The Big Dipper over a pool in the Utah desert, caught from a canyon littered with the rock art and ruins of Ancestral Puebloans. Photo by Marc Toso.

View larger. | Big and Little Dippers at different seasons, and different times of night, as captured by Matthew Chin in Hong Kong.

A fixture of the northern sky, the Big and Little Dippers swing around the north star Polaris like riders on a Ferris wheel. They go full circle around Polaris once a day – or once every 23 hours and 56 minutes. If you live at temperate latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, simply look northward and chances are that you’ll see the Big Dipper in your nighttime sky. It looks just like its namesake.

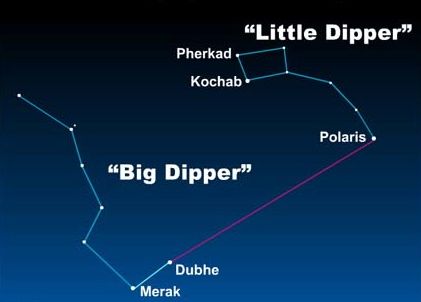

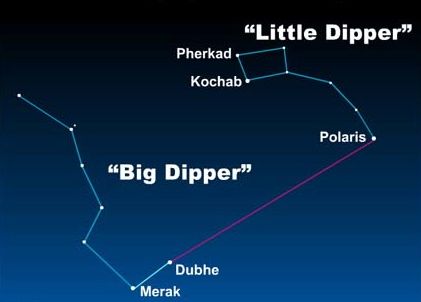

Once you’ve found the Big Dipper, it’s only a hop, skip and jump to Polaris and the Little Dipper.

View larger. | The Big Dipper captured in April 2017 by Kurt Zeppetello. If you look closely at the second star of the handle, Mizar, you can see a smaller companion star, Alcor.

The Big Dipper seen in the midst of the northern lights, taken in by Birgit Boden in northern Sweden.

Depending upon the season of the year, the Big Dipper can be found high in the northern sky or low in the northern sky. Just remember the old saying spring up and fall down. On spring and summer evenings, the Big Dipper shines highest in the sky. On autumn and winter evenings, the Big Dipper lurks closest to the horizon.

Given an unobstructed horizon, latitudes at and north of Little Rock, Arkansas (35 degrees north), can expect to see the Big Dipper at any hour of the night for all days of the year. As for the Little Dipper, it is circumpolar – always above the horizon – as far south as the Tropic of Cancer (23.5 degrees north latitude).

Stars in the Big Dipper via EarthSky Facebook friend Ken Christison. He captured this photo in September 2013.

No matter what time of year you look, the two outer stars in the Big Dipper’s bowl always point to Polaris.

Notice that the Big Dipper has two parts – a bowl and a handle. Notice the two outer stars in the bowl of the Big Dipper. They are called Dubhe and Merak, and an imaginary line drawn between them goes to Polaris, the North Star. That’s why Dubhe and Merak are known in skylore as The Pointers.

In turn, Polaris marks the end of the Little Dipper’s Handle. So why isn’t the Little Dipper as easy to pick out as the Big Dipper? The answer is that, like the Big Dipper, the Little Dipper has seven stars. But the four stars between Polaris and the outer bowl stars – Kochab and Pherkad – are rather dim. You need a dark country sky to see all seven.

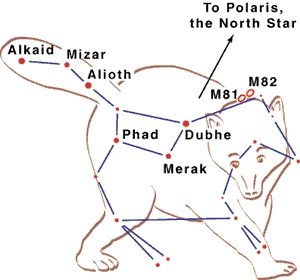

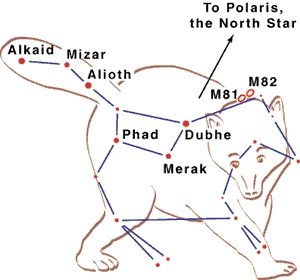

The Big Dipper is part of Ursa Major, the celestial Great Bear. Image via Night Sky Interlude.

The Big Dipper is really an asterism – a star pattern that is not a constellation. The Big Dipper is a clipped version of the constellation Ursa Major the Big Bear, the Big Dipper stars outlining the Bear’s tail and hindquarters. In the star lore of the Mi’kmaw nation in northern Canada, the Big Dipper is also associated with a bear but with a different twist. The Mi’kmaw see the Big Dipper bowl as Celestial Bear, and the three stars of the handle as hunters chasing the Bear.

The starry sky serves as a calendar and a story book, as is beautifully illustrated by the Mi’kmaw tale of Celestial Bear. In autumn, the hunters finally catch up with the Bear, and it’s said that the blood from the Bear colors the autumn landscape. In another version of the story, Celestial Bear hits its nose when coming down to Earth, with its bloody nose giving color to autumn leaves. When Celestial Bear is seen right on the northern horizon on late fall and early winter evenings, it’s a sure sign that the hibernation season is upon us.

The Little Dipper is also an asterism, these stars belonging to the constellation Ursa Minor the Little Bear. In ancient times, the Little Dipper formed the wings of the constellation Draco the Dragon. But when the seafaring Phoenicians met with the Greek astronomer Thales around 600 B.C., they showed him how to use the Little Dipper stars to navigate. Thereby, Thales clipped Draco’s wings, to create a new constellation that gave Greek sailors a new way to steer by the stars.

In Thales’s day, the stars Kochab and Pherkad (rather than Polaris) marked the approximate direction of the north celestial pole – the point in the sky that is directly above the Earth’s North Pole.

To this day, Kochab and Pherkad are still known as the Guardians of the Pole.

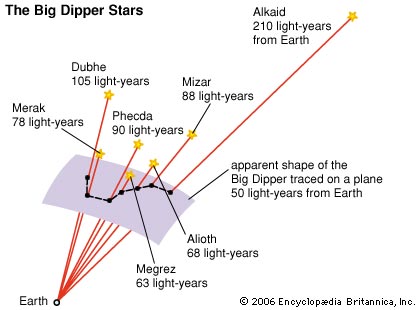

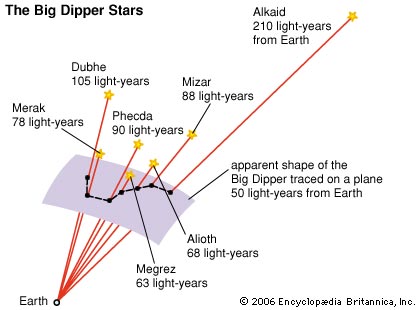

Astronomers have found that the stars of the Big Dipper (excepting the pointer star, Dubhe, and the handle star, Alkaid) belong to an association of stars known as the Ursa Major Moving Cluster. Here are the stars of the Big Dipper, at their various distances from Earth, via AstroPixie.

Astronomers sometimes speak of the fixed stars, but they know that the stars are not truly fixed. They move in space. Thus the star patterns that we see today will slowly but surely drift apart over the long course of time.

But even 25,000 years from now, the Big Dipper pattern will look nearly the same as its does today. Astronomers have found that the stars of the Big Dipper (excepting the pointer star, Dubhe, and the handle star, Alkaid) belong to an association of stars known as the Ursa Major Moving Cluster. These stars, loosely bound by gravity, drift in the same direction in space.

In 100,000 years, this pattern of Big Dipper stars (minus Dubhe and Alkaid) will appear much as it does today! But there will be some differences, as illustrated in the drawing below:

Stars of the Big Dipper today – 100,000 years ago – and 100,000 years from now via AstroPixie.

The Big Dipper as seen by John Michael Mizzi on the island of Gozo, south of Italy.

Bottom line: All about the Big and Little Dippers. How to spot them, their mythology, plus learn how the stars of the Big Dipper are moving in space.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2UcDIP0

The Big Dipper over a pool in the Utah desert, caught from a canyon littered with the rock art and ruins of Ancestral Puebloans. Photo by Marc Toso.

View larger. | Big and Little Dippers at different seasons, and different times of night, as captured by Matthew Chin in Hong Kong.

A fixture of the northern sky, the Big and Little Dippers swing around the north star Polaris like riders on a Ferris wheel. They go full circle around Polaris once a day – or once every 23 hours and 56 minutes. If you live at temperate latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere, simply look northward and chances are that you’ll see the Big Dipper in your nighttime sky. It looks just like its namesake.

Once you’ve found the Big Dipper, it’s only a hop, skip and jump to Polaris and the Little Dipper.

View larger. | The Big Dipper captured in April 2017 by Kurt Zeppetello. If you look closely at the second star of the handle, Mizar, you can see a smaller companion star, Alcor.

The Big Dipper seen in the midst of the northern lights, taken in by Birgit Boden in northern Sweden.

Depending upon the season of the year, the Big Dipper can be found high in the northern sky or low in the northern sky. Just remember the old saying spring up and fall down. On spring and summer evenings, the Big Dipper shines highest in the sky. On autumn and winter evenings, the Big Dipper lurks closest to the horizon.

Given an unobstructed horizon, latitudes at and north of Little Rock, Arkansas (35 degrees north), can expect to see the Big Dipper at any hour of the night for all days of the year. As for the Little Dipper, it is circumpolar – always above the horizon – as far south as the Tropic of Cancer (23.5 degrees north latitude).

Stars in the Big Dipper via EarthSky Facebook friend Ken Christison. He captured this photo in September 2013.

No matter what time of year you look, the two outer stars in the Big Dipper’s bowl always point to Polaris.

Notice that the Big Dipper has two parts – a bowl and a handle. Notice the two outer stars in the bowl of the Big Dipper. They are called Dubhe and Merak, and an imaginary line drawn between them goes to Polaris, the North Star. That’s why Dubhe and Merak are known in skylore as The Pointers.

In turn, Polaris marks the end of the Little Dipper’s Handle. So why isn’t the Little Dipper as easy to pick out as the Big Dipper? The answer is that, like the Big Dipper, the Little Dipper has seven stars. But the four stars between Polaris and the outer bowl stars – Kochab and Pherkad – are rather dim. You need a dark country sky to see all seven.

The Big Dipper is part of Ursa Major, the celestial Great Bear. Image via Night Sky Interlude.

The Big Dipper is really an asterism – a star pattern that is not a constellation. The Big Dipper is a clipped version of the constellation Ursa Major the Big Bear, the Big Dipper stars outlining the Bear’s tail and hindquarters. In the star lore of the Mi’kmaw nation in northern Canada, the Big Dipper is also associated with a bear but with a different twist. The Mi’kmaw see the Big Dipper bowl as Celestial Bear, and the three stars of the handle as hunters chasing the Bear.

The starry sky serves as a calendar and a story book, as is beautifully illustrated by the Mi’kmaw tale of Celestial Bear. In autumn, the hunters finally catch up with the Bear, and it’s said that the blood from the Bear colors the autumn landscape. In another version of the story, Celestial Bear hits its nose when coming down to Earth, with its bloody nose giving color to autumn leaves. When Celestial Bear is seen right on the northern horizon on late fall and early winter evenings, it’s a sure sign that the hibernation season is upon us.

The Little Dipper is also an asterism, these stars belonging to the constellation Ursa Minor the Little Bear. In ancient times, the Little Dipper formed the wings of the constellation Draco the Dragon. But when the seafaring Phoenicians met with the Greek astronomer Thales around 600 B.C., they showed him how to use the Little Dipper stars to navigate. Thereby, Thales clipped Draco’s wings, to create a new constellation that gave Greek sailors a new way to steer by the stars.

In Thales’s day, the stars Kochab and Pherkad (rather than Polaris) marked the approximate direction of the north celestial pole – the point in the sky that is directly above the Earth’s North Pole.

To this day, Kochab and Pherkad are still known as the Guardians of the Pole.

Astronomers have found that the stars of the Big Dipper (excepting the pointer star, Dubhe, and the handle star, Alkaid) belong to an association of stars known as the Ursa Major Moving Cluster. Here are the stars of the Big Dipper, at their various distances from Earth, via AstroPixie.

Astronomers sometimes speak of the fixed stars, but they know that the stars are not truly fixed. They move in space. Thus the star patterns that we see today will slowly but surely drift apart over the long course of time.

But even 25,000 years from now, the Big Dipper pattern will look nearly the same as its does today. Astronomers have found that the stars of the Big Dipper (excepting the pointer star, Dubhe, and the handle star, Alkaid) belong to an association of stars known as the Ursa Major Moving Cluster. These stars, loosely bound by gravity, drift in the same direction in space.

In 100,000 years, this pattern of Big Dipper stars (minus Dubhe and Alkaid) will appear much as it does today! But there will be some differences, as illustrated in the drawing below:

Stars of the Big Dipper today – 100,000 years ago – and 100,000 years from now via AstroPixie.

The Big Dipper as seen by John Michael Mizzi on the island of Gozo, south of Italy.

Bottom line: All about the Big and Little Dippers. How to spot them, their mythology, plus learn how the stars of the Big Dipper are moving in space.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2UcDIP0

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire