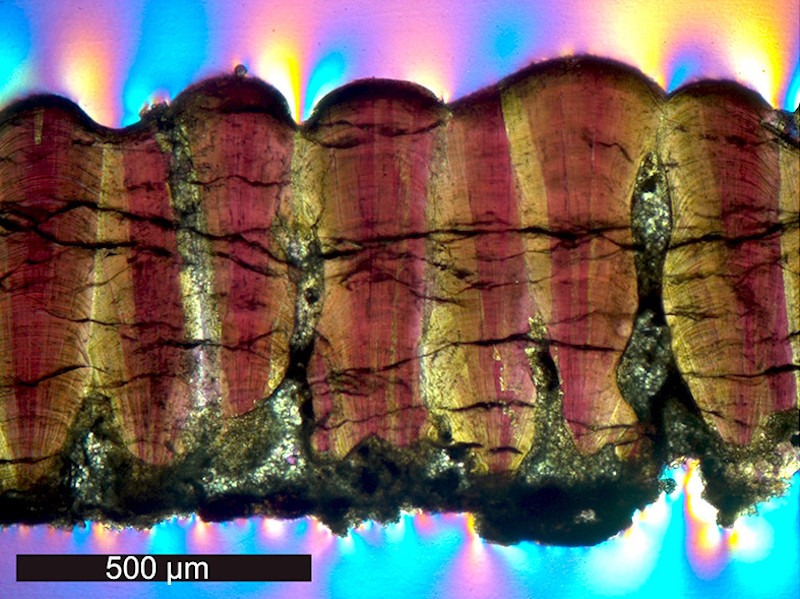

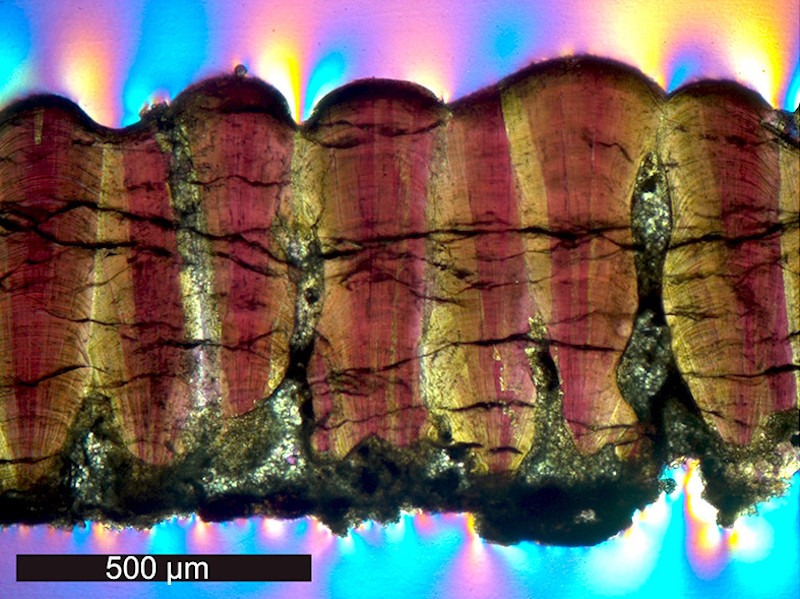

A dinosaur eggshell fossil in cross-section under a microscope using cross-polarizing light. Notice the clusters of biomineralized calcite crystals radiating out from central nodes, along the interior margin of the shell at the bottom of the image. This, and the bumpy surface of the exterior margin (top of image) is usually indicative of titanosaur, sauropod dinosaurs. Image via Robin Dawson/ Yale University.

Warm-blooded animals (such as mammals and birds) produce their own heat and maintain a constant internal body temperature. Cold-blooded animals (such as reptiles and fish) don’t have internal mechanisms for regulating their body temperature; their body temperature depends on their environment. Where do dinosaurs fit in? Cold-blooded? Warm-blooded? Neither? Those are long-standing questions among scientists, but, so far, no evidence has unquestionably proven what dinosaur metabolisms were like. In February 2020, though, a new research study – an analysis of the chemistry of dinosaur eggshells – provides answers that fall into the warm-blooded camp.

Robin Dawson of University of Massachusetts-Amherst is lead author of the new study, which was published February 14, 2020 in the journal Science Advances. She said in a statement:

Dinosaurs sit at an evolutionary point between birds, which are warm-blooded, and reptiles, which are cold-blooded. Our results suggest that all major groups of dinosaurs had warmer body temperatures than their environment.

The researchers tested eggshell fossils representing three major dinosaur groups, including ones more closely related to birds and more distantly related to birds.

The testing process is called clumped isotope paleothermometry. It’s based on the fact that the ordering of oxygen and carbon atoms in a fossil eggshell are determined by temperature. Once you know the ordering of those atoms, the researchers said, you can calculate the mother dinosaur’s internal body temperature.

The Maiasaura were large duck-billed dinosaurs that lived in North America in the Cretaceous Era. An adult maiasaurus is shown here with several hatchlings. Image via Yale University.

The researchers tested fossilized eggshells from Troodons, a small, meat-eating theropod, and the large, duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura in Alberta, Canada, and from Megaloolithus (a species classification limited to dinosaur eggs) from Romania.

The researchers conducted the same analysis on current cold-blooded invertebrate shells in the same locations as the dinosaur eggshells. This helped the researchers determine the temperature of the local environment — and whether dinosaur body temperatures were higher or lower.

Dawson said the Troodon samples were as much as 18 degrees F (10 degrees C) warmer than their environment, the Maiasaura samples were 27 degrees F (15 degrees C) warmer, and the Megaloolithus samples were 5.4-10.8 degrees F (3-6 degrees C) warmer. Dawson said:

What we found indicates that the ability to metabolically raise their temperatures above the environment was an early, evolved trait for dinosaurs.

The researchers also said their findings might add to the ongoing discussion about the role of feathers in early bird evolution. Dawson commented:

It’s possible that dense feathers were primarily selected for insulation, as body size decreased in theropod dinosaurs on the evolutionary pathway to modern birds.

Feathers could have then later been co-opted for sexual display or flying.

Bottom line: A new study that analyzed the chemistry of dinosaur eggshells, suggests that dinosaurs were warm-blooded.

Source: Eggshell geochemistry reveals ancestral metabolic thermoregulation in Dinosauria

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3cuanqm

A dinosaur eggshell fossil in cross-section under a microscope using cross-polarizing light. Notice the clusters of biomineralized calcite crystals radiating out from central nodes, along the interior margin of the shell at the bottom of the image. This, and the bumpy surface of the exterior margin (top of image) is usually indicative of titanosaur, sauropod dinosaurs. Image via Robin Dawson/ Yale University.

Warm-blooded animals (such as mammals and birds) produce their own heat and maintain a constant internal body temperature. Cold-blooded animals (such as reptiles and fish) don’t have internal mechanisms for regulating their body temperature; their body temperature depends on their environment. Where do dinosaurs fit in? Cold-blooded? Warm-blooded? Neither? Those are long-standing questions among scientists, but, so far, no evidence has unquestionably proven what dinosaur metabolisms were like. In February 2020, though, a new research study – an analysis of the chemistry of dinosaur eggshells – provides answers that fall into the warm-blooded camp.

Robin Dawson of University of Massachusetts-Amherst is lead author of the new study, which was published February 14, 2020 in the journal Science Advances. She said in a statement:

Dinosaurs sit at an evolutionary point between birds, which are warm-blooded, and reptiles, which are cold-blooded. Our results suggest that all major groups of dinosaurs had warmer body temperatures than their environment.

The researchers tested eggshell fossils representing three major dinosaur groups, including ones more closely related to birds and more distantly related to birds.

The testing process is called clumped isotope paleothermometry. It’s based on the fact that the ordering of oxygen and carbon atoms in a fossil eggshell are determined by temperature. Once you know the ordering of those atoms, the researchers said, you can calculate the mother dinosaur’s internal body temperature.

The Maiasaura were large duck-billed dinosaurs that lived in North America in the Cretaceous Era. An adult maiasaurus is shown here with several hatchlings. Image via Yale University.

The researchers tested fossilized eggshells from Troodons, a small, meat-eating theropod, and the large, duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura in Alberta, Canada, and from Megaloolithus (a species classification limited to dinosaur eggs) from Romania.

The researchers conducted the same analysis on current cold-blooded invertebrate shells in the same locations as the dinosaur eggshells. This helped the researchers determine the temperature of the local environment — and whether dinosaur body temperatures were higher or lower.

Dawson said the Troodon samples were as much as 18 degrees F (10 degrees C) warmer than their environment, the Maiasaura samples were 27 degrees F (15 degrees C) warmer, and the Megaloolithus samples were 5.4-10.8 degrees F (3-6 degrees C) warmer. Dawson said:

What we found indicates that the ability to metabolically raise their temperatures above the environment was an early, evolved trait for dinosaurs.

The researchers also said their findings might add to the ongoing discussion about the role of feathers in early bird evolution. Dawson commented:

It’s possible that dense feathers were primarily selected for insulation, as body size decreased in theropod dinosaurs on the evolutionary pathway to modern birds.

Feathers could have then later been co-opted for sexual display or flying.

Bottom line: A new study that analyzed the chemistry of dinosaur eggshells, suggests that dinosaurs were warm-blooded.

Source: Eggshell geochemistry reveals ancestral metabolic thermoregulation in Dinosauria

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/3cuanqm

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire