87 items this week, with 23 available as open access.

What are we doing on Mars?

We're from Earth, yet Included in this week's trawl of research articles are Streeter et al with Surface warming during the 2018/Mars Year 34 Global Dust Storm. Why are we visiting Mars today? Because the same storm that silenced the doughty Opportunity rover after over 14 years of operation yields an interesting research result on the dust-up's temporary effect on the Martian climate:

The impact of Mars’ 2018 Global Dust Storm (GDS) on surface and near‐surface air temperatures was investigated using an assimilation of Mars Climate Sounder (MCS) observations. Rather than simply resulting in cooling everywhere from solar absorption (average surface radiative flux fell 26 Wm‐2), the globally‐averaged result was a 0.9 K surface warming. These diurnally‐averaged surface temperature changes had a novel, highly non‐uniform spatial structure, with up to 16 K cooling/19 K warming. Net warming occurred in low thermal inertia (TI) regions, where rapid night‐time radiative cooling was compensated by increased longwave emission and scattering. This caused strong nightside warming, outweighing dayside cooling. The reduced surface‐air temperature gradient closely coupled surface and air temperatures, even causing local dayside air warming.

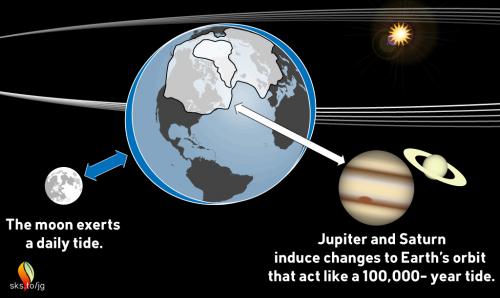

Note the similar causal mechanism and ultimate effect of increased surface temperatures to what a little additional CO2 in Earth's atmosphere produces. Despite a drastic reduction of surface energy delivery to Mars, night time temperatures rose and this effect was even true to some extent in day time.

Leaving aside dust not being gaseous, the principle and concerning difference between the two is that dust rapidly drops out of the atmosphere whether on Mars or at home, while the additional CO2 we've liberated into our local thin skin of gas will require several hundred years to find a permanent new home away from where it causes deleterious effects on our climate.

Lost in thought

It's continually surprising to see the almost laconic back-and-forth exploration of abstract economic matters as they apply to climate change, which to some of us seems to lack a sense of urgency or connection to the real world. Not to pick on them but simply as they appeared in this week's haul, as an example Mallapragada & Mignone bring us A theoretical basis for the equivalence between physical and economic climate metrics and implications for the choice of Global Warming Potential time horizon:

The global warming potential (GWP) is widely used in policy analysis, national greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting, and technology life cycle assessment (LCA) to compare the impact of non-CO2 GHG emissions to the impact of CO2 emissions. While the GWP is simple and versatile, different views about the appropriate choice of time horizon—and the factors that affect that choice—can impede decision-making. If the GWP is viewed as an approximation to a climate metric that more directly measures economic impact—the global damage potential (GDP)—then the time horizon may be viewed as a proxy for the discount rate. However, the validity of this equivalence rests on the theoretical basis used to equate the two metrics. In this paper, we develop a new theoretical basis for relating the GWP time horizon and the economic discount rate that avoids the most restrictive assumptions of prior studies, such as an assumed linear relationship between economic damages and temperature. We validate this approach with an extensive set of numerical experiments using an up-to-date climate emulator that represents state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks. The numerical results largely confirm the theoretical finding that, under certain reasonable assumptions, time horizons in the GWP of 100 years and 20 years are most consistent with discount rates of approximately 3% and 7% (or greater), respectively.

Introduction of the "discount rate" into thinking about climate change mitigation and adaptation costs and expenditures confuses simple and ignorant minds (such as the author of this blog entry). Application of a scrupulously calculated discount rate to the question of spending related to climate change is promised to yield a brighter future.To this layperson establishing this magic number appears to be a form of paralytic perfectionism and as well seems dependent on unreliable information about a future beyond our ken.

As a person who spends time on boats and yet fully intends to never fall overboard, I can spend a lot or a little on a "PFD" (personal flotation device) despite knowing full well that any such expenditure large or small will be much more productively employed in a true investment even at a very poor interest rate, per the advice of economic experts. The wisdom and promised benefits of not buying a PFD hold true until the exact moment when I pitch overboard into cold water and shortly am depending on the PFD for continued survival, at which point more riches in the future become crisply abstract. Surely if I'm dead I won't be able to grow my personal economy; staying alive appears to be a prime requirement for my successful economic outcome. Thus I choose to waste money now on a quality PFD despite it not being a rational choice in the formal economic sense.

Assuming we'll stay high and dry may drive the decision to not buy a PFD and instead invest elsewhere. Similarly, overweening fascination with and pursuit of establishing theoretically defensible discount rates in connection with climate change appears to hinge on a relatively static scenario of a functioning economy resembling to some degree what we've come to expect from the past: a machine producing more or less steady and uninterrupted growth. It seems arguable that assumptions required to model such an economy and produce an academically worthy and admirable result are not necessarily valid given the broadly agreed dire projections we face of global warming and its various knock-on disruptions; we're entering an era with challenges on a scale and breadth we've not yet encountered and so old rules may not apply.

What am I missing?

Ideally an actual economist would explain this in terms an ordinary layperson might understand. Coming up for air and offering some conclusions with clear directions based on the assumption we will be falling overboard and indeed have already lost our grip and footing— are clumsily plunging over the lifelines into a life-threatening circumstance— would be very helpful. Is there an argument for obtaining a PFD, the notionally irrational choice to spend money to buy some better luck, a wager to help assure a future?

Articles:

Observation of climate warming

Influence of instrumentation on long temperature time series

Key Uncertainties in the Recent Air‐Sea Flux of CO2

Linking Global Changes of Snowfall and Wet-bulb Temperature

Gap filling of monthly temperature data and its effect on climatic variability and trends

How accurate are modern climate reanalyses for the data-sparse Tibetan Plateau region?

Analysis of total column CO2 and CH4 measurements in Berlin with WRF-GHG (open access)

Is deoxygenation detectable before warming in the thermocline? (open access)

Half a century of satellite remote sensing of sea-surface temperature

Remote sensing of glacier and ice sheet grounding lines: A review

Chaotic signature of climate extremes

HadUK‐Grid—A new UK dataset of gridded climate observations (open access)

Physical science of global warming

Revised estimates of paleoclimate sensitivity over the past 800,000 years

Warm Events Induce Loss of Resilience in Organic Carbon Production in the Northeast Pacific Ocean

Surface warming during the 2018/Mars Year 34 Global Dust Storm

Dynamics and thermodynamics of the mean Transpolar Drift and ice thickness in the Arctic Ocean

A missing component of Arctic warming: black carbon from gas flaring (open access)

Biology of the warming planet

Projecting marine species range shifts from only temperature can mask climate vulnerability

Secondary forest fragments offer important carbon‐biodiversity co‐benefits

Climate warming alters subsoil but not topsoil carbon dynamics in alpine grassland

Multiple stressor effects on coral reef ecosystems

Modeling the warming climate

Probing the Sources of Uncertainty in Transient Warming on Different Time‐Scales

Nonlinear response of extreme precipitation to warming in CESM1

Reproducing Internal Variability with Few Ensemble Runs

Climate projections for glacier change modelling over the Himalayas

Statistical downscaling to project extreme hourly precipitation over the UK

Humans deal with our warming the climate

The impact of climate change and variability on coffee production: a systematic review

The impact of temperature on mortality across different climate zones

Social preferences for distributive outcomes of climate policy

Does it matter if you “believe” in climate change? Not for coastal home vulnerability

Temperature and production efficiency growth: empirical evidence

The accuracy of German citizens’ confidence in their climate change knowledge

The future of agriculture and food: Evaluating the holistic costs and benefits

Evaluating China's water security for food production: The role of rainfall and irrigation

Characterization of Extreme Wet‐Bulb Temperature Events in Southern Pakistan

Global adaptation governance: An emerging but contested domain

Indigenous perceptions of climate anomalies in Malaysian Borneo

Valuation of nature and nature’s contributions to people (open access)

Rules to goals: emergence of new governance strategies for sustainable development (open access)

Urbanization and CO 2 emissions in resource-exhausted cities: evidence from Xuzhou city, China

The global cropland footprint of Denmark's food supply 2000–2013

Potentials and opportunities for low carbon energy transition in Vietnam: A policy analysis

Analysis of carbon tax efficiency in energy industries of selected EU countries

Carbon capture induced changes in Deccan basalt: a mass‐balance approach

Suggestions

Please let us know if you're aware of an article you think may be of interest for Skeptical Science research news, or if we've missed something that may be important. Send your input to Skeptical Science via our contact form.

The previous edition of Skeptical Science new research may be found here.

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/303wuwb

87 items this week, with 23 available as open access.

What are we doing on Mars?

We're from Earth, yet Included in this week's trawl of research articles are Streeter et al with Surface warming during the 2018/Mars Year 34 Global Dust Storm. Why are we visiting Mars today? Because the same storm that silenced the doughty Opportunity rover after over 14 years of operation yields an interesting research result on the dust-up's temporary effect on the Martian climate:

The impact of Mars’ 2018 Global Dust Storm (GDS) on surface and near‐surface air temperatures was investigated using an assimilation of Mars Climate Sounder (MCS) observations. Rather than simply resulting in cooling everywhere from solar absorption (average surface radiative flux fell 26 Wm‐2), the globally‐averaged result was a 0.9 K surface warming. These diurnally‐averaged surface temperature changes had a novel, highly non‐uniform spatial structure, with up to 16 K cooling/19 K warming. Net warming occurred in low thermal inertia (TI) regions, where rapid night‐time radiative cooling was compensated by increased longwave emission and scattering. This caused strong nightside warming, outweighing dayside cooling. The reduced surface‐air temperature gradient closely coupled surface and air temperatures, even causing local dayside air warming.

Note the similar causal mechanism and ultimate effect of increased surface temperatures to what a little additional CO2 in Earth's atmosphere produces. Despite a drastic reduction of surface energy delivery to Mars, night time temperatures rose and this effect was even true to some extent in day time.

Leaving aside dust not being gaseous, the principle and concerning difference between the two is that dust rapidly drops out of the atmosphere whether on Mars or at home, while the additional CO2 we've liberated into our local thin skin of gas will require several hundred years to find a permanent new home away from where it causes deleterious effects on our climate.

Lost in thought

It's continually surprising to see the almost laconic back-and-forth exploration of abstract economic matters as they apply to climate change, which to some of us seems to lack a sense of urgency or connection to the real world. Not to pick on them but simply as they appeared in this week's haul, as an example Mallapragada & Mignone bring us A theoretical basis for the equivalence between physical and economic climate metrics and implications for the choice of Global Warming Potential time horizon:

The global warming potential (GWP) is widely used in policy analysis, national greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting, and technology life cycle assessment (LCA) to compare the impact of non-CO2 GHG emissions to the impact of CO2 emissions. While the GWP is simple and versatile, different views about the appropriate choice of time horizon—and the factors that affect that choice—can impede decision-making. If the GWP is viewed as an approximation to a climate metric that more directly measures economic impact—the global damage potential (GDP)—then the time horizon may be viewed as a proxy for the discount rate. However, the validity of this equivalence rests on the theoretical basis used to equate the two metrics. In this paper, we develop a new theoretical basis for relating the GWP time horizon and the economic discount rate that avoids the most restrictive assumptions of prior studies, such as an assumed linear relationship between economic damages and temperature. We validate this approach with an extensive set of numerical experiments using an up-to-date climate emulator that represents state-dependent climate-carbon cycle feedbacks. The numerical results largely confirm the theoretical finding that, under certain reasonable assumptions, time horizons in the GWP of 100 years and 20 years are most consistent with discount rates of approximately 3% and 7% (or greater), respectively.

Introduction of the "discount rate" into thinking about climate change mitigation and adaptation costs and expenditures confuses simple and ignorant minds (such as the author of this blog entry). Application of a scrupulously calculated discount rate to the question of spending related to climate change is promised to yield a brighter future.To this layperson establishing this magic number appears to be a form of paralytic perfectionism and as well seems dependent on unreliable information about a future beyond our ken.

As a person who spends time on boats and yet fully intends to never fall overboard, I can spend a lot or a little on a "PFD" (personal flotation device) despite knowing full well that any such expenditure large or small will be much more productively employed in a true investment even at a very poor interest rate, per the advice of economic experts. The wisdom and promised benefits of not buying a PFD hold true until the exact moment when I pitch overboard into cold water and shortly am depending on the PFD for continued survival, at which point more riches in the future become crisply abstract. Surely if I'm dead I won't be able to grow my personal economy; staying alive appears to be a prime requirement for my successful economic outcome. Thus I choose to waste money now on a quality PFD despite it not being a rational choice in the formal economic sense.

Assuming we'll stay high and dry may drive the decision to not buy a PFD and instead invest elsewhere. Similarly, overweening fascination with and pursuit of establishing theoretically defensible discount rates in connection with climate change appears to hinge on a relatively static scenario of a functioning economy resembling to some degree what we've come to expect from the past: a machine producing more or less steady and uninterrupted growth. It seems arguable that assumptions required to model such an economy and produce an academically worthy and admirable result are not necessarily valid given the broadly agreed dire projections we face of global warming and its various knock-on disruptions; we're entering an era with challenges on a scale and breadth we've not yet encountered and so old rules may not apply.

What am I missing?

Ideally an actual economist would explain this in terms an ordinary layperson might understand. Coming up for air and offering some conclusions with clear directions based on the assumption we will be falling overboard and indeed have already lost our grip and footing— are clumsily plunging over the lifelines into a life-threatening circumstance— would be very helpful. Is there an argument for obtaining a PFD, the notionally irrational choice to spend money to buy some better luck, a wager to help assure a future?

Articles:

Observation of climate warming

Influence of instrumentation on long temperature time series

Key Uncertainties in the Recent Air‐Sea Flux of CO2

Linking Global Changes of Snowfall and Wet-bulb Temperature

Gap filling of monthly temperature data and its effect on climatic variability and trends

How accurate are modern climate reanalyses for the data-sparse Tibetan Plateau region?

Analysis of total column CO2 and CH4 measurements in Berlin with WRF-GHG (open access)

Is deoxygenation detectable before warming in the thermocline? (open access)

Half a century of satellite remote sensing of sea-surface temperature

Remote sensing of glacier and ice sheet grounding lines: A review

Chaotic signature of climate extremes

HadUK‐Grid—A new UK dataset of gridded climate observations (open access)

Physical science of global warming

Revised estimates of paleoclimate sensitivity over the past 800,000 years

Warm Events Induce Loss of Resilience in Organic Carbon Production in the Northeast Pacific Ocean

Surface warming during the 2018/Mars Year 34 Global Dust Storm

Dynamics and thermodynamics of the mean Transpolar Drift and ice thickness in the Arctic Ocean

A missing component of Arctic warming: black carbon from gas flaring (open access)

Biology of the warming planet

Projecting marine species range shifts from only temperature can mask climate vulnerability

Secondary forest fragments offer important carbon‐biodiversity co‐benefits

Climate warming alters subsoil but not topsoil carbon dynamics in alpine grassland

Multiple stressor effects on coral reef ecosystems

Modeling the warming climate

Probing the Sources of Uncertainty in Transient Warming on Different Time‐Scales

Nonlinear response of extreme precipitation to warming in CESM1

Reproducing Internal Variability with Few Ensemble Runs

Climate projections for glacier change modelling over the Himalayas

Statistical downscaling to project extreme hourly precipitation over the UK

Humans deal with our warming the climate

The impact of climate change and variability on coffee production: a systematic review

The impact of temperature on mortality across different climate zones

Social preferences for distributive outcomes of climate policy

Does it matter if you “believe” in climate change? Not for coastal home vulnerability

Temperature and production efficiency growth: empirical evidence

The accuracy of German citizens’ confidence in their climate change knowledge

The future of agriculture and food: Evaluating the holistic costs and benefits

Evaluating China's water security for food production: The role of rainfall and irrigation

Characterization of Extreme Wet‐Bulb Temperature Events in Southern Pakistan

Global adaptation governance: An emerging but contested domain

Indigenous perceptions of climate anomalies in Malaysian Borneo

Valuation of nature and nature’s contributions to people (open access)

Rules to goals: emergence of new governance strategies for sustainable development (open access)

Urbanization and CO 2 emissions in resource-exhausted cities: evidence from Xuzhou city, China

The global cropland footprint of Denmark's food supply 2000–2013

Potentials and opportunities for low carbon energy transition in Vietnam: A policy analysis

Analysis of carbon tax efficiency in energy industries of selected EU countries

Carbon capture induced changes in Deccan basalt: a mass‐balance approach

Suggestions

Please let us know if you're aware of an article you think may be of interest for Skeptical Science research news, or if we've missed something that may be important. Send your input to Skeptical Science via our contact form.

The previous edition of Skeptical Science new research may be found here.

from Skeptical Science https://ift.tt/303wuwb