30 days of terror for the Webb

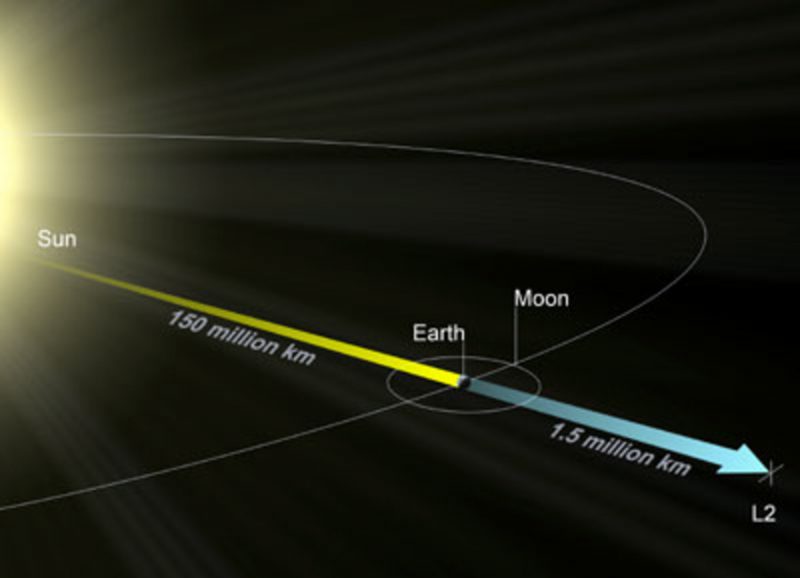

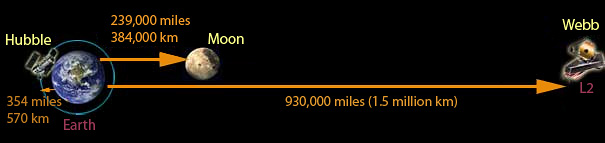

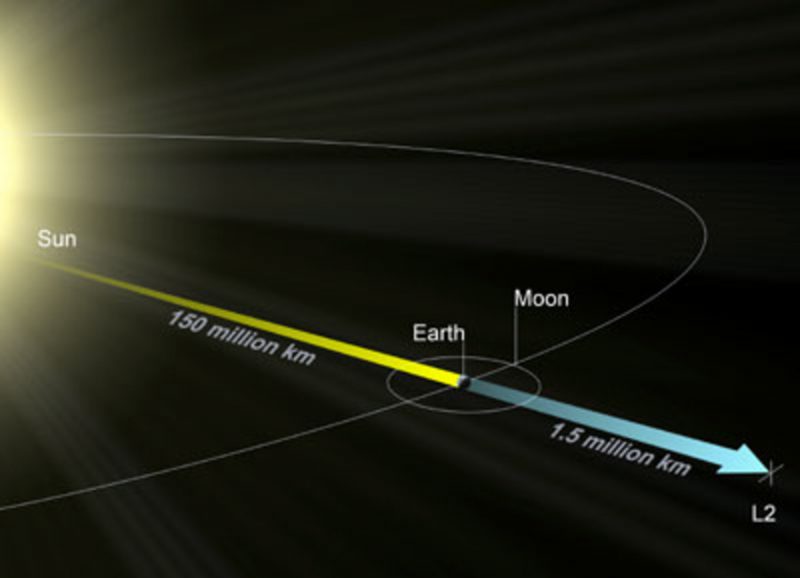

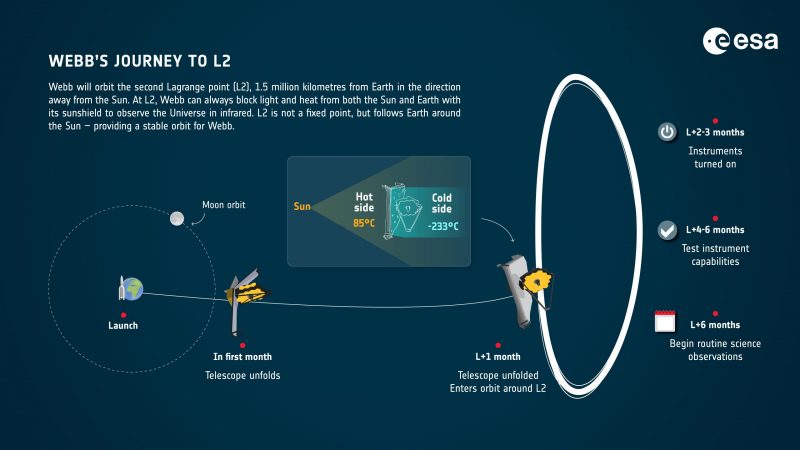

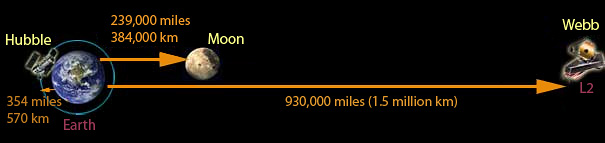

The James Webb Space Telescope is on its way to L2, following a successful launch on December 25, 2021. Astronomers following plans for the launch agree: it was a relief to see the $9.7-billion space telescope go up at last. After all, this telescope – the most complicated ever built – has been under development for decades. And the hopes and dreams of astronomers are pinned upon it. But the launch was just the beginning. Unlike the Hubble Space Telescope and thousands of other satellites, the Webb won’t orbit Earth. Webb is now journeying to Lagrangian point 2, aka L2, which is almost 1 million miles (1.5 million km) behind Earth as viewed from the sun … or about four times the moon’s distance. It’ll take the Webb about a month to reach L2. And, during its journey, the massive telescope isn’t remaining snug in its packaging. It’ll be slowly unfolding into its final configuration, with hundreds of moving pieces that have to operate exactly as designed. Clearly, something might go wrong. And that’s why many are jokingly calling the month after launch 30 days of terror for the Webb.

Why L2, and where is it?

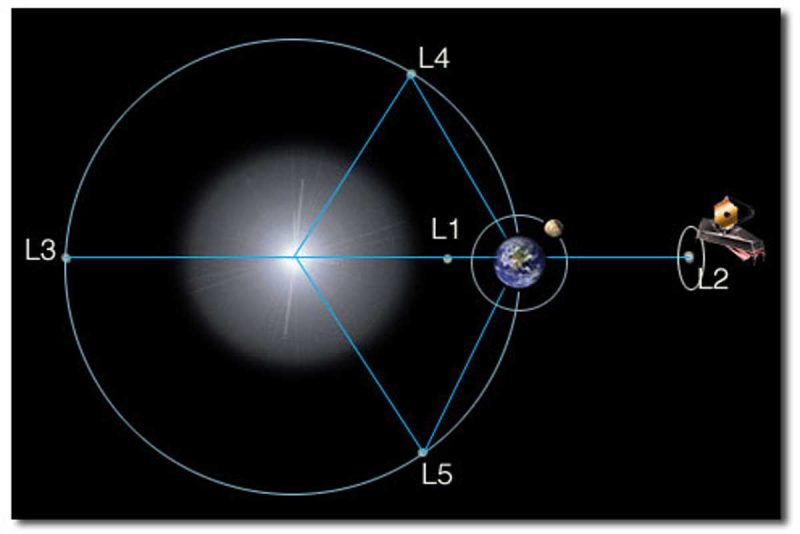

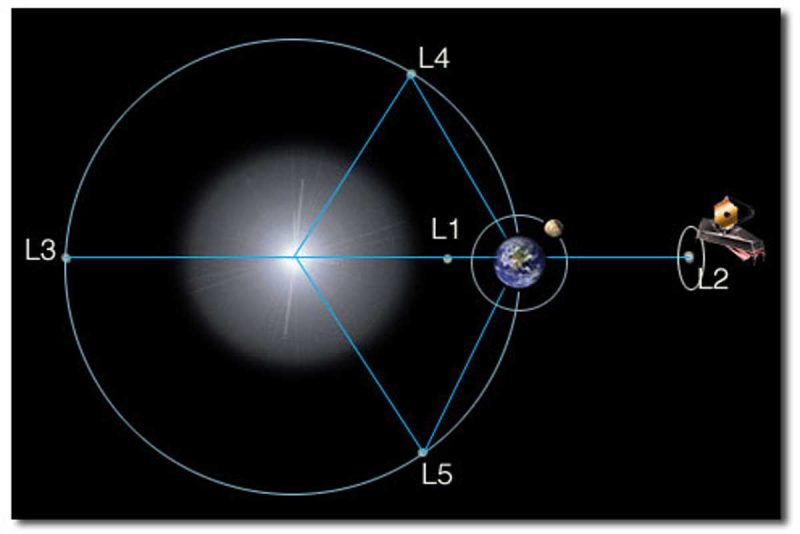

Why is the Webb going to a point so far away? This point in space – the second Lagrangian point – is where, in the Earth-sun system, gravitational forces and a body’s orbital motion balance each other. So a spacecraft can “hover” relatively easily at L2. It can stay near Earth, while both Earth and the spacecraft orbit the sun. In fact, the European Space Agency (ESA) has called L2 “a preeminent location for advanced space probes.” Other notable space observatories orbit or will orbit the sun at L2, including ESA’s redoubtable Gaia spacecraft, which has made so many fascinating discoveries about our Milky Way galaxy. Other ESA missions, including Herschel, Planck, Eddington and Darwin – also orbit or will go to L2.

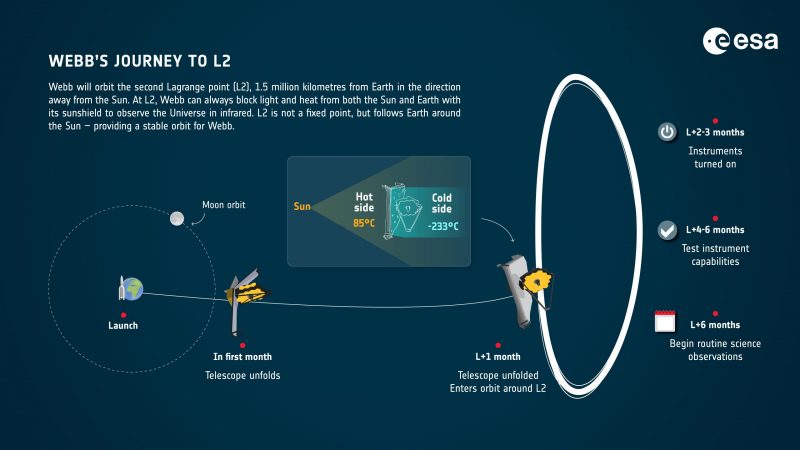

For the Webb, another advantage of L2 is that it’s a step farther away from the heat of the sun and Earth. Satellites in Earth orbit – for example, the International Space Station or the Hubble Space Telescope – undergo temperature changes about every 90 minutes, depending on whether the satellite’s surface is Earth’s shadow or on the side of Earth closest to the sun. At L2, Webb won’t undergo this same temperature-shifting effect, which has the potential to create distortions in the telescope’s ability to view the universe. The Webb will observe primarily infrared light coming from faint and very distant objects. In order to be able to detect those faint signals, the telescope itself must be kept extremely cold: -370 F (220 C) or lower. That’s why the Webb has a five-layer, tennis-court-sized sunshield, to protect the telescope from the heat of the sun and keep its instruments cold.

Recalling Hubble’s rescue mission

But the huge sunshield is one of Webb’s components that will be unfolding over the coming month. And L2 is far away.

Perhaps you recall that – after the Hubble Space Telescope’s launch in 1990 – operators realized there was an aberration in the space telescope’s primary mirror. The problem affected the clarity of the telescope’s early images. NASA explained:

Replacing the [Hubble] mirror was not practical, so the best solution was to build replacement instruments that fixed the flaw much the same way a pair of glasses correct the vision of a near-sighted person. The corrective optics and new instruments were built and installed on Hubble by spacewalking astronauts during a shuttle mission in 1993.

And so, thanks to that rescue mission by astronauts, Hubble was able to fulfill its mission.

If something goes wrong and a part needs adjusting on the Webb, as happened with Hubble, we’ll have no easy option for sending astronauts to fix the problem. Indeed, earthly astronauts have never traveled to the L2 point in the Earth-sun system.

30 days of terror

Following its launch by an Ariane 5 rocket on December 25, 2021, Webb’s first task will come just 30 minutes later. It will deploy its solar array to stop draining battery power. Next, about two hours after launch, it will deploy its high-gain antenna. From then on, it should be able to communicate with Earth.

Between days three and seven, Webb will deploy the parts of its sunshield, raise the tower assembly and deploy the momentum flap. Day 10 might be the most nail-biting, as Webb hoists its secondary mirror into position. Heidi Hammel, a scientist on the mission, said:

For me, personally, that’s the scariest part of the whole deployment sequence, the secondary mirror … If we don’t have a secondary mirror, we don’t get any light from space into our cameras and spectrographs. There’s nothing.

The rest of the mirror will unfurl by the end of the second week. Then, on day 29, the Webb will fire its thrusters to enter orbit. After those first 30 days, testing will begin. Because Webb’s primary mirror is three times larger than Hubble’s, it had to be made of 18 individual segments so it could be folded for launch. Those 18 segments will all need to be recalibrated (aligned), which will take about 10 days. A week of alignment followed by weeks of testing mean that the telescope won’t be ready for scientific operations for about six months.

Webb vs. Hubble

The first images from Webb should be available by summer 2022. Because Webb is an infrared telescope, its focus will be spectroscopy. Hubble provided images in visible light. The advantage of infrared is that Webb will be able to look farther into the universe than ever before. NASA gave a great visualization of the power of Webb to look into the past during a Q&A session on Reddit:

Imagine all of time, from the beginning of the universe until now, is represented on a year-long calendar. If right now is December 31 at 11:55 pm, Webb will be able to see all the way back to January 6th.

NASA also explained why scientists want to see in the infrared and use spectroscopy. Spectroscopy allows astronomers to:

understand what is there, not just how it looks.

When a Reddit user asked if Webb was going to reproduce the famous Hubble Ultra Deep Field photo, NASA said:

Webb will observe the Ultra Deep Field in our first year of science operations. It’ll take Webb less than a day to see deeper than Hubble saw in two weeks of staring. Webb is going to go much deeper, finding tens of thousand of galaxies that are too red and too faint for Hubble to detect.

While we’ve all been wowed and moved for decades by what the Hubble Space Telescope has shown us of the universe, we expect to be further blown away by the images and revelations of Hubble’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope.

But first, we have to get through the next 30 days of terror.

Bottom line: The James Webb Space Telescope will take about a month to unfurl as it travels to L2. Some are calling this nail-biting time interval the Webb’s 30 days of terror.

The post Now, for James Webb Space Telescope, ’30 days of terror’ first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3FuVjXp

30 days of terror for the Webb

The James Webb Space Telescope is on its way to L2, following a successful launch on December 25, 2021. Astronomers following plans for the launch agree: it was a relief to see the $9.7-billion space telescope go up at last. After all, this telescope – the most complicated ever built – has been under development for decades. And the hopes and dreams of astronomers are pinned upon it. But the launch was just the beginning. Unlike the Hubble Space Telescope and thousands of other satellites, the Webb won’t orbit Earth. Webb is now journeying to Lagrangian point 2, aka L2, which is almost 1 million miles (1.5 million km) behind Earth as viewed from the sun … or about four times the moon’s distance. It’ll take the Webb about a month to reach L2. And, during its journey, the massive telescope isn’t remaining snug in its packaging. It’ll be slowly unfolding into its final configuration, with hundreds of moving pieces that have to operate exactly as designed. Clearly, something might go wrong. And that’s why many are jokingly calling the month after launch 30 days of terror for the Webb.

Why L2, and where is it?

Why is the Webb going to a point so far away? This point in space – the second Lagrangian point – is where, in the Earth-sun system, gravitational forces and a body’s orbital motion balance each other. So a spacecraft can “hover” relatively easily at L2. It can stay near Earth, while both Earth and the spacecraft orbit the sun. In fact, the European Space Agency (ESA) has called L2 “a preeminent location for advanced space probes.” Other notable space observatories orbit or will orbit the sun at L2, including ESA’s redoubtable Gaia spacecraft, which has made so many fascinating discoveries about our Milky Way galaxy. Other ESA missions, including Herschel, Planck, Eddington and Darwin – also orbit or will go to L2.

For the Webb, another advantage of L2 is that it’s a step farther away from the heat of the sun and Earth. Satellites in Earth orbit – for example, the International Space Station or the Hubble Space Telescope – undergo temperature changes about every 90 minutes, depending on whether the satellite’s surface is Earth’s shadow or on the side of Earth closest to the sun. At L2, Webb won’t undergo this same temperature-shifting effect, which has the potential to create distortions in the telescope’s ability to view the universe. The Webb will observe primarily infrared light coming from faint and very distant objects. In order to be able to detect those faint signals, the telescope itself must be kept extremely cold: -370 F (220 C) or lower. That’s why the Webb has a five-layer, tennis-court-sized sunshield, to protect the telescope from the heat of the sun and keep its instruments cold.

Recalling Hubble’s rescue mission

But the huge sunshield is one of Webb’s components that will be unfolding over the coming month. And L2 is far away.

Perhaps you recall that – after the Hubble Space Telescope’s launch in 1990 – operators realized there was an aberration in the space telescope’s primary mirror. The problem affected the clarity of the telescope’s early images. NASA explained:

Replacing the [Hubble] mirror was not practical, so the best solution was to build replacement instruments that fixed the flaw much the same way a pair of glasses correct the vision of a near-sighted person. The corrective optics and new instruments were built and installed on Hubble by spacewalking astronauts during a shuttle mission in 1993.

And so, thanks to that rescue mission by astronauts, Hubble was able to fulfill its mission.

If something goes wrong and a part needs adjusting on the Webb, as happened with Hubble, we’ll have no easy option for sending astronauts to fix the problem. Indeed, earthly astronauts have never traveled to the L2 point in the Earth-sun system.

30 days of terror

Following its launch by an Ariane 5 rocket on December 25, 2021, Webb’s first task will come just 30 minutes later. It will deploy its solar array to stop draining battery power. Next, about two hours after launch, it will deploy its high-gain antenna. From then on, it should be able to communicate with Earth.

Between days three and seven, Webb will deploy the parts of its sunshield, raise the tower assembly and deploy the momentum flap. Day 10 might be the most nail-biting, as Webb hoists its secondary mirror into position. Heidi Hammel, a scientist on the mission, said:

For me, personally, that’s the scariest part of the whole deployment sequence, the secondary mirror … If we don’t have a secondary mirror, we don’t get any light from space into our cameras and spectrographs. There’s nothing.

The rest of the mirror will unfurl by the end of the second week. Then, on day 29, the Webb will fire its thrusters to enter orbit. After those first 30 days, testing will begin. Because Webb’s primary mirror is three times larger than Hubble’s, it had to be made of 18 individual segments so it could be folded for launch. Those 18 segments will all need to be recalibrated (aligned), which will take about 10 days. A week of alignment followed by weeks of testing mean that the telescope won’t be ready for scientific operations for about six months.

Webb vs. Hubble

The first images from Webb should be available by summer 2022. Because Webb is an infrared telescope, its focus will be spectroscopy. Hubble provided images in visible light. The advantage of infrared is that Webb will be able to look farther into the universe than ever before. NASA gave a great visualization of the power of Webb to look into the past during a Q&A session on Reddit:

Imagine all of time, from the beginning of the universe until now, is represented on a year-long calendar. If right now is December 31 at 11:55 pm, Webb will be able to see all the way back to January 6th.

NASA also explained why scientists want to see in the infrared and use spectroscopy. Spectroscopy allows astronomers to:

understand what is there, not just how it looks.

When a Reddit user asked if Webb was going to reproduce the famous Hubble Ultra Deep Field photo, NASA said:

Webb will observe the Ultra Deep Field in our first year of science operations. It’ll take Webb less than a day to see deeper than Hubble saw in two weeks of staring. Webb is going to go much deeper, finding tens of thousand of galaxies that are too red and too faint for Hubble to detect.

While we’ve all been wowed and moved for decades by what the Hubble Space Telescope has shown us of the universe, we expect to be further blown away by the images and revelations of Hubble’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope.

But first, we have to get through the next 30 days of terror.

Bottom line: The James Webb Space Telescope will take about a month to unfurl as it travels to L2. Some are calling this nail-biting time interval the Webb’s 30 days of terror.

The post Now, for James Webb Space Telescope, ’30 days of terror’ first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3FuVjXp

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire