A 10,000-pixel MKID photon detector, part of the new technology being developed to help directly image distant exoplanets. Image via Ben Mazin/ UC Santa Barbara.

Over 4,000 exoplanets – planets orbiting other stars – have been discovered so far, with thousands more expected in the near future. These worlds are very far away, and only a very few have actually been glimpsed in images to date; those that we’ve seen look like tiny pinpoints next to their stars. But now new technology for imaging exoplanets is being developed by UC Santa Barbara and the Heising-Simons Foundation. Some of these planets may be potentially habitable, making them the most exciting targets for direct imaging.

The promising news was announced by UC Santa Barbara on March 18, 2020.

There are various methods to find exoplanets. Most exoplanets have been found by the tiny gravitational effects they have on their stars, or by measuring the amount of light they block when they transit in front of their stars. Even then, that is a difficult, painstaking task. So far, most of the planets found have been giants, like Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus or Neptune, that are close to their stars, since they are the easiest to detect. Simply, bigger planets are easier to find than smaller ones. Only more recently have we started finding smaller rocky worlds, including ones in the habitable zones of their stars. The habitable zone is where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist on planetary surfaces, although that is by no means guaranteed. Compared to stars, planets are so small and faint that their light gets washed out by the glare from their stars.

What scientists really want to be able to do more is photograph more exoplanets directly; not just the big ones, but especially ones that are similar to Earth in size, in the habitable zones of their stars. As Benjamin Mazin, whose lab is leading UC Santa Barbara’s part of the effort, said in a statement:

As a result of this observational bias, there are very few examples of detected Earth-like planets.

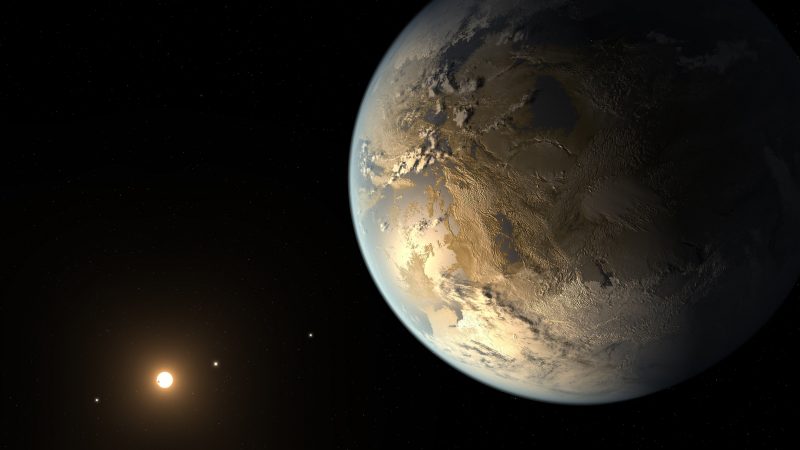

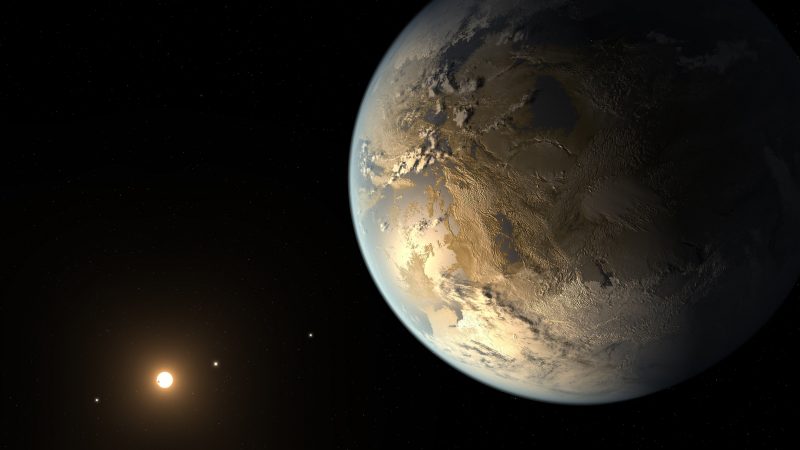

Artist’s conception of Kepler-186f, the first Earth-sized exoplanet discovered orbiting in the habitable zone of its star. The new technology being developed could enable scientists to finally directly image some of these worlds and determine whether they are actually habitable or not. Image via NASA Ames/ JPL-Caltech/ T. Pyle/ Phys.org.

How exciting would it be to finally see worlds that may be similar to Earth in some ways?

But seeing them is only part of what makes this so important. By doing so, researchers could more easily analyze the light from these worlds and search for possible biosignatures in their atmospheres, gases that could be produced by life, such as oxygen or methane. Mazin said:

Measuring the atmospheric composition of rocky exoplanets for biosignatures calls for a new observational method.

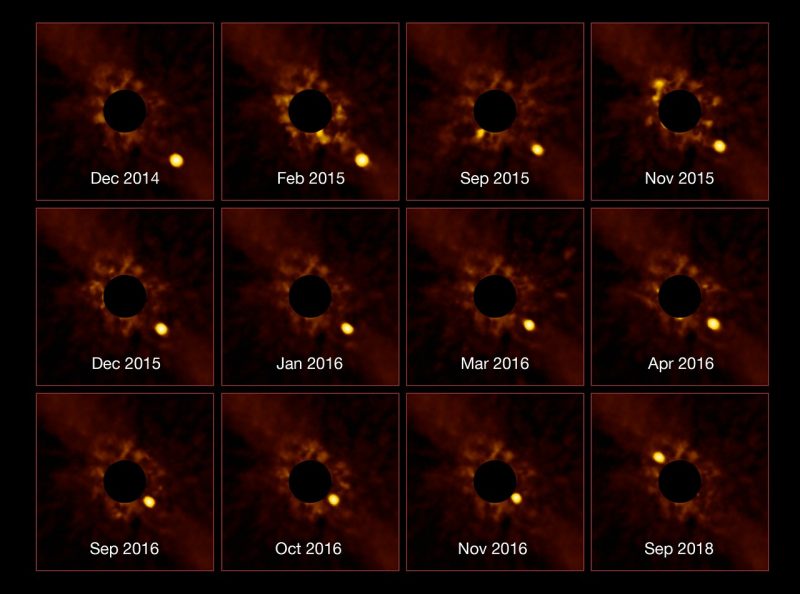

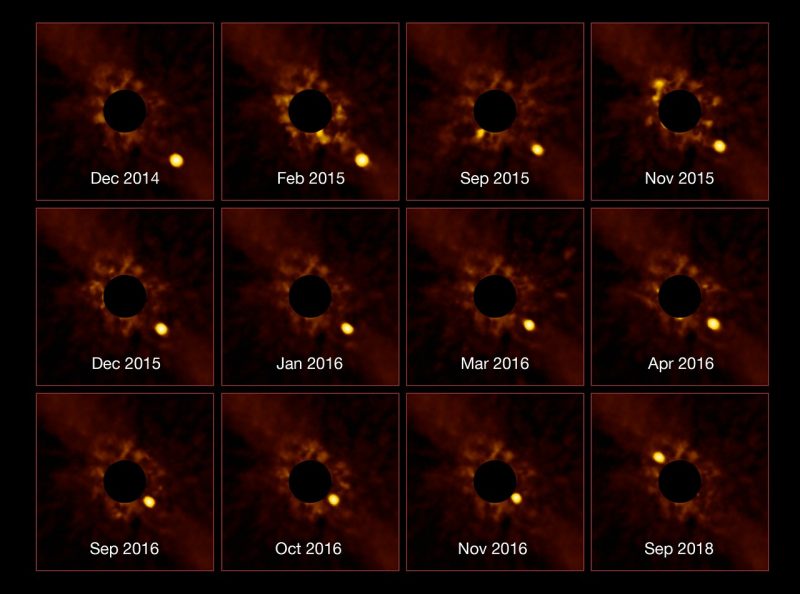

Beta Pictoris b is one of the few exoplanets that scientists have been able to photograph so far. This series of images from ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) shows it orbiting its star. Beta Pictoris b is still a young, hot planet, making it easier to directly image. Image via ESO/ Lagrange/ SPHERE consortium.

Scientists could measure the chemical composition of the planet’s atmosphere by using spectroscopy. In this way, the light passing through the planet’s atmosphere can be broken down into its individual colors. Different colors indicate what kinds of chemicals are present in the atmosphere. This has already been done to some extent before, but only for large gas giant type exoplanets. Having actual images of exoplanets would make it easier to study them. Mazin said:

Taking a picture of a nearby solar system is one of the most technologically challenging things we do in astronomy, mainly because Earth’s atmosphere royally messes up the picture. It’s like trying to take a picture through a windshield that’s getting blasted with rain.

While this technology can be used for a variety of different exoplanets, the primary goal is to be able to characterize Earth-sized planets with temperate conditions that could be habitable. We already know of a growing number of such worlds in the habitable zones of their stars, but other factors can affect a planet’s potential habitability, like the composition of its atmosphere, how much radiation it receives from its star, amount of water, etc.

Mazin’s lab is just one of multiple teams of university astronomers that the Heising-Simons Foundation is investing in. This will advance the technology needed to image these kinds of worlds and learn more about their potential habitability.

Benjamin Mazin at UC Santa Barbara, whose lab is helping develop new technology to directly image exoplanets. Image via UC Santa Barbara.

Another key piece of technology being developed by UC Santa Barbara is a new kind of superconducting photon detector called a microwave kinetic inductance detector (MKID), which has been integrated with the 8-meter (26-foot) Subaru Telescope in Hawaii. This also uses Heising-Simons Foundation funding to develop the necessary data processing algorithms. Mazin said:

I feel there is no more compelling problem to work on. Learning about nearby planets tells us a lot about ourselves and our place in the universe.

Only a handful of exoplanets have been directly imaged to date, such as the young, hot giant planet Beta Pictoris b, 63 light-years away. But with this new technology, scientists should now be able to photograph many more distant worlds. While they still won’t look like much more than just bright dots given their extreme distances from us, just being able to see them at all, and better analyze their atmospheres, will be a huge accomplishment. Then, we will be a big step closer to finding potentially habitable worlds that may be similar to ours, and, perhaps, discovering the first evidence of life in an alien solar system.

Bottom line: Researchers at UC Santa Barbara are helping to develop new technology to directly image potentially habitable exoplanets.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2UmpHhL

A 10,000-pixel MKID photon detector, part of the new technology being developed to help directly image distant exoplanets. Image via Ben Mazin/ UC Santa Barbara.

Over 4,000 exoplanets – planets orbiting other stars – have been discovered so far, with thousands more expected in the near future. These worlds are very far away, and only a very few have actually been glimpsed in images to date; those that we’ve seen look like tiny pinpoints next to their stars. But now new technology for imaging exoplanets is being developed by UC Santa Barbara and the Heising-Simons Foundation. Some of these planets may be potentially habitable, making them the most exciting targets for direct imaging.

The promising news was announced by UC Santa Barbara on March 18, 2020.

There are various methods to find exoplanets. Most exoplanets have been found by the tiny gravitational effects they have on their stars, or by measuring the amount of light they block when they transit in front of their stars. Even then, that is a difficult, painstaking task. So far, most of the planets found have been giants, like Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus or Neptune, that are close to their stars, since they are the easiest to detect. Simply, bigger planets are easier to find than smaller ones. Only more recently have we started finding smaller rocky worlds, including ones in the habitable zones of their stars. The habitable zone is where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist on planetary surfaces, although that is by no means guaranteed. Compared to stars, planets are so small and faint that their light gets washed out by the glare from their stars.

What scientists really want to be able to do more is photograph more exoplanets directly; not just the big ones, but especially ones that are similar to Earth in size, in the habitable zones of their stars. As Benjamin Mazin, whose lab is leading UC Santa Barbara’s part of the effort, said in a statement:

As a result of this observational bias, there are very few examples of detected Earth-like planets.

Artist’s conception of Kepler-186f, the first Earth-sized exoplanet discovered orbiting in the habitable zone of its star. The new technology being developed could enable scientists to finally directly image some of these worlds and determine whether they are actually habitable or not. Image via NASA Ames/ JPL-Caltech/ T. Pyle/ Phys.org.

How exciting would it be to finally see worlds that may be similar to Earth in some ways?

But seeing them is only part of what makes this so important. By doing so, researchers could more easily analyze the light from these worlds and search for possible biosignatures in their atmospheres, gases that could be produced by life, such as oxygen or methane. Mazin said:

Measuring the atmospheric composition of rocky exoplanets for biosignatures calls for a new observational method.

Beta Pictoris b is one of the few exoplanets that scientists have been able to photograph so far. This series of images from ESO’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) shows it orbiting its star. Beta Pictoris b is still a young, hot planet, making it easier to directly image. Image via ESO/ Lagrange/ SPHERE consortium.

Scientists could measure the chemical composition of the planet’s atmosphere by using spectroscopy. In this way, the light passing through the planet’s atmosphere can be broken down into its individual colors. Different colors indicate what kinds of chemicals are present in the atmosphere. This has already been done to some extent before, but only for large gas giant type exoplanets. Having actual images of exoplanets would make it easier to study them. Mazin said:

Taking a picture of a nearby solar system is one of the most technologically challenging things we do in astronomy, mainly because Earth’s atmosphere royally messes up the picture. It’s like trying to take a picture through a windshield that’s getting blasted with rain.

While this technology can be used for a variety of different exoplanets, the primary goal is to be able to characterize Earth-sized planets with temperate conditions that could be habitable. We already know of a growing number of such worlds in the habitable zones of their stars, but other factors can affect a planet’s potential habitability, like the composition of its atmosphere, how much radiation it receives from its star, amount of water, etc.

Mazin’s lab is just one of multiple teams of university astronomers that the Heising-Simons Foundation is investing in. This will advance the technology needed to image these kinds of worlds and learn more about their potential habitability.

Benjamin Mazin at UC Santa Barbara, whose lab is helping develop new technology to directly image exoplanets. Image via UC Santa Barbara.

Another key piece of technology being developed by UC Santa Barbara is a new kind of superconducting photon detector called a microwave kinetic inductance detector (MKID), which has been integrated with the 8-meter (26-foot) Subaru Telescope in Hawaii. This also uses Heising-Simons Foundation funding to develop the necessary data processing algorithms. Mazin said:

I feel there is no more compelling problem to work on. Learning about nearby planets tells us a lot about ourselves and our place in the universe.

Only a handful of exoplanets have been directly imaged to date, such as the young, hot giant planet Beta Pictoris b, 63 light-years away. But with this new technology, scientists should now be able to photograph many more distant worlds. While they still won’t look like much more than just bright dots given their extreme distances from us, just being able to see them at all, and better analyze their atmospheres, will be a huge accomplishment. Then, we will be a big step closer to finding potentially habitable worlds that may be similar to ours, and, perhaps, discovering the first evidence of life in an alien solar system.

Bottom line: Researchers at UC Santa Barbara are helping to develop new technology to directly image potentially habitable exoplanets.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2UmpHhL

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire