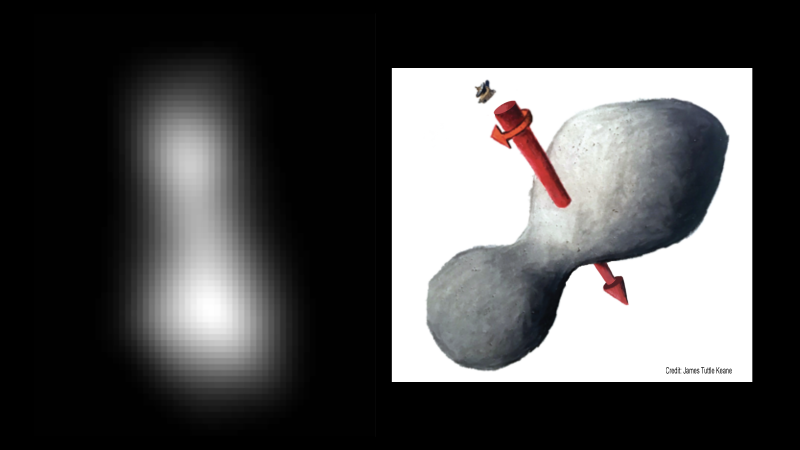

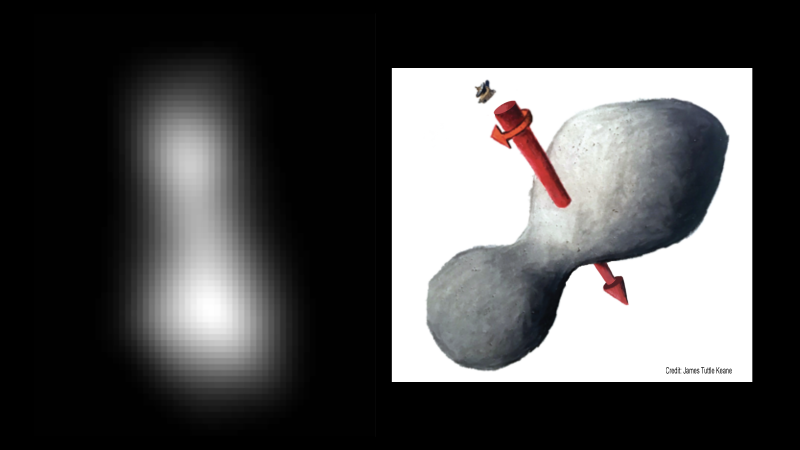

Left, a composite of 2 images taken via New Horizons. Scientists say it provides the best indication of Ultima Thule’s size and shape so far. Preliminary measurements of this Kuiper Belt object suggest it’s approximately 20 miles long by 10 miles wide (32 km by 16 km). Right, an artist’s impression of one possible appearance of Ultima Thule, based on the actual image at left. The direction of Ultima’s spin axis is indicated by the arrows. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI; sketch courtesy of James Tuttle Keane.

The New Year has brought with it a couple of astounding new space records. On December 31, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft successfully moved into orbit around the smallest space body yet, a near-Earth asteroid called Bennu. Just hours later, in the early hours of New Year’s Day according to clocks in the Americas, the New Horizons spacecraft – also a NASA craft, launched from Earth in 2006 and made famous in 2015 for its once-in-a-lifetime encounter with Pluto – made history again with the most distant spacecraft encounter yet. New Horizons swept past an object in the Kuiper Belt – known as Ultima Thule – on January 1, 2019 at 06:33 UTC (12:33 a.m. EST).

Signals confirming the spacecraft had survived the encounter and had filled its digital recorders with science data on Ultima Thule reached the mission operations center at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland almost exactly 10 hours later, at 14:29 UTC (10:29 a.m. EST).

It took that long for New Horizons to send back its data from this distant object, some 4 billion miles from our sun.

New Horizons team members awaiting a signal from New Horizons, at the Mission Operations Center of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, on January 1, 2019. Photo via NASA Flickr/Bill Ingalls.

New Horizons’ path took it about 2,200 miles (3,500 km) from Ultima Thule (which, by the way, is officially designated 2014 MU69). The decision to take that path – instead of a hazard-avoiding detour that would have pushed it three times farther out – was made as recently as mid-December. Space scientists made the decision only after observations from New Horizons itself revealed no rings, no small moons, no potential hazards, in Ultima Thule’s vicinity.

Still, space scientists couldn’t be sure the spacecraft would survive the encounter. They at times looked tense while awaiting word from the spacecraft’s various systems. Then, one by one, all were confirmed as healthy and the mood turned jubilant.

The images on this page are just preliminary. New Horizons spacecraft will continue downloading images and other data in the days and months ahead, completing the return of all science data over the next 20 months.

Updated view of #UltimaThule based on better imagery from @NASANewHorizons … 35 km x 15 km with dogbone shape. #UltimaFlyby pic.twitter.com/QiAHECPfZN

— Alan Boyle (@b0yle) January 1, 2019

Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said:

New Horizons performed as planned today, conducting the farthest exploration of any world in history … The data we have look fantastic and we’re already learning about Ultima from up close. From here out the data will just get better and better!

Prior to the encounter, scientists had been puzzling over the light reflected from Ultima Thule. The spacecraft had been taking hundreds of images to measure Ultima’s brightness, but those recent measurements appeared to be at odds with a 2017 observation, made when Ultima Thule covered (occulted) a star as seen from Earth. In 2017, based on the occultation data, scientists thought Ultima Thule might be not one, but two bodies orbiting around each other. If there aren’t two objects there, the science team said in 2017, then this little Kuiper Belt object might have a pronounced elongated shape.

And indeed its shape does appear elongated, although more is sure to be revealed about its shape and spin axis in the days ahead. For now, images taken during the spacecraft’s approach show that Ultima Thule might have a shape similar to a bowling pin, spinning end over end, with dimensions of approximately 20 by 10 miles (32 by 16 km).

Flyby data have already solved one of Ultima’s mysteries, showing that the Kuiper Belt object is spinning like a propeller with the axis pointing approximately toward New Horizons. This explains why, in earlier images taken before Ultima was resolved, its brightness didn’t appear to vary as it rotated.

The team has still not determined Ultima Thule’s rotation period.

As the science data began its initial return to Earth, mission team members and leadership reveled in the excitement of the first exploration of this distant region of space. Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory Director Ralph Semmel commented:

New Horizons holds a dear place in our hearts as an intrepid and persistent little explorer, as well as a great photographer. This flyby marks a first for all of us — APL, NASA, the nation and the world — and it is a great credit to the bold team of scientists and engineers who brought us to this point.

Now, almost 13 years after the launch of New Horizons, scientists say the spacecraft will continue its exploration of the Kuiper Belt until at least 2021. Team members plan to propose more Kuiper Belt exploration.

Bottom line: Since encountering Pluto in 2015, New Horizons has been heading outward. It’s now survived a sweep past its next target, Ultima Thule, now the most distant object visited by a spacecraft from Earth.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2R1v9X3

Left, a composite of 2 images taken via New Horizons. Scientists say it provides the best indication of Ultima Thule’s size and shape so far. Preliminary measurements of this Kuiper Belt object suggest it’s approximately 20 miles long by 10 miles wide (32 km by 16 km). Right, an artist’s impression of one possible appearance of Ultima Thule, based on the actual image at left. The direction of Ultima’s spin axis is indicated by the arrows. Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI; sketch courtesy of James Tuttle Keane.

The New Year has brought with it a couple of astounding new space records. On December 31, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx spacecraft successfully moved into orbit around the smallest space body yet, a near-Earth asteroid called Bennu. Just hours later, in the early hours of New Year’s Day according to clocks in the Americas, the New Horizons spacecraft – also a NASA craft, launched from Earth in 2006 and made famous in 2015 for its once-in-a-lifetime encounter with Pluto – made history again with the most distant spacecraft encounter yet. New Horizons swept past an object in the Kuiper Belt – known as Ultima Thule – on January 1, 2019 at 06:33 UTC (12:33 a.m. EST).

Signals confirming the spacecraft had survived the encounter and had filled its digital recorders with science data on Ultima Thule reached the mission operations center at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland almost exactly 10 hours later, at 14:29 UTC (10:29 a.m. EST).

It took that long for New Horizons to send back its data from this distant object, some 4 billion miles from our sun.

New Horizons team members awaiting a signal from New Horizons, at the Mission Operations Center of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, on January 1, 2019. Photo via NASA Flickr/Bill Ingalls.

New Horizons’ path took it about 2,200 miles (3,500 km) from Ultima Thule (which, by the way, is officially designated 2014 MU69). The decision to take that path – instead of a hazard-avoiding detour that would have pushed it three times farther out – was made as recently as mid-December. Space scientists made the decision only after observations from New Horizons itself revealed no rings, no small moons, no potential hazards, in Ultima Thule’s vicinity.

Still, space scientists couldn’t be sure the spacecraft would survive the encounter. They at times looked tense while awaiting word from the spacecraft’s various systems. Then, one by one, all were confirmed as healthy and the mood turned jubilant.

The images on this page are just preliminary. New Horizons spacecraft will continue downloading images and other data in the days and months ahead, completing the return of all science data over the next 20 months.

Updated view of #UltimaThule based on better imagery from @NASANewHorizons … 35 km x 15 km with dogbone shape. #UltimaFlyby pic.twitter.com/QiAHECPfZN

— Alan Boyle (@b0yle) January 1, 2019

Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said:

New Horizons performed as planned today, conducting the farthest exploration of any world in history … The data we have look fantastic and we’re already learning about Ultima from up close. From here out the data will just get better and better!

Prior to the encounter, scientists had been puzzling over the light reflected from Ultima Thule. The spacecraft had been taking hundreds of images to measure Ultima’s brightness, but those recent measurements appeared to be at odds with a 2017 observation, made when Ultima Thule covered (occulted) a star as seen from Earth. In 2017, based on the occultation data, scientists thought Ultima Thule might be not one, but two bodies orbiting around each other. If there aren’t two objects there, the science team said in 2017, then this little Kuiper Belt object might have a pronounced elongated shape.

And indeed its shape does appear elongated, although more is sure to be revealed about its shape and spin axis in the days ahead. For now, images taken during the spacecraft’s approach show that Ultima Thule might have a shape similar to a bowling pin, spinning end over end, with dimensions of approximately 20 by 10 miles (32 by 16 km).

Flyby data have already solved one of Ultima’s mysteries, showing that the Kuiper Belt object is spinning like a propeller with the axis pointing approximately toward New Horizons. This explains why, in earlier images taken before Ultima was resolved, its brightness didn’t appear to vary as it rotated.

The team has still not determined Ultima Thule’s rotation period.

As the science data began its initial return to Earth, mission team members and leadership reveled in the excitement of the first exploration of this distant region of space. Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory Director Ralph Semmel commented:

New Horizons holds a dear place in our hearts as an intrepid and persistent little explorer, as well as a great photographer. This flyby marks a first for all of us — APL, NASA, the nation and the world — and it is a great credit to the bold team of scientists and engineers who brought us to this point.

Now, almost 13 years after the launch of New Horizons, scientists say the spacecraft will continue its exploration of the Kuiper Belt until at least 2021. Team members plan to propose more Kuiper Belt exploration.

Bottom line: Since encountering Pluto in 2015, New Horizons has been heading outward. It’s now survived a sweep past its next target, Ultima Thule, now the most distant object visited by a spacecraft from Earth.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2R1v9X3

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire