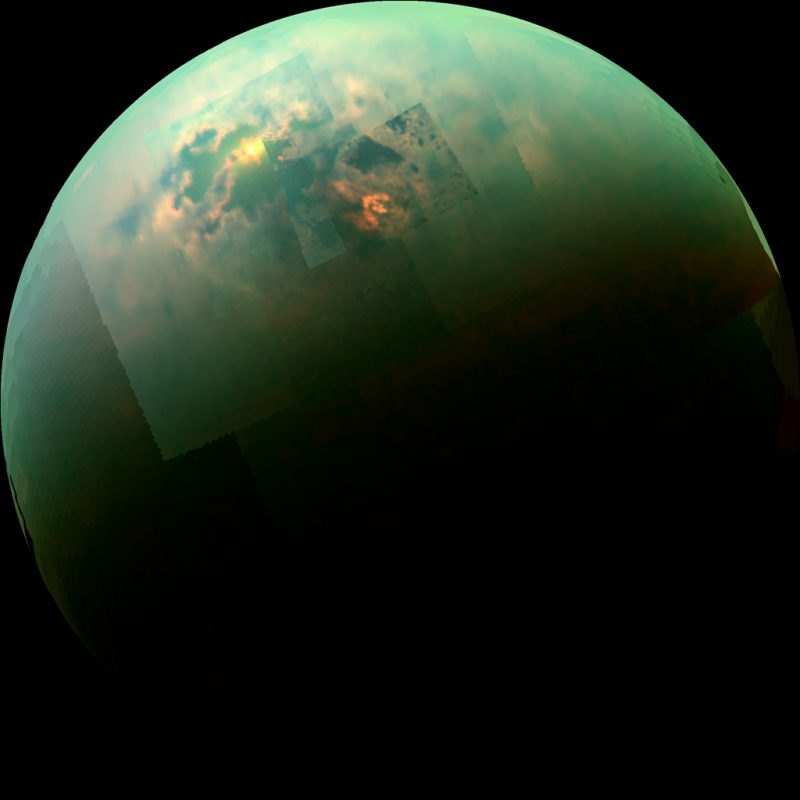

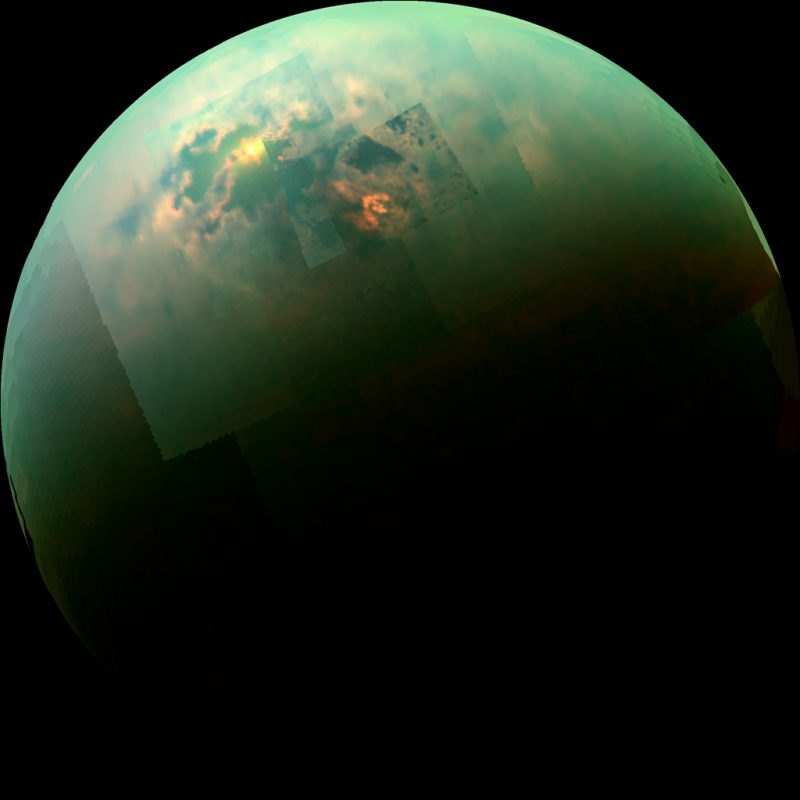

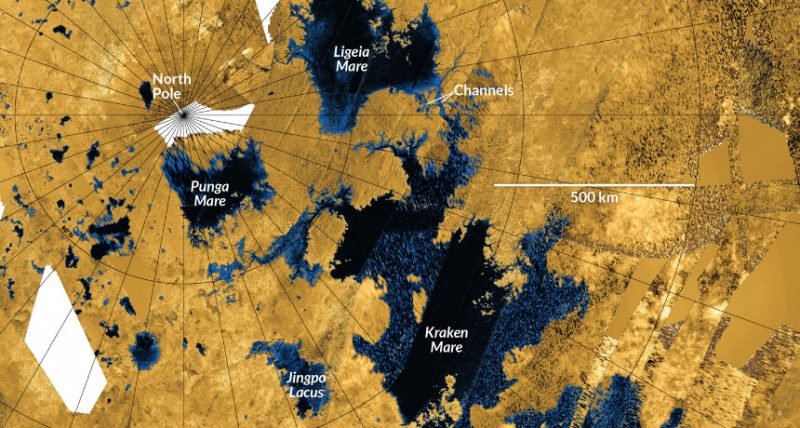

Infrared view of seas and lakes in Titan’s northern hemisphere, taken by Cassini in 2014. Sunlight can be seen glinting off the southern part of Titan’s largest sea, Kraken Mare. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/University of Idaho.

Saturn’s largest moon Titan is the only world in our solar system besides Earth known to have bodies of liquid on its surface. Scientists announced definitive evidence for them in 2007, based on data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. The large ones are known as maria (seas) and the small ones as lacus (lakes). It’s now known that Titan’s hydrologic cycle is surprisingly similar to Earth’s, with one big exception: the liquid on Titan is liquid methane/ethane instead of water, due to the extreme cold. The moon’s northern hemisphere, in particular, has dozens of smaller lakes near its pole, and now scientists have found that they are surprisingly deep and sit on the tops of hills and mesas. These observations come from data collected during the last close flyby of Titan during the Cassini mission, which ended in 2017.

The new peer-reviewed findings were published on April 15, 2019, in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Scientists had thought that the lakes would be an almost equal mixture of methane and ethane, like the larger seas. This is the case with the one sizable lake in the southern hemisphere called Ontario Lacus. But to their surprise, they found that the lakes in the northern hemisphere are composed almost entirely of methane. As lead author Marco Mastrogiuseppe, a Cassini radar scientist at Caltech, explained:

Every time we make discoveries on Titan, Titan becomes more and more mysterious. But these new measurements help give an answer to a few key questions. We can actually now better understand the hydrology of Titan.

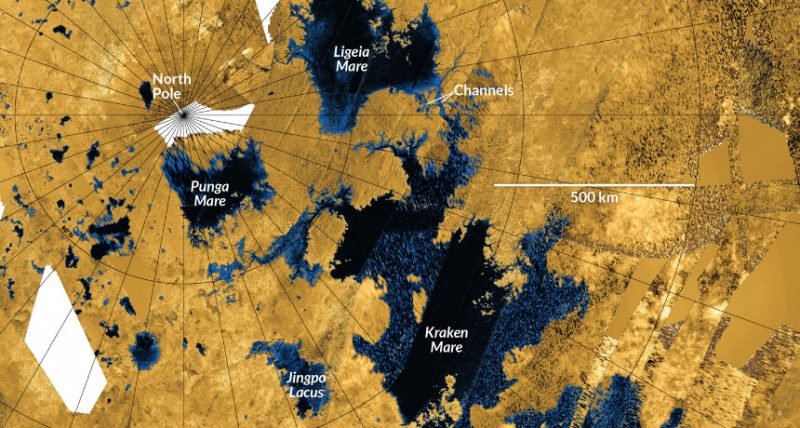

Map of Titan’s seas and lakes in the northern hemisphere. Image via JPL-Caltech/NASA/ASI/USGS.

But while some questions may be answered, other new ones are also raised. Why the difference between the lakes in the northern and southern hemispheres? Also, the hydrology on one side of the northern hemisphere appears to be very different from that on the other side. Why? On the eastern side, you find larger seas with low elevation, canyons and islands. But the western side is dominated by the smaller lakes perched on top of hills and mesas. Some of those lakes are more than 300 feet (100 meters) deep, a surprise given their small sizes. As noted by Cassini scientist and co-author Jonathan Lunine of Cornell University:

It is as if you looked down on the Earth’s North Pole and could see that North America had completely different geologic setting for bodies of liquid than Asia does.

Cenote Sagrado (Sacred Cenote) near Chichen Itza, one of the best known karst lakes (or sinkhole) in Yucatán. Karst lakes are thought to be similar to the deep methane lakes on Titan. Image via Emil Kehnel/Wikipedia/CC BY 3.0.

The findings show how Titan’s alien yet earthly-ish landscape is even more unusual than first thought. They show very deep lakes sitting atop tall mesas or plateaus, suggesting that they formed when the surrounding bedrock of ice and solid organics chemically dissolved and collapsed. These Titan lakes are reminiscent of karst lakes on Earth, which form when subterranean caves collapse. In the earthly counterparts, however, water dissolves limestone, gypsum or dolomite rock.

This is a great example of how – much like the hydrologic cycle – geologic processes on Titan can also mimic those on Earth, yet be uniquely Titanian at the same time. In many ways, Titan looks a lot like Earth, but the underlying mechanisms, and composition of materials, are fundamentally different on this world in the much-colder outer solar system.

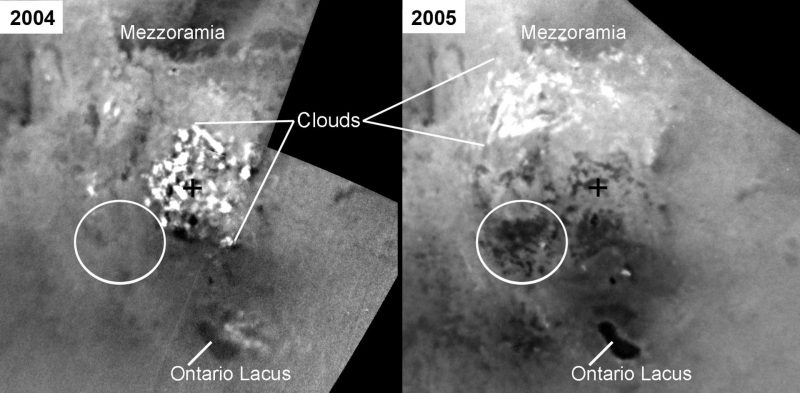

Cassini also observed another kind of lake on Titan. Radar and infrared data revealed transient lakes where the level of liquids varies significantly. These results have been published in a separate paper in Nature Astronomy. According to Shannon MacKenzie, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, those changes may be seasonal:

One possibility is that these transient features could have been shallower bodies of liquid that over the course of the season evaporated and infiltrated into the subsurface.

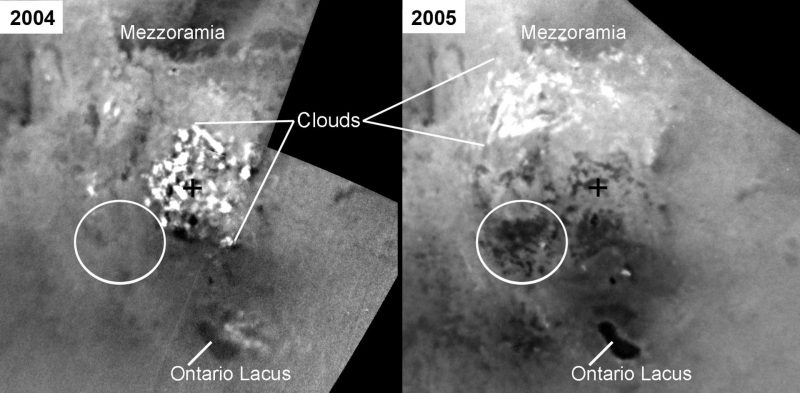

Images from Cassini showing new small lakes appearing in Arrakis Planitia between 2004 and 2005. Such lakes seem to be transient, where the liquids fill the lakes before evaporating or seeping into the ground again. Image via NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

Taken together, the results about both the deep lakes and transient lakes support the scenario where methane/ethane rain feeds the lakes, which then evaporate back into the atmosphere or drain into the subsurface, leaving reservoirs of liquid below the surface. It is a complete hydrologic cycle, but, in the colder environment than on Earth, one where methane and ethane can be liquid and water is in the form of rock-hard ice.

The presence of lakes and seas on Titan brings up another question. Might there possibly be any form of life there? Some scientists think there indeed could be at least microscopic organisms, despite the harsh conditions in contrast to Earth, that use liquid methane/ethane in a similar way that life here uses water. Such life would have to be evolved to exist in conditions unlike any on Earth, but it’s an intriguing possibility.

Bottom line: Data on Titan’s lakes, collected by the Cassini spacecraft (whose mission ended in 2017), continue to reveal insights into a hydrologic cycle that’s remarkably similar to Earth’s in some ways – but distinctly alien in others. A new finding is that lakes near Titan’s north pole are surprisingly deep and sit on the tops of hills and mesas.

Source: Deep and methane-rich lakes on Titan

Source: The case for seasonal surface changes at Titan’s lake district

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2PpZOJV

Infrared view of seas and lakes in Titan’s northern hemisphere, taken by Cassini in 2014. Sunlight can be seen glinting off the southern part of Titan’s largest sea, Kraken Mare. Image via NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/University of Idaho.

Saturn’s largest moon Titan is the only world in our solar system besides Earth known to have bodies of liquid on its surface. Scientists announced definitive evidence for them in 2007, based on data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. The large ones are known as maria (seas) and the small ones as lacus (lakes). It’s now known that Titan’s hydrologic cycle is surprisingly similar to Earth’s, with one big exception: the liquid on Titan is liquid methane/ethane instead of water, due to the extreme cold. The moon’s northern hemisphere, in particular, has dozens of smaller lakes near its pole, and now scientists have found that they are surprisingly deep and sit on the tops of hills and mesas. These observations come from data collected during the last close flyby of Titan during the Cassini mission, which ended in 2017.

The new peer-reviewed findings were published on April 15, 2019, in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Scientists had thought that the lakes would be an almost equal mixture of methane and ethane, like the larger seas. This is the case with the one sizable lake in the southern hemisphere called Ontario Lacus. But to their surprise, they found that the lakes in the northern hemisphere are composed almost entirely of methane. As lead author Marco Mastrogiuseppe, a Cassini radar scientist at Caltech, explained:

Every time we make discoveries on Titan, Titan becomes more and more mysterious. But these new measurements help give an answer to a few key questions. We can actually now better understand the hydrology of Titan.

Map of Titan’s seas and lakes in the northern hemisphere. Image via JPL-Caltech/NASA/ASI/USGS.

But while some questions may be answered, other new ones are also raised. Why the difference between the lakes in the northern and southern hemispheres? Also, the hydrology on one side of the northern hemisphere appears to be very different from that on the other side. Why? On the eastern side, you find larger seas with low elevation, canyons and islands. But the western side is dominated by the smaller lakes perched on top of hills and mesas. Some of those lakes are more than 300 feet (100 meters) deep, a surprise given their small sizes. As noted by Cassini scientist and co-author Jonathan Lunine of Cornell University:

It is as if you looked down on the Earth’s North Pole and could see that North America had completely different geologic setting for bodies of liquid than Asia does.

Cenote Sagrado (Sacred Cenote) near Chichen Itza, one of the best known karst lakes (or sinkhole) in Yucatán. Karst lakes are thought to be similar to the deep methane lakes on Titan. Image via Emil Kehnel/Wikipedia/CC BY 3.0.

The findings show how Titan’s alien yet earthly-ish landscape is even more unusual than first thought. They show very deep lakes sitting atop tall mesas or plateaus, suggesting that they formed when the surrounding bedrock of ice and solid organics chemically dissolved and collapsed. These Titan lakes are reminiscent of karst lakes on Earth, which form when subterranean caves collapse. In the earthly counterparts, however, water dissolves limestone, gypsum or dolomite rock.

This is a great example of how – much like the hydrologic cycle – geologic processes on Titan can also mimic those on Earth, yet be uniquely Titanian at the same time. In many ways, Titan looks a lot like Earth, but the underlying mechanisms, and composition of materials, are fundamentally different on this world in the much-colder outer solar system.

Cassini also observed another kind of lake on Titan. Radar and infrared data revealed transient lakes where the level of liquids varies significantly. These results have been published in a separate paper in Nature Astronomy. According to Shannon MacKenzie, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, those changes may be seasonal:

One possibility is that these transient features could have been shallower bodies of liquid that over the course of the season evaporated and infiltrated into the subsurface.

Images from Cassini showing new small lakes appearing in Arrakis Planitia between 2004 and 2005. Such lakes seem to be transient, where the liquids fill the lakes before evaporating or seeping into the ground again. Image via NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute.

Taken together, the results about both the deep lakes and transient lakes support the scenario where methane/ethane rain feeds the lakes, which then evaporate back into the atmosphere or drain into the subsurface, leaving reservoirs of liquid below the surface. It is a complete hydrologic cycle, but, in the colder environment than on Earth, one where methane and ethane can be liquid and water is in the form of rock-hard ice.

The presence of lakes and seas on Titan brings up another question. Might there possibly be any form of life there? Some scientists think there indeed could be at least microscopic organisms, despite the harsh conditions in contrast to Earth, that use liquid methane/ethane in a similar way that life here uses water. Such life would have to be evolved to exist in conditions unlike any on Earth, but it’s an intriguing possibility.

Bottom line: Data on Titan’s lakes, collected by the Cassini spacecraft (whose mission ended in 2017), continue to reveal insights into a hydrologic cycle that’s remarkably similar to Earth’s in some ways – but distinctly alien in others. A new finding is that lakes near Titan’s north pole are surprisingly deep and sit on the tops of hills and mesas.

Source: Deep and methane-rich lakes on Titan

Source: The case for seasonal surface changes at Titan’s lake district

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2PpZOJV

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire