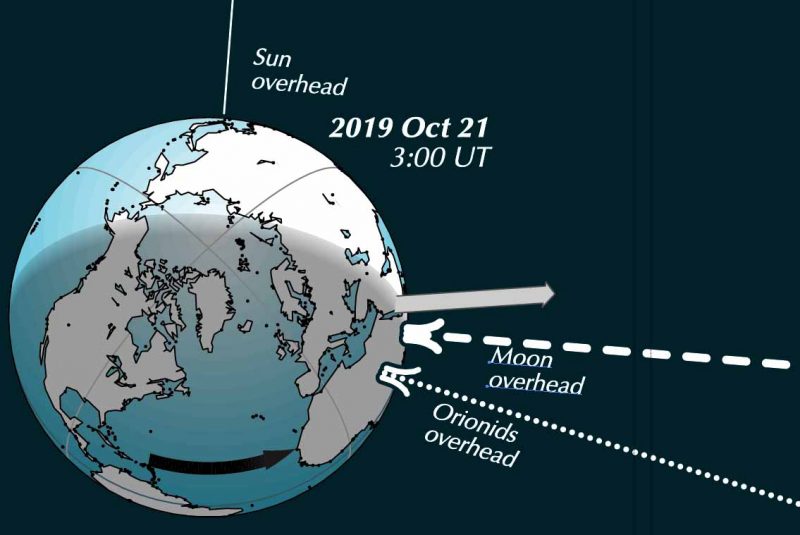

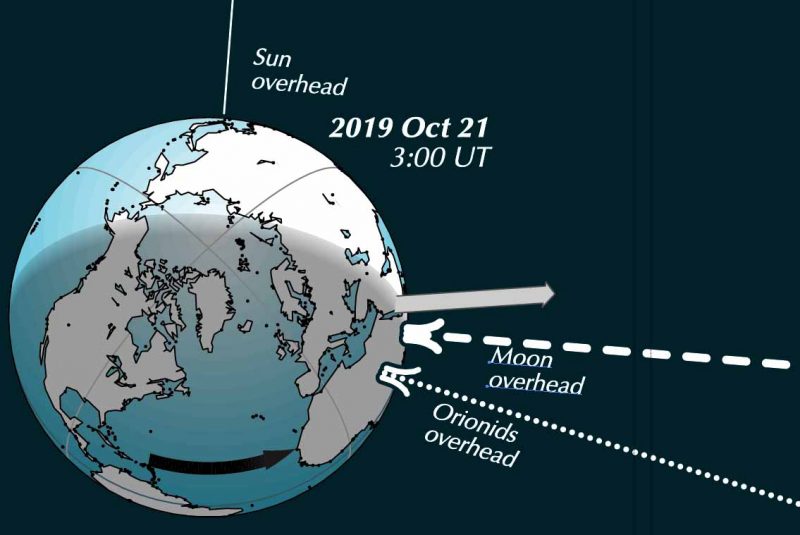

View larger. | Here is the scene Sunday and Monday evenings – from Northern Hemisphere locations – as the Orionid meteors’ radiant rises into view. Notice the moon will be ascending in the sky at the same time. From the Southern Hemisphere, where this shower is also visible, the view is much the same, but the ecliptic – or path of the sun, moon and planets – and the celestial equator would be oriented differently with respect to the horizon. Chart via Guy Ottewell’s blog.

Originally printed at Guy Ottewell’s blog. Re-printed here with permission.

You may already have seen outlying meteors of the annual Orionid shower. They should reach a peak on the mornings of October 21 and 22, in the hours after midnight. Their zenithal hourly rate – the number one alert person might count in an hour at the peak time, in perfect conditions and with the meteors coming from overhead – may be 25. You’ll be very lucky if you manage to count that many, especially as this year there is a last quarter moon in the sky at the same time.

The radiant of a meteor shower is the point or small area among the stars from which the meteors seem to fly. They are particles of dusk or rock shed long ago from a comet – in this case, periodic comet 1P Halley.

The particles emit light as they hit Earth’s atmosphere and burn up. Really, they are on parallel tracks, many miles apart, and can appear in any part of the sky. If you can trace one of these shining trails back to the Orion-Gemini constellations in our sky, it was an Orionid and not a sporadic meteor.

View larger. | Here is the Orionid meteor stream (dotted line) striking Earth Sunday night. Guy Ottewell – who made this chart – lives in England, and he’s showing you Europe’s perspective tonight. The shower’s peak is likely Tuesday morning although Monday morning is good, too. The actual stream of particles in space – the meteor stream, debris left behind by Halley’s Comet – is millions of miles wide. People on all parts of Earth have a more or less equal chance of catching an Orionid meteor streaking across a dark night sky. Chart via Guy Ottewell’s blog.

In the picture above, Earth is seen from ecliptic north (the north pole of its orbit). The broad flat arrow shows its flight along its orbit in one minute, and the arrow on its equator shows its rotation in 3 hours. The actual stream of particles in space is millions of miles wide; the dotted line represents only those that happen to arrive from exactly overhead.

For Europe at this time, just before dawn, the Orionid radiant and the moon are almost overhead. America is moving around toward midnight and toward a nearer view of the hemisphere of sky in which the meteors can appear.

From all parts of Earth … the reason you may see more of these meteors after midnight, especially toward dawn, is that we are going to meet them: they are hitting Earth’s advancing front side, as shown in the illustration above. And that is because the orbit of their famous parent, Comet Halley, is retrograde – counter to the orbits of Earth and the other major planets.

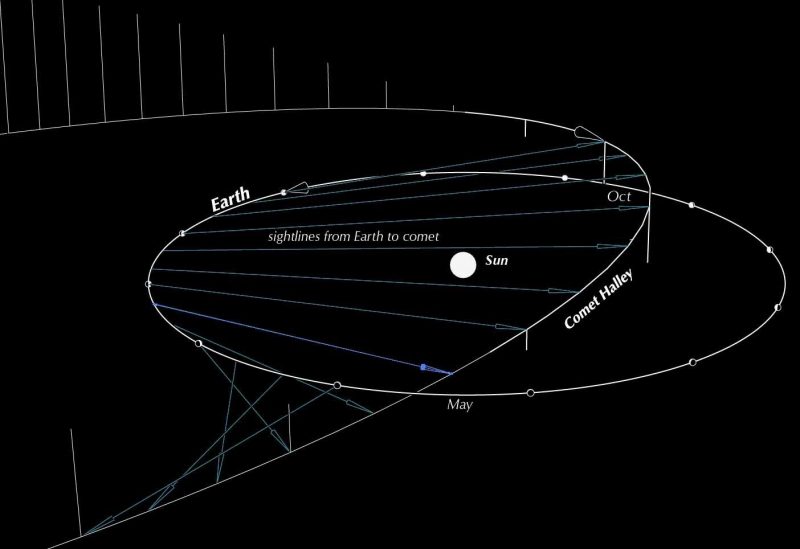

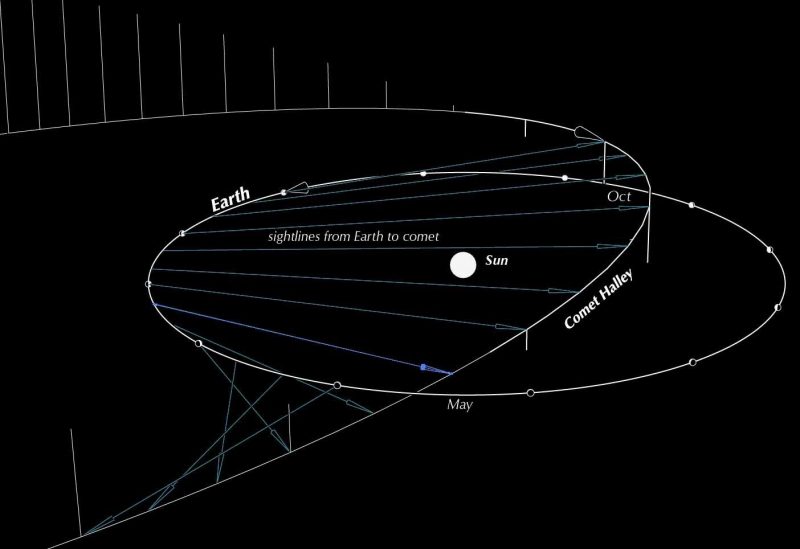

View larger. | This space diagram shows the path of Comet Halley during the most recent of its 76-years-apart visits, in late 1975 and early 1986. The stalks down or up to the ecliptic plane are at intervals of one month. The blue arrows are sightlines from Earth to the comet. Chart via Guy Ottewell’s blog.

You can see that the inward track is across the October part of Earth’s orbit. That’s why we see Orionid meteors in October. And the outward track is across our orbit in May. And so we shall see a second Halley-derived shower, the Eta Aquarids, in May. The orbit does not exactly intersect Earth’s. We see meteors because the particles shed by a comet gradually diverge from its orbit, filling a vast tube of space.

Bottom line: Charts and insights about this week’s Orionid meteor shower from astronomer Guy Ottewell.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Mzw6SV

View larger. | Here is the scene Sunday and Monday evenings – from Northern Hemisphere locations – as the Orionid meteors’ radiant rises into view. Notice the moon will be ascending in the sky at the same time. From the Southern Hemisphere, where this shower is also visible, the view is much the same, but the ecliptic – or path of the sun, moon and planets – and the celestial equator would be oriented differently with respect to the horizon. Chart via Guy Ottewell’s blog.

Originally printed at Guy Ottewell’s blog. Re-printed here with permission.

You may already have seen outlying meteors of the annual Orionid shower. They should reach a peak on the mornings of October 21 and 22, in the hours after midnight. Their zenithal hourly rate – the number one alert person might count in an hour at the peak time, in perfect conditions and with the meteors coming from overhead – may be 25. You’ll be very lucky if you manage to count that many, especially as this year there is a last quarter moon in the sky at the same time.

The radiant of a meteor shower is the point or small area among the stars from which the meteors seem to fly. They are particles of dusk or rock shed long ago from a comet – in this case, periodic comet 1P Halley.

The particles emit light as they hit Earth’s atmosphere and burn up. Really, they are on parallel tracks, many miles apart, and can appear in any part of the sky. If you can trace one of these shining trails back to the Orion-Gemini constellations in our sky, it was an Orionid and not a sporadic meteor.

View larger. | Here is the Orionid meteor stream (dotted line) striking Earth Sunday night. Guy Ottewell – who made this chart – lives in England, and he’s showing you Europe’s perspective tonight. The shower’s peak is likely Tuesday morning although Monday morning is good, too. The actual stream of particles in space – the meteor stream, debris left behind by Halley’s Comet – is millions of miles wide. People on all parts of Earth have a more or less equal chance of catching an Orionid meteor streaking across a dark night sky. Chart via Guy Ottewell’s blog.

In the picture above, Earth is seen from ecliptic north (the north pole of its orbit). The broad flat arrow shows its flight along its orbit in one minute, and the arrow on its equator shows its rotation in 3 hours. The actual stream of particles in space is millions of miles wide; the dotted line represents only those that happen to arrive from exactly overhead.

For Europe at this time, just before dawn, the Orionid radiant and the moon are almost overhead. America is moving around toward midnight and toward a nearer view of the hemisphere of sky in which the meteors can appear.

From all parts of Earth … the reason you may see more of these meteors after midnight, especially toward dawn, is that we are going to meet them: they are hitting Earth’s advancing front side, as shown in the illustration above. And that is because the orbit of their famous parent, Comet Halley, is retrograde – counter to the orbits of Earth and the other major planets.

View larger. | This space diagram shows the path of Comet Halley during the most recent of its 76-years-apart visits, in late 1975 and early 1986. The stalks down or up to the ecliptic plane are at intervals of one month. The blue arrows are sightlines from Earth to the comet. Chart via Guy Ottewell’s blog.

You can see that the inward track is across the October part of Earth’s orbit. That’s why we see Orionid meteors in October. And the outward track is across our orbit in May. And so we shall see a second Halley-derived shower, the Eta Aquarids, in May. The orbit does not exactly intersect Earth’s. We see meteors because the particles shed by a comet gradually diverge from its orbit, filling a vast tube of space.

Bottom line: Charts and insights about this week’s Orionid meteor shower from astronomer Guy Ottewell.

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2Mzw6SV

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire