Artist’s concept of a gas giant exoplanet orbiting close to its star. The new study suggests water vapor is common on such worlds, but maybe in lesser amounts than thought. Image via Amanda Smith/ University of Cambridge.

Water – needed for life as we know it – has turned out to be common in our solar system. Besides Earth, of course, there are moons in the outer solar system with oceans beneath their icy surfaces. Ice can be found almost everywhere in our neighborhood of space, even on the moon and Mercury! But what about in other solar systems? A new study, led by researchers from the University of Cambridge, suggests that water may be at the same time both plentiful and scarce, depending on the type of planets involved.

The new findings were announced by Cambridge on December 11, 2019, and the peer-reviewed paper was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on the same day.

The researchers studied atmospheric data from 19 known exoplanets to learn more about their chemical and thermal properties. These planets ranged from mini-Neptunes (nearly 10 Earth masses) to super-Jupiters (over 600 Earth masses). Temperatures on these worlds range from 20 degrees Celsius (about 70 degrees Fahrenheit) to over 2,000 degrees Celsius (3,600 F). These planets are similar to the gas and ice giants in our solar system, but they orbit a variety of different types of stars. Study leader Nikku Madhusudhan, of the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge, said:

We are seeing the first signs of chemical patterns in extra-terrestrial worlds, and we’re seeing just how diverse they can be in terms of their chemical compositions.

EarthSky 2020 lunar calendars are available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

Artist’s concept of a mini-Neptune exoplanet. Water vapor was recently detected in the atmosphere of a world such as this. Image via ESA/ Hubble/ M. Kornmesser/ Bad Astronomy.

The findings are challenging current theories on planetary formation.

Both ground and space-based telescopes were used to gather spectrographic data from the planets, including the Hubble Space Telescope, the Spitzer Space Telescope, the Very Large Telescope in Chile and the Gran Telescopio Canarias in Spain. The researchers were able to estimate the chemical abundances of the atmospheres of all the planets.

Based on what we know about the giant planets in our own solar system, these kinds of exoplanets were predicted to have similar high abundances of certain elements such as hydrogen, oxygen and water. So what did they find?

The results showed that 14 of the planets had an abundance of water vapor, as well as an abundance of sodium and potassium in six planets each. This suggests that there is a depletion of oxygen relative to the other elements and that the planets may have evolved with little accretion of ice. As Madhusudhan noted:

It is incredible to see such low water abundances in the atmospheres of a broad range of planets orbiting a variety of stars.

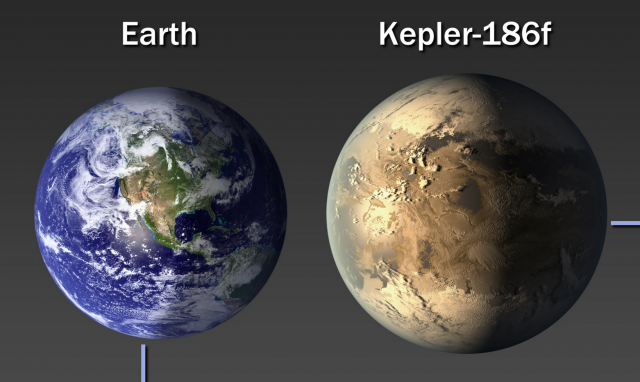

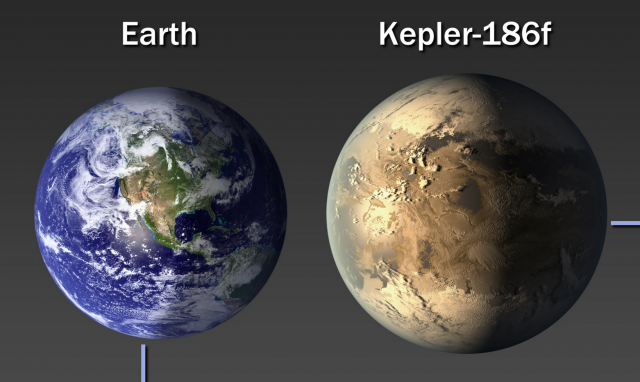

Comparison of exoplanet Kepler-186f with Earth (artist’s concept). Some of these Earth-sized rocky worlds should also be able to have liquid water on their surfaces, although that research was not part of this particular study, which focused on giant gas and ice planets. Image via NASA Ames/ SETI Institute/ JPL-Caltech/ Ars Technica.

This means that exoplanets can be more diverse than previously thought in terms of atmospheric composition and water content, which challenges several theoretical models of planet formation. Different chemical elements can no longer just be assumed to be equally abundant in planetary atmospheres.

It’s not easy measuring how much water there is in the atmospheres of planets so far away, but it can even be challenging for planets much closer to home. Jupiter is a prime example of this. According to Luis Welbanks, lead author of the study:

Measuring the abundances of these chemicals in exoplanetary atmospheres is something extraordinary, considering that we have not been able to do the same for giant planets in our solar system yet, including Jupiter, our nearest gas giant neighbor.

Since Jupiter is so cold, any water vapor in its atmosphere would be condensed, making it difficult to measure. If the water abundance in Jupiter were found to be plentiful as predicted, it would imply that it formed in a different way to the exoplanets we looked at in the current study.

Determining the amount of water vapor in the atmospheres of the giant planets even in our own solar system can be challenging. This is Jupiter as seen by the Juno spacecraft on April 1, 2018. Image via NASA/ JPL-Caltech/ SwRI/ MSSS/ Gerald Eichstad/ Sean Doran/ Newsweek.

As already mentioned, the sample size of planets in the study is quite small, so researchers want to expand on it in the future. Madhusudhan commented:

We look forward to increasing the size of our planet sample in future studies. Inevitably, we expect to find outliers to the current trends as well as measurements of other chemicals.

It should also be noted that this current study did not include smaller rocky super-Earth or Earth-sized planets, which are now known to be quite common in our galaxy. Those are the kinds of worlds where the amount of water would have the most consequence in terms of the potential habitability of a planet.

As Madhusudhan said:

Given that water is a key ingredient to our notion of habitability on Earth, it is important to know how much water can be found in planetary systems beyond our own.

Luis Welbanks, lead author of the new study. Image via University of Cambridge.

While this study may be limited regarding the types of exoplanets known to exist, it provides an important insight into how much water could be expected to be discovered among a large population of such worlds. This will help scientists better understand how these planets formed, and perhaps provide clues as to how many potentially habitable planets there may be as well, when combined with additional future studies of rocky worlds more similar to Earth.

Bottom line: A new study from the University of Cambridge shows that water vapor is common in the atmospheres of at least some larger exoplanets, but in lesser amounts than expected.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2EpVHsn

Artist’s concept of a gas giant exoplanet orbiting close to its star. The new study suggests water vapor is common on such worlds, but maybe in lesser amounts than thought. Image via Amanda Smith/ University of Cambridge.

Water – needed for life as we know it – has turned out to be common in our solar system. Besides Earth, of course, there are moons in the outer solar system with oceans beneath their icy surfaces. Ice can be found almost everywhere in our neighborhood of space, even on the moon and Mercury! But what about in other solar systems? A new study, led by researchers from the University of Cambridge, suggests that water may be at the same time both plentiful and scarce, depending on the type of planets involved.

The new findings were announced by Cambridge on December 11, 2019, and the peer-reviewed paper was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on the same day.

The researchers studied atmospheric data from 19 known exoplanets to learn more about their chemical and thermal properties. These planets ranged from mini-Neptunes (nearly 10 Earth masses) to super-Jupiters (over 600 Earth masses). Temperatures on these worlds range from 20 degrees Celsius (about 70 degrees Fahrenheit) to over 2,000 degrees Celsius (3,600 F). These planets are similar to the gas and ice giants in our solar system, but they orbit a variety of different types of stars. Study leader Nikku Madhusudhan, of the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge, said:

We are seeing the first signs of chemical patterns in extra-terrestrial worlds, and we’re seeing just how diverse they can be in terms of their chemical compositions.

EarthSky 2020 lunar calendars are available! They make great gifts. Order now. Going fast!

Artist’s concept of a mini-Neptune exoplanet. Water vapor was recently detected in the atmosphere of a world such as this. Image via ESA/ Hubble/ M. Kornmesser/ Bad Astronomy.

The findings are challenging current theories on planetary formation.

Both ground and space-based telescopes were used to gather spectrographic data from the planets, including the Hubble Space Telescope, the Spitzer Space Telescope, the Very Large Telescope in Chile and the Gran Telescopio Canarias in Spain. The researchers were able to estimate the chemical abundances of the atmospheres of all the planets.

Based on what we know about the giant planets in our own solar system, these kinds of exoplanets were predicted to have similar high abundances of certain elements such as hydrogen, oxygen and water. So what did they find?

The results showed that 14 of the planets had an abundance of water vapor, as well as an abundance of sodium and potassium in six planets each. This suggests that there is a depletion of oxygen relative to the other elements and that the planets may have evolved with little accretion of ice. As Madhusudhan noted:

It is incredible to see such low water abundances in the atmospheres of a broad range of planets orbiting a variety of stars.

Comparison of exoplanet Kepler-186f with Earth (artist’s concept). Some of these Earth-sized rocky worlds should also be able to have liquid water on their surfaces, although that research was not part of this particular study, which focused on giant gas and ice planets. Image via NASA Ames/ SETI Institute/ JPL-Caltech/ Ars Technica.

This means that exoplanets can be more diverse than previously thought in terms of atmospheric composition and water content, which challenges several theoretical models of planet formation. Different chemical elements can no longer just be assumed to be equally abundant in planetary atmospheres.

It’s not easy measuring how much water there is in the atmospheres of planets so far away, but it can even be challenging for planets much closer to home. Jupiter is a prime example of this. According to Luis Welbanks, lead author of the study:

Measuring the abundances of these chemicals in exoplanetary atmospheres is something extraordinary, considering that we have not been able to do the same for giant planets in our solar system yet, including Jupiter, our nearest gas giant neighbor.

Since Jupiter is so cold, any water vapor in its atmosphere would be condensed, making it difficult to measure. If the water abundance in Jupiter were found to be plentiful as predicted, it would imply that it formed in a different way to the exoplanets we looked at in the current study.

Determining the amount of water vapor in the atmospheres of the giant planets even in our own solar system can be challenging. This is Jupiter as seen by the Juno spacecraft on April 1, 2018. Image via NASA/ JPL-Caltech/ SwRI/ MSSS/ Gerald Eichstad/ Sean Doran/ Newsweek.

As already mentioned, the sample size of planets in the study is quite small, so researchers want to expand on it in the future. Madhusudhan commented:

We look forward to increasing the size of our planet sample in future studies. Inevitably, we expect to find outliers to the current trends as well as measurements of other chemicals.

It should also be noted that this current study did not include smaller rocky super-Earth or Earth-sized planets, which are now known to be quite common in our galaxy. Those are the kinds of worlds where the amount of water would have the most consequence in terms of the potential habitability of a planet.

As Madhusudhan said:

Given that water is a key ingredient to our notion of habitability on Earth, it is important to know how much water can be found in planetary systems beyond our own.

Luis Welbanks, lead author of the new study. Image via University of Cambridge.

While this study may be limited regarding the types of exoplanets known to exist, it provides an important insight into how much water could be expected to be discovered among a large population of such worlds. This will help scientists better understand how these planets formed, and perhaps provide clues as to how many potentially habitable planets there may be as well, when combined with additional future studies of rocky worlds more similar to Earth.

Bottom line: A new study from the University of Cambridge shows that water vapor is common in the atmospheres of at least some larger exoplanets, but in lesser amounts than expected.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2EpVHsn

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire