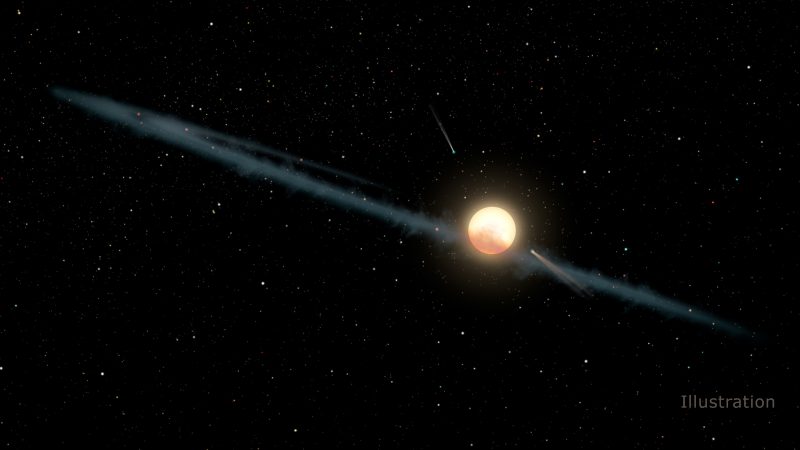

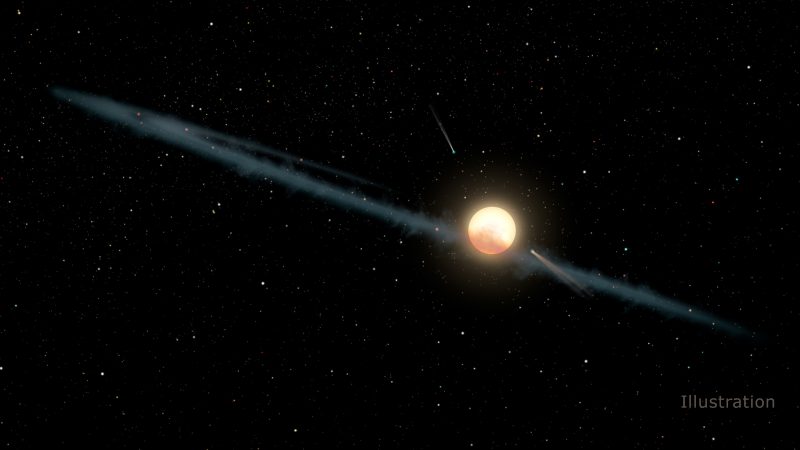

Artist’s concept of a hypothetical uneven ring of dust causing the mysterious dimming of Tabby’s Star, also known as KIC 8462852 or Boyajian’s Star. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/Columbia University.

Tabby’s Star – aka KIC 8462852 or Boyajian’s Star – has been fascinating astronomers and the public alike for the past few years now, with its weird abrupt dimmings in brightness. Theories have ranged from comets to black holes to alien megastructures to explain the odd dips. On September 16, scientists at Columbia University said they have come up with yet another possibility: a melting exomoon.

The new peer-reviewed paper was published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society on September 5, 2019.

The new study focuses on the long-term dimming of Tabby’s Star, where evidence indicates that it has been gradually dimming overall for the past few decades or even centuries, if not longer. Studies have shown that the star dimmed by 14% between 1890 and 1989. This is separate from the other occasional dips, where the brightness of the star will suddenly dim for a few hours or days and then return to normal. Some of those dips have been as little as about 1%, while others as much as a whopping 22%.

But the gradual long-term dimming has been just as puzzling. The new scenario proposed involves a large icy exomoon – a moon orbiting a planet in another solar system – that is slowly “melting” or evaporating. As astrophysicist Brian Metzger of Columbia – a co-author on the new study – explained:

The exomoon is like a comet of ice that is evaporating and spewing off these rocks into space. Eventually the exomoon will completely evaporate, but it will take millions of years for the moon to be melted and consumed by the star. We’re so lucky to see this evaporation event happen.

Theories about Tabby’s Star have ranged from comets to alien megastructures. Could the explanation really be an evaporating exomoon? Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/Sky & Telescope.

An exomoon being slowly destroyed could also explain the other briefer, random dips. The moon could be ripped away from its planet, and in some cases, the moon could end up orbiting the star instead. When that happens, radiation from the star could tear away the outer layers of the moon, creating dust clouds. Those dust clouds could then cause the dips in brightness when they pass between the star and Earth.

But what about the long-term dimming? If an exomoon was torn apart, then pieces of it could still be present in the new orbit around the star where the moon had been pulled into. Larger-grained material forms a disk around the star, while smaller-grained clouds of dust pass through it, and larger particles can be moved closer to the star. All of this affects the opaqueness of the disk over time.

The idea of a planet and moon moving closer to its star and being destroyed is unique among the hypotheses offered for Tabby’s Star.

Tabetha Boyajian, who helped bring mystery star KIC 8462852 to public attention. Image via exoplanets.astro.yale.edu.

Astrophysicist Miguel Martinez of Columbia University led the new research on Tabby’s Star. He said:

It naturally results in the orphaned exomoons ending up on (highly eccentric) orbits with precisely the properties previous research had shown were needed to explain the dimming of Tabby’s star. No other previous model was able to put all these pieces together.

If this hypothesis is correct, then another question is whether such events are rare, or could they be more common? Dips in brightness of some stars is seen quite often, but these tend to be much younger stars that still have disks of dust and gas around them, where planets can form. Tabby’s Star, however, is older and more like our own sun. The Kepler Space Telescope looked at hundreds of thousands of stars, but only saw one acting the way Tabby’s Star doesL Tabby’s Star itself. That’s not to say that Tabby’s Star is the only weird one found so far.

For example, consider the so-called Random Transiter – HD 139139 – a binary star system 350 light-years from Earth. This star, also seen by Kepler, was found over a period of 87 days to undergo up to 28 transits, that is, 28 objects passing in front of the star, looking just like planets, and all the same size, except for one larger one. The problem is that there is no evidence of regular, periodic orbits for these 28 objects, as would be expected for planets. And why are they all mostly the same size? Hence the moniker Random Transiter.

Miguel Martinez of Columbia University led the new research on Tabby’s Star. Image via Miguel Martinez.

If an evaporating exomoon really does explain Tabby’s Star, then that would also be compelling evidence that exomoons are common in our galaxy, as scientists think they should be (although a lot harder to detect). According to Metzger:

We don’t really have any evidence that moons exist outside of our solar system, but a moon being thrown off into its host star can’t be that uncommon. This is a contribution to the broadening of our knowledge of the exotic happenings in other solar systems that we wouldn’t have known 20 or 30 years ago.

The researchers seem to have made a good case for their melting exomoon idea, so it will be interesting to see what continued observations show, and if other scientists can support their findings. But it seems certain that Tabby’s Star will continue to be one of the most fascinating discoveries in space science regardless.

Bottom line: A new hypothesis could explain both the weird short dips and long-term dimming of Tabby’s Star: a “melting exomoon.”

Source: Orphaned Exomoons: Tidal Detachment and Evaporation Following an Exoplanet-Star Collision

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2m8vKYI

Artist’s concept of a hypothetical uneven ring of dust causing the mysterious dimming of Tabby’s Star, also known as KIC 8462852 or Boyajian’s Star. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/Columbia University.

Tabby’s Star – aka KIC 8462852 or Boyajian’s Star – has been fascinating astronomers and the public alike for the past few years now, with its weird abrupt dimmings in brightness. Theories have ranged from comets to black holes to alien megastructures to explain the odd dips. On September 16, scientists at Columbia University said they have come up with yet another possibility: a melting exomoon.

The new peer-reviewed paper was published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society on September 5, 2019.

The new study focuses on the long-term dimming of Tabby’s Star, where evidence indicates that it has been gradually dimming overall for the past few decades or even centuries, if not longer. Studies have shown that the star dimmed by 14% between 1890 and 1989. This is separate from the other occasional dips, where the brightness of the star will suddenly dim for a few hours or days and then return to normal. Some of those dips have been as little as about 1%, while others as much as a whopping 22%.

But the gradual long-term dimming has been just as puzzling. The new scenario proposed involves a large icy exomoon – a moon orbiting a planet in another solar system – that is slowly “melting” or evaporating. As astrophysicist Brian Metzger of Columbia – a co-author on the new study – explained:

The exomoon is like a comet of ice that is evaporating and spewing off these rocks into space. Eventually the exomoon will completely evaporate, but it will take millions of years for the moon to be melted and consumed by the star. We’re so lucky to see this evaporation event happen.

Theories about Tabby’s Star have ranged from comets to alien megastructures. Could the explanation really be an evaporating exomoon? Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/Sky & Telescope.

An exomoon being slowly destroyed could also explain the other briefer, random dips. The moon could be ripped away from its planet, and in some cases, the moon could end up orbiting the star instead. When that happens, radiation from the star could tear away the outer layers of the moon, creating dust clouds. Those dust clouds could then cause the dips in brightness when they pass between the star and Earth.

But what about the long-term dimming? If an exomoon was torn apart, then pieces of it could still be present in the new orbit around the star where the moon had been pulled into. Larger-grained material forms a disk around the star, while smaller-grained clouds of dust pass through it, and larger particles can be moved closer to the star. All of this affects the opaqueness of the disk over time.

The idea of a planet and moon moving closer to its star and being destroyed is unique among the hypotheses offered for Tabby’s Star.

Tabetha Boyajian, who helped bring mystery star KIC 8462852 to public attention. Image via exoplanets.astro.yale.edu.

Astrophysicist Miguel Martinez of Columbia University led the new research on Tabby’s Star. He said:

It naturally results in the orphaned exomoons ending up on (highly eccentric) orbits with precisely the properties previous research had shown were needed to explain the dimming of Tabby’s star. No other previous model was able to put all these pieces together.

If this hypothesis is correct, then another question is whether such events are rare, or could they be more common? Dips in brightness of some stars is seen quite often, but these tend to be much younger stars that still have disks of dust and gas around them, where planets can form. Tabby’s Star, however, is older and more like our own sun. The Kepler Space Telescope looked at hundreds of thousands of stars, but only saw one acting the way Tabby’s Star doesL Tabby’s Star itself. That’s not to say that Tabby’s Star is the only weird one found so far.

For example, consider the so-called Random Transiter – HD 139139 – a binary star system 350 light-years from Earth. This star, also seen by Kepler, was found over a period of 87 days to undergo up to 28 transits, that is, 28 objects passing in front of the star, looking just like planets, and all the same size, except for one larger one. The problem is that there is no evidence of regular, periodic orbits for these 28 objects, as would be expected for planets. And why are they all mostly the same size? Hence the moniker Random Transiter.

Miguel Martinez of Columbia University led the new research on Tabby’s Star. Image via Miguel Martinez.

If an evaporating exomoon really does explain Tabby’s Star, then that would also be compelling evidence that exomoons are common in our galaxy, as scientists think they should be (although a lot harder to detect). According to Metzger:

We don’t really have any evidence that moons exist outside of our solar system, but a moon being thrown off into its host star can’t be that uncommon. This is a contribution to the broadening of our knowledge of the exotic happenings in other solar systems that we wouldn’t have known 20 or 30 years ago.

The researchers seem to have made a good case for their melting exomoon idea, so it will be interesting to see what continued observations show, and if other scientists can support their findings. But it seems certain that Tabby’s Star will continue to be one of the most fascinating discoveries in space science regardless.

Bottom line: A new hypothesis could explain both the weird short dips and long-term dimming of Tabby’s Star: a “melting exomoon.”

Source: Orphaned Exomoons: Tidal Detachment and Evaporation Following an Exoplanet-Star Collision

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2m8vKYI

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire