When you hear astronomers speak of habitable worlds – or worlds in the habitable zone of their stars – do you think of alien civilizations? Or do you think of worlds where humans might someday live? What do astronomers mean by habitable? Perhaps not what you think.

To an astronomer, the word habitable simply means a planet whose physical conditions might allow life – any form of life, perhaps microbial life – to exist there. Here’s what NASA says about the word habitable:

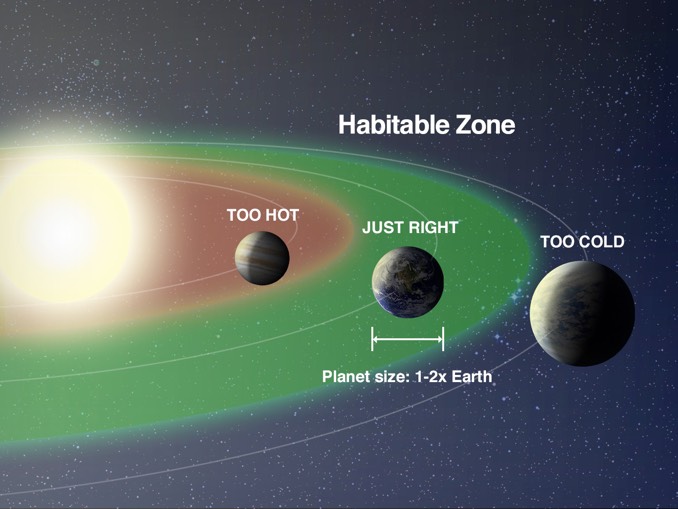

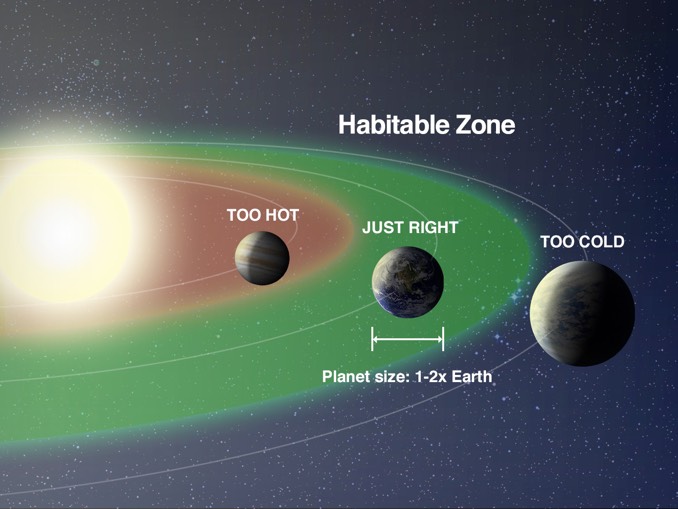

The standard definition for a habitable planet is one that can sustain life for a significant period. Based on our solar system, life requires liquid water, energy and nutrients. A ‘habitable zone’ is the region around a star where planets can receive the perfect amount of heat to maintain liquid water on their surfaces.

So our Earth, for example, is habitable. It’s the only planet in the habitable zone of our star, that is, the only one of our sun’s planets where liquid water can exist on the surface. So Earth has the right conditions for life: liquid water, energy, nutrients. Other worlds orbiting distant stars also lie in the habitable zones of their stars. But do they have liquid water … enough energy reaching the surface for living things to grow, thrive and produce nutrients? We don’t know for sure yet of any worlds like that, beyond Earth.

Habitable doesn’t mean inhabited

So it goes without saying that – so far – Earth is the only planet we know that’s inhabited. And it’s also the only planet we know, so far, where human life can walk around on the surface without spacesuits, breathing the air, drinking the water, eating the plants.

Then again, exoplanets – or planets orbiting distant sun – are not easy to find. As of late January 2024, we know only 5,572 confirmed exoplanets in 4,145 planetary systems, with 942 systems having more than one planet. Meanwhile, there are an estimated 100 to 400 billion stars in our home galaxy, the Milky Way.

So when we in the science media mention habitable exoplanets, please don’t think it means we’re suggesting that world might be an alternate Earth, or a world we might someday colonize. Far from it! Likewise, habitable doesn’t mean that astronomers believe alien life exists on this or that distant planet.

So why discuss habitability at all? The word has academic interest, certainly; professional astronomers are curious. And many in the public are curious also! We at EarthSky are curious. Aren’t you? Is Earth alone in the Milky Way galaxy, or are other worlds capable of supporting life as we know it? Those are big and weighty questions, and it’s exciting that astronomers are ferreting out the clues that might let us begin to answer them.

And sure. Maybe someday humans will venture to a habitable exoplanet. And maybe someday we will find life on a world orbiting the habitable zone of its star. But will this happen in our lifetimes? Will it ever happen?

Habitability in our solar system

Let’s look at our own solar system. We know Earth is habitable. But what about the other planets and moons? Some scientists think Venus may have been habitable in the past, but climate change turned it into the scorching furnace we know today. It also appears that Mars may have been more habitable in the past, when an ocean covered much of its surface. Even Mercury may have habitable spots, such as in its salt glaciers.

Farther out in the solar system, Saturn’s moon Enceladus is an exciting prospect for habitability. It’s covered in a global ocean hiding beneath an icy crust. Jupiter’s moon Europa may also have an ocean that could be habitable.

Habitable exoplanets

Many scientists are researching just what elements, abundances and combinations we should be looking for to find habitable exoplanets.

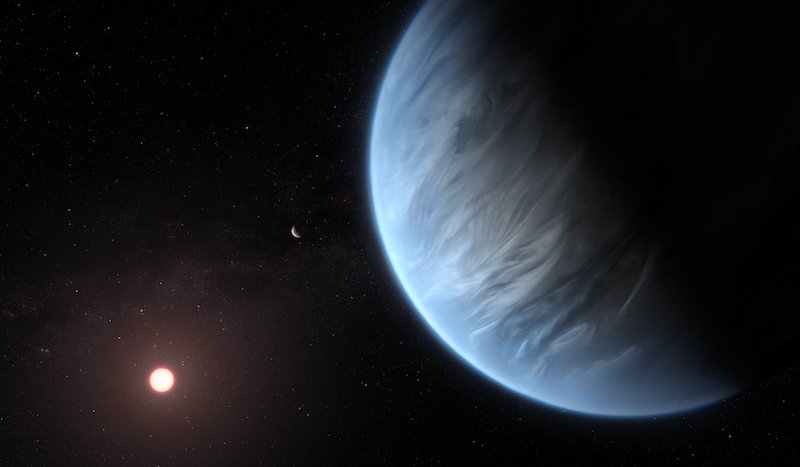

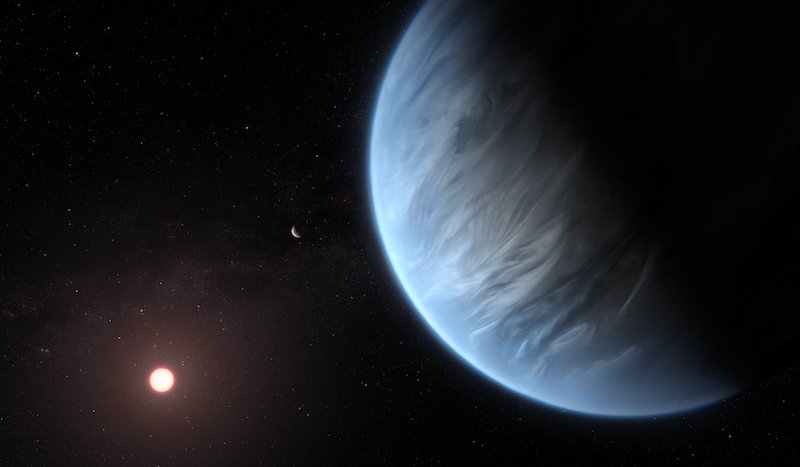

Some of the other key things scientists look for are terrestrial planets with the potential for water on their surfaces. Some of the candidate exoplanets for habitability include K2-18 b, which may have a deep hydrogen atmosphere and global water ocean. Another is Wolf 1069 b, an Earth-size and Earth-mass exoplanet orbiting in the habitable zone of its star just 31 light-years away.

Plans for a dedicated observatory

A proposed mission, called the Habitable Worlds Observatory, would help astronomers study exoplanets in habitable zones. In August 2023, scientists and engineers gathered at Caltech to discuss the future mission, which would launch in the late 2030s or early 2040s. The National Academy of Sciences’ Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics – a roadmap of upcoming astronomy goals – picked the Habitable Worlds Observatory as their top priority in 2020. The observatory would be second in power only to the James Webb Space Telescope.

Bottom line: When astronomers say a distant world is ‘habitable,’ what do they mean? Do they mean humans could live there? Do they mean we’ve discovered alien life? No to both. They simply mean that – on that distant world – the conditions are right for life, possibly just microbial life, to exist.

The post Here’s what ‘habitable’ means to astronomers first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/wG1qapT

When you hear astronomers speak of habitable worlds – or worlds in the habitable zone of their stars – do you think of alien civilizations? Or do you think of worlds where humans might someday live? What do astronomers mean by habitable? Perhaps not what you think.

To an astronomer, the word habitable simply means a planet whose physical conditions might allow life – any form of life, perhaps microbial life – to exist there. Here’s what NASA says about the word habitable:

The standard definition for a habitable planet is one that can sustain life for a significant period. Based on our solar system, life requires liquid water, energy and nutrients. A ‘habitable zone’ is the region around a star where planets can receive the perfect amount of heat to maintain liquid water on their surfaces.

So our Earth, for example, is habitable. It’s the only planet in the habitable zone of our star, that is, the only one of our sun’s planets where liquid water can exist on the surface. So Earth has the right conditions for life: liquid water, energy, nutrients. Other worlds orbiting distant stars also lie in the habitable zones of their stars. But do they have liquid water … enough energy reaching the surface for living things to grow, thrive and produce nutrients? We don’t know for sure yet of any worlds like that, beyond Earth.

Habitable doesn’t mean inhabited

So it goes without saying that – so far – Earth is the only planet we know that’s inhabited. And it’s also the only planet we know, so far, where human life can walk around on the surface without spacesuits, breathing the air, drinking the water, eating the plants.

Then again, exoplanets – or planets orbiting distant sun – are not easy to find. As of late January 2024, we know only 5,572 confirmed exoplanets in 4,145 planetary systems, with 942 systems having more than one planet. Meanwhile, there are an estimated 100 to 400 billion stars in our home galaxy, the Milky Way.

So when we in the science media mention habitable exoplanets, please don’t think it means we’re suggesting that world might be an alternate Earth, or a world we might someday colonize. Far from it! Likewise, habitable doesn’t mean that astronomers believe alien life exists on this or that distant planet.

So why discuss habitability at all? The word has academic interest, certainly; professional astronomers are curious. And many in the public are curious also! We at EarthSky are curious. Aren’t you? Is Earth alone in the Milky Way galaxy, or are other worlds capable of supporting life as we know it? Those are big and weighty questions, and it’s exciting that astronomers are ferreting out the clues that might let us begin to answer them.

And sure. Maybe someday humans will venture to a habitable exoplanet. And maybe someday we will find life on a world orbiting the habitable zone of its star. But will this happen in our lifetimes? Will it ever happen?

Habitability in our solar system

Let’s look at our own solar system. We know Earth is habitable. But what about the other planets and moons? Some scientists think Venus may have been habitable in the past, but climate change turned it into the scorching furnace we know today. It also appears that Mars may have been more habitable in the past, when an ocean covered much of its surface. Even Mercury may have habitable spots, such as in its salt glaciers.

Farther out in the solar system, Saturn’s moon Enceladus is an exciting prospect for habitability. It’s covered in a global ocean hiding beneath an icy crust. Jupiter’s moon Europa may also have an ocean that could be habitable.

Habitable exoplanets

Many scientists are researching just what elements, abundances and combinations we should be looking for to find habitable exoplanets.

Some of the other key things scientists look for are terrestrial planets with the potential for water on their surfaces. Some of the candidate exoplanets for habitability include K2-18 b, which may have a deep hydrogen atmosphere and global water ocean. Another is Wolf 1069 b, an Earth-size and Earth-mass exoplanet orbiting in the habitable zone of its star just 31 light-years away.

Plans for a dedicated observatory

A proposed mission, called the Habitable Worlds Observatory, would help astronomers study exoplanets in habitable zones. In August 2023, scientists and engineers gathered at Caltech to discuss the future mission, which would launch in the late 2030s or early 2040s. The National Academy of Sciences’ Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics – a roadmap of upcoming astronomy goals – picked the Habitable Worlds Observatory as their top priority in 2020. The observatory would be second in power only to the James Webb Space Telescope.

Bottom line: When astronomers say a distant world is ‘habitable,’ what do they mean? Do they mean humans could live there? Do they mean we’ve discovered alien life? No to both. They simply mean that – on that distant world – the conditions are right for life, possibly just microbial life, to exist.

The post Here’s what ‘habitable’ means to astronomers first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/wG1qapT

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire