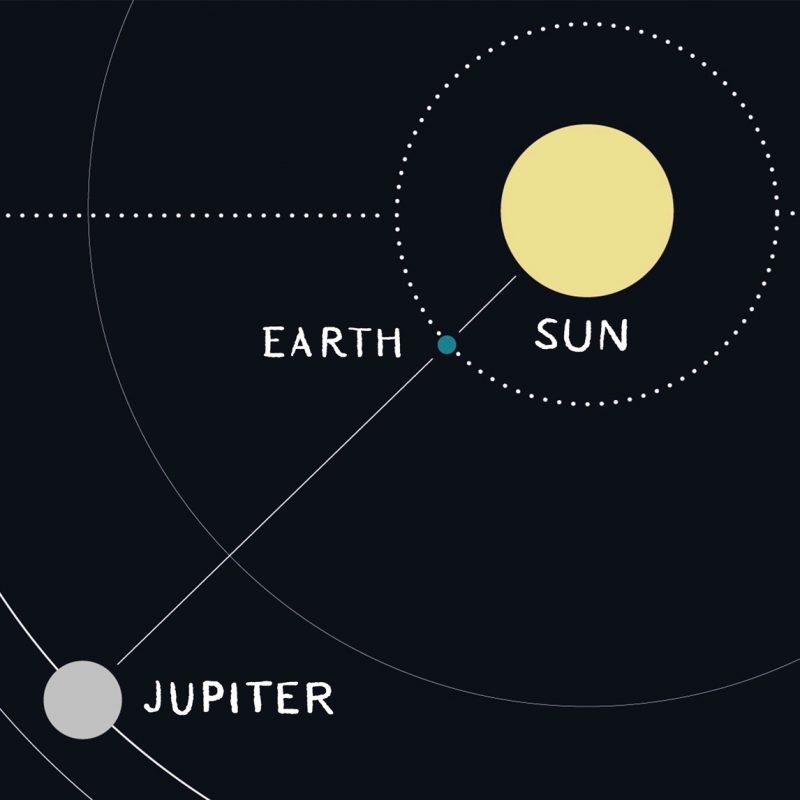

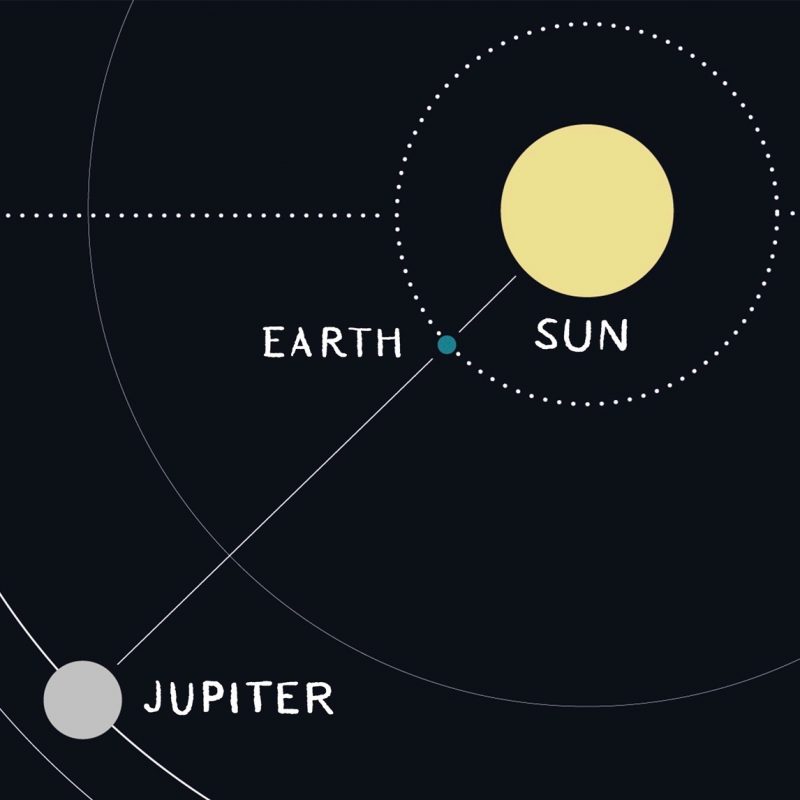

Read more: We go between Jupiter and the sun June 10, 2019

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2IyxmCe

Infrared image of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot from the Gemini Observatory on May 18, 2018. The image shows a hook-like cloud on the western side and a long streamer on the eastern side. Image via Gemini Observatory/AURA/NSF/JPL-Caltech/NASA.

Jupiter’s Great Red Spot is iconic, the largest and longest-lasting storm ever seen in the solar system. It has been around for at least hundreds of years, but is it now nearing its end? Recent observations show that the storm seems to be coming apart, with streamers “peeling off” the main spot as often as every week. The streamers and associated features have also been described as “hooks,” “blades” and “flakes” breaking off the main Great Red Spot. Some reports have called this process “unraveling” although that isn’t really the best description. Could the Great Red Spot actually be self-destructing? Is it nearing its end?

Amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley in Australia photographed one such streamer on May 19, 2019, which stretched more than 10,000 km (6,000 miles) from the Great Red Spot, joining up with a nearby jet stream. He saw the same features again on May 22. As he noted:

I haven’t seen this before in my 17-or-so years of imaging Jupiter.

Wesley was also recently featured in Australia’s ABC News about his photographs of the Great Red Spot:

It’s been quite dramatic … [the images have been] showing the spot in a state that nobody’s ever seen before. It’s suddenly, in the last two months or so, started to undergo these massive peeling, or flaking events. No one has really seen this happen before and no one can really predict what is going to happen.

Another amateur astronomer, Christopher Go, also observed a reddish extension on the left side of the Great Red Spot on May 17.

You can see subtle changes in and around the Great Red Spot in this sequence of images taken over the past 5 years. The wraparound cloud shaped like a spoon appears to have formed sometime last spring. Image via Christopher Go/SkyandTelescope.com.

Jupiter as seen by amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley on May 19, 2019.

Another view of Jupiter from Anthony Wesley on May 22, 2019.

A similar but smaller streamer was seen back in May 2017 by the Gemini North telescope (part of the Gemini Observatory) using adaptive optics, on the summit of Maunakea in Hawaii. The adaptive optics remove distortions due to the turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere, producing extremely high-resolution images. Gemini can currently see features as small as Ireland on Jupiter. Glenn Orton of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) said he saw a hook-like feature on the western side of the Great Red Spot. He said:

Back in May, Gemini zoomed in on intriguing features in and around Jupiter’s Great Red Spot: including a swirling structure on the inside of the spot, a curious hook-like cloud feature on its western side and a lengthy, fine-structured wave extending off from its eastern side. Events like this show that there’s still much to learn about Jupiter’s atmosphere; the combination of Earth-based and spacecraft observations is a powerful one-two punch in exploring Jupiter.

The Gemini Observatory uses special filters that focus on specific colors of light that can penetrate the upper atmosphere and clouds of Jupiter. These images are sensitive to increasing absorption by mixtures of methane and hydrogen gas in Jupiter’s atmosphere. This is great for observing the details of the streamers, hooks, blades and flakes.

Closer views of the Great Red Spot from the Gemini Observatory on May 18, 2017 (top two panels) and January 11, 2017 (bottom panel), Image via Gemini Observatory/AURA/NSF/JPL-Caltech/NASA/UC Berkeley.

These features are unusual, and may indicate that the Great Red Spot itself is indeed breaking apart, after other observations have shown that the Spot has shrunk considerably in size in recent years. It used to be large enough to hold three Earths, but now could only hold about one or two. Wesley described the behavior of the streamers:

Each streamer appears to disconnect from the Great Red Spot and dissipate. Then, after about a week, a new streamer forms and the process repeats. You have to be lucky to catch it happening. Jupiter spins on its axis every 10 hours and the Great Red Spot is not always visible. A joint effort between many amateurs is underway to get clear images of the process.

It’s not just astronomers on Earth who have been observing these changes. NASA’s Juno spacecraft currently orbiting Jupiter has as well. Some of its images, from its 17th and 18th flybys, have shown the same streamers, blades and flakes. The red-colored flakes were seen to last for more than a week. Juno will fly over the Great Red Spot again in July 2019. Juno had also sometimes seen these features in the past, but they were rare until 2017. According to Orton:

Some observers implied that these [blades] were induced by the arrival of vortices in a jet just south of the Great Red Spot moving from east to west that enter a dark area surrounding it that is characterized by deeper clouds, known as the ‘Red Spot Hollow.’ Stay tuned, as the dark region around the Great Red Spot is growing in length, and we’ll see what happens next.

Jupiter and the Great Red Spot as seen by the Juno spacecraft on February 12, 2019. A large “hook” can clearly be seen on the western side of the spot. Image via NASA/SwRI/MSSS.

Juno was launched in August 2011 and began orbiting Jupiter in early July 2016. It has already transformed our understanding of how Jupiter formed and evolved, from its thick cloud layers to its deepest core.

June 2019 will be a great time to observe Jupiter too, as the planet will be four times brighter than the star Sirius, especially in the weeks and months around Jupiter’s opposition on June 10.

What exactly is happening with the Great Red Spot isn’t completely clear, and no one knows how long it may take for the Great Red Spot to completely disappear, if it does in our lifetimes, but it will be very interesting to see what happens in the months and years ahead. It would be missed, of course, if it did disappear, but that process would also provide scientists with valuable data on how Jupiter’s atmosphere behaves.

A closer view of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, as seen by Juno in 2017. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Roman Tkachenko.

Bottom line: Jupiter’s massive Great Red Spot has been acting a bit odd lately, and may be in the process of coming apart and even disappearing completely eventually. Continued observations will help determine what fate awaits the solar system’s biggest and longest-lived storm that has fascinated humanity for centuries.

Read more: We go between Jupiter and the sun June 10, 2019

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2IyxmCe