The fate of Arctic sea ice

In our warming world, the extent of summertime sea ice in the Arctic is shrinking. It’s less than half of what it was in the 1980s. And rapid Arctic sea ice decline is ongoing. Will some of us alive today live to see an ice-free Arctic in the summertime? Scientists at Columbia University in New York said this month (October 12, 2021) that their new projections indicate a daunting future for Arctic sea ice.

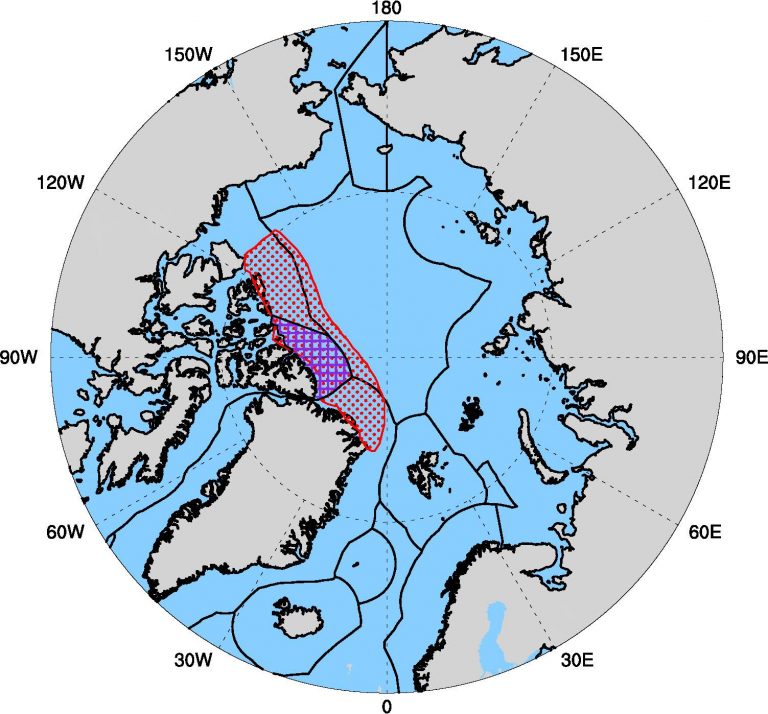

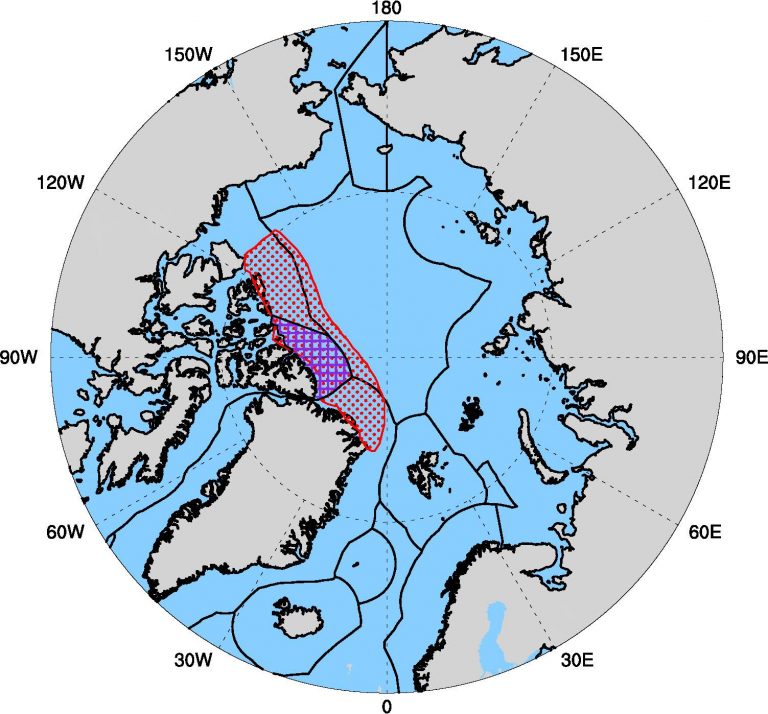

The new work suggests a region called the Last Ice Area – north of Greenland and the Canadian Archipelago, where ice is normally thickest – is teetering. Optimistic scenarios show that, at best, the ice will dramatically thin by the end of this century. And pessimistic scenarios show summertime sea ice in the Arctic will disappear by 2100, along with the animals, such as seals and polar bears, that depend on it.

The peer-reviewed journal Earth’s Future published these scientists’ study on September 2.

Co-author Robert Newton of Columbia University used the word “experiment” to describe Earth’s climate – and the repercussions of global warming – in the Arctic:

Unfortunately, this is a massive experiment we’re doing. If the year-round ice goes away, entire ice-dependent ecosystems will collapse, and something new will begin.

The Last Ice Area

The scientists’ study looked at a 1-million-square-kilometer (about 400,000-square-mile) region north of Greenland and the coasts of the Canadian Archipelago. Earlier researchers had deemed this refuge the Last Ice area, because traditionally the ice has been thickest in this region. It’s the part of the Arctic that scientists see as summer ice’s last stand.

When the North Pole tilts away from the sun and the Northern Hemisphere returns to winter, the Arctic Ocean generally freezes over after its balmy summers. Scientists expect winter ice to continue to form for some time.

The ice in the Last Ice Area can grow up to a meter thick each winter. Summer brings open water to some areas, which helps winds and currents carry floating ice. Most of the ice that winds up in the Last Ice Area comes from continental shelves off Siberia via the transpolar drift, a major current in the Arctic Ocean. Inflows of ice have built ridges up to 10 meters high, which can last for 10 years or more, in the Last Ice Area.

A rich marine ecosystem

Multiyear ice in the Last Ice Area creates a rich marine ecosystem. Algae blooms into thick mats at the edges and bottoms of the sea ice. This is the basis of the region’s food chain. Tiny animals live in the mats of algae. These animals feed fish. Fish feed the seals. Seals feed the polar bears.

Beyond food sources, the thick, jumbled ice provides lairs for seals and caves for polar bears to raise their young. The challenging icescape also makes it difficult for humans to encroach on the animals’ territory.

Less ice to go around

As the world warms, ice that forms is thinner and melts faster. There will be less ice in the Arctic Ocean in general, and therefore less ice to drift across the sea and accumulate in the Last Ice Area. As the scientists said:

This will starve the Last Ice Area in the next few decades. Some ice will continue to drift in from the central Arctic, and some will form locally, but neither will be enough to maintain current conditions.

In the optimistic scenario where globally we achieve lower emissions, scientists believe summer ice in the Last Ice Area will remain, but just a meter thick. This will still allow some of the Arctic animals to survive. In the pessimistic scenario, under continued high emissions, by 2100 there will be no summer ice anywhere in the Arctic Ocean. Newton described what the new environment may entail:

This is not to say it will be a barren, lifeless environment. New things will emerge, but it may take some time for new creatures to invade.

One stumbling block for life from farther south to take up residence in the north is that those plants that rely on photosynthesis will still be faced with long, dark months above the Arctic Circle.

Looking for the positive

The scientists said that if we can achieve lower emissions in the 21st century, the region may be able to cling to life until the temperatures start dropping again. One positive step in the Last Ice Area is that in 2019 Canada established the 125,000-square-mile (320,000-square-km) Tuvaijuittuq Marine Protected Area. The protected area covers a third of the Last Ice Area and lies in the Inuit territory of Nunavut.

The protections include a ban on mining, transportation and other developments. These protections are only in place for five years, while Canada considers permanent protection.

Pressure on Arctic areas

As the ice melts in the Arctic, access opens up to areas that before were challenging for digging, drilling and shipping. More marine protected areas will be needed to save the Last Ice Area from the increased pressure and potential pollution associated with these activities. The scientists argue that:

Now is the time for local communities, the Arctic nations and the international community to develop governance and institutional structures supportive of sustainable ice shed management.

Bottom line: Our warming world means the fate of Arctic sea ice could be in peril, along with the plants, animals and rich ecosystem that call it home.

Source: Defining the “Ice Shed” of the Arctic Ocean’s Last Ice Area and Its Future Evolution

The post The fate of Arctic sea ice first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3Bkpbmy

The fate of Arctic sea ice

In our warming world, the extent of summertime sea ice in the Arctic is shrinking. It’s less than half of what it was in the 1980s. And rapid Arctic sea ice decline is ongoing. Will some of us alive today live to see an ice-free Arctic in the summertime? Scientists at Columbia University in New York said this month (October 12, 2021) that their new projections indicate a daunting future for Arctic sea ice.

The new work suggests a region called the Last Ice Area – north of Greenland and the Canadian Archipelago, where ice is normally thickest – is teetering. Optimistic scenarios show that, at best, the ice will dramatically thin by the end of this century. And pessimistic scenarios show summertime sea ice in the Arctic will disappear by 2100, along with the animals, such as seals and polar bears, that depend on it.

The peer-reviewed journal Earth’s Future published these scientists’ study on September 2.

Co-author Robert Newton of Columbia University used the word “experiment” to describe Earth’s climate – and the repercussions of global warming – in the Arctic:

Unfortunately, this is a massive experiment we’re doing. If the year-round ice goes away, entire ice-dependent ecosystems will collapse, and something new will begin.

The Last Ice Area

The scientists’ study looked at a 1-million-square-kilometer (about 400,000-square-mile) region north of Greenland and the coasts of the Canadian Archipelago. Earlier researchers had deemed this refuge the Last Ice area, because traditionally the ice has been thickest in this region. It’s the part of the Arctic that scientists see as summer ice’s last stand.

When the North Pole tilts away from the sun and the Northern Hemisphere returns to winter, the Arctic Ocean generally freezes over after its balmy summers. Scientists expect winter ice to continue to form for some time.

The ice in the Last Ice Area can grow up to a meter thick each winter. Summer brings open water to some areas, which helps winds and currents carry floating ice. Most of the ice that winds up in the Last Ice Area comes from continental shelves off Siberia via the transpolar drift, a major current in the Arctic Ocean. Inflows of ice have built ridges up to 10 meters high, which can last for 10 years or more, in the Last Ice Area.

A rich marine ecosystem

Multiyear ice in the Last Ice Area creates a rich marine ecosystem. Algae blooms into thick mats at the edges and bottoms of the sea ice. This is the basis of the region’s food chain. Tiny animals live in the mats of algae. These animals feed fish. Fish feed the seals. Seals feed the polar bears.

Beyond food sources, the thick, jumbled ice provides lairs for seals and caves for polar bears to raise their young. The challenging icescape also makes it difficult for humans to encroach on the animals’ territory.

Less ice to go around

As the world warms, ice that forms is thinner and melts faster. There will be less ice in the Arctic Ocean in general, and therefore less ice to drift across the sea and accumulate in the Last Ice Area. As the scientists said:

This will starve the Last Ice Area in the next few decades. Some ice will continue to drift in from the central Arctic, and some will form locally, but neither will be enough to maintain current conditions.

In the optimistic scenario where globally we achieve lower emissions, scientists believe summer ice in the Last Ice Area will remain, but just a meter thick. This will still allow some of the Arctic animals to survive. In the pessimistic scenario, under continued high emissions, by 2100 there will be no summer ice anywhere in the Arctic Ocean. Newton described what the new environment may entail:

This is not to say it will be a barren, lifeless environment. New things will emerge, but it may take some time for new creatures to invade.

One stumbling block for life from farther south to take up residence in the north is that those plants that rely on photosynthesis will still be faced with long, dark months above the Arctic Circle.

Looking for the positive

The scientists said that if we can achieve lower emissions in the 21st century, the region may be able to cling to life until the temperatures start dropping again. One positive step in the Last Ice Area is that in 2019 Canada established the 125,000-square-mile (320,000-square-km) Tuvaijuittuq Marine Protected Area. The protected area covers a third of the Last Ice Area and lies in the Inuit territory of Nunavut.

The protections include a ban on mining, transportation and other developments. These protections are only in place for five years, while Canada considers permanent protection.

Pressure on Arctic areas

As the ice melts in the Arctic, access opens up to areas that before were challenging for digging, drilling and shipping. More marine protected areas will be needed to save the Last Ice Area from the increased pressure and potential pollution associated with these activities. The scientists argue that:

Now is the time for local communities, the Arctic nations and the international community to develop governance and institutional structures supportive of sustainable ice shed management.

Bottom line: Our warming world means the fate of Arctic sea ice could be in peril, along with the plants, animals and rich ecosystem that call it home.

Source: Defining the “Ice Shed” of the Arctic Ocean’s Last Ice Area and Its Future Evolution

The post The fate of Arctic sea ice first appeared on EarthSky.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3Bkpbmy

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire