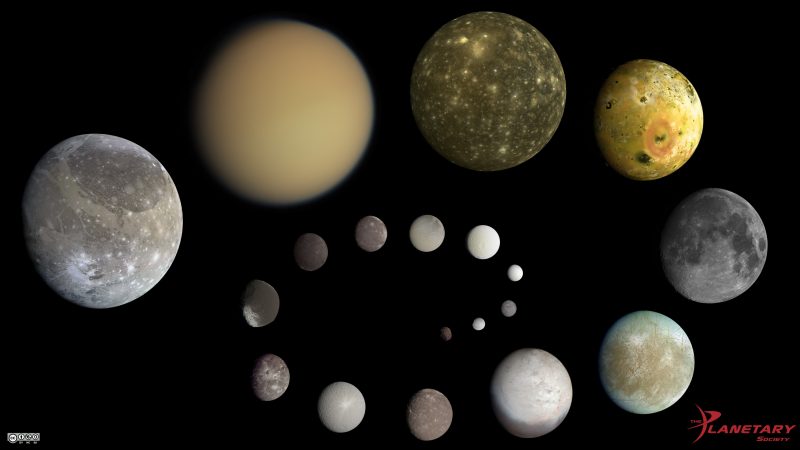

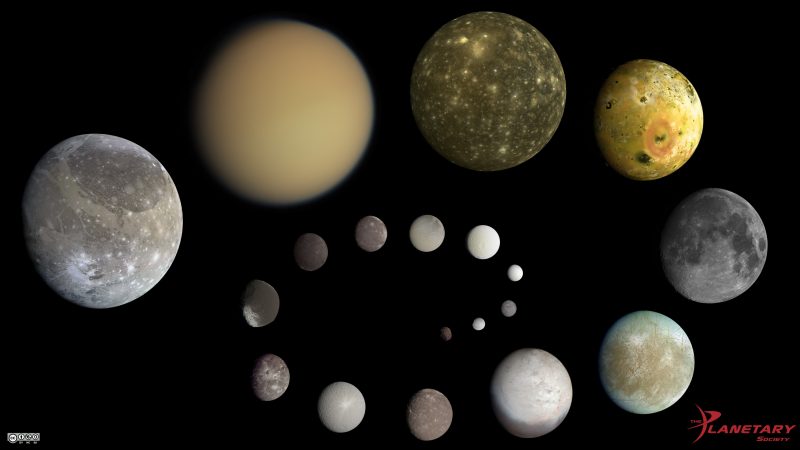

Size comparison of the major moons in our solar system via Emily Lakdawalla.

Most of the planets in our solar system have orbiting moons, and even some asteroids have their own moons. But do any moons have moons? Is it possible? Could there be so-called submoons? Carnegie Science’s Juna Kollmeier said her 4-year-old son sparked her interest in this subject by asking this seemingly logical question. It’s a simple enough question. If most other objects in the solar system can have moons, why not moons themselves?

Kollmeier decided to try to answer the question, along with her colleague Sean Raymond of Université de Bordeaux. Their results have now been published in a new peer-reviewed paper in the February 2019 issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

As explained by Raymond in a statement from Carnegie Science:

Planets orbit stars and moons orbit planets, so it was natural to ask if smaller moons could orbit larger ones.

So far at least, no submoons have been found orbiting any of the moons considered most likely to support them – Jupiter’s moon Callisto, Saturn’s moons Titan and Iapetus and Earth’s own moon. According to Kollmeier:

The lack of known submoons in our solar system, even orbiting around moons that could theoretically support such objects, can offer us clues about how our own and neighboring planets formed, about which there are still many outstanding questions.

Earth’s moon should theoretically be able to have its own moon. Why doesn’t it? Image via NASA/Goddard.

The researchers found that only large moons on wide orbits from their host planets would be capable of hosting submoons. Usually, any submoons orbiting smaller moons closer to their planet would have their orbits destabilized by tidal forces. Jupiter’s large moon Callisto, Saturn’s large moon Titan, another Saturn moon called Iapetus and Earth’s moon could all theoretically have submoons, so why don’t they?

There may be other sources of submoon instability, such as the non-uniform concentration of mass in Earth’s moon’s crust, according to the researchers.

Even asteroids can have moons, such as 2004 BL86. It is about 1,100 feet (325 meters) in diameter, and its moon is tiny, only 230 feet (70 meters) wide. Image via NASA.

Part of the answer might also have to do with how the primary moons formed in the first place. Earth’s moon is thought to have been born out of a collision between Earth and another body about the size of Mars – and that collisions may have helped life on Earth to get started. But some other moons, like those orbiting Jupiter and Saturn, originated from the same cloud of gas and dust that the planets themselves formed from. Kollmeier added:

And, of course, this could inform ongoing efforts to understand how planetary systems evolve elsewhere and how our own solar system fits into the thousands of others discovered by planet-hunting missions.

It may be that in many or even most cases, there are multiple factors that make the orbits of submoons inherently unstable. Knowing whether that is true or not may have to wait for discoveries of moons orbiting distant exoplanets. Moons themselves are much harder to detect and only one promising candidate has been found so far – a possible exomoon orbiting the Jupiter-sized exoplanet Kepler-1625b. That possible moon – about the size of Neptune – is large enough and far enough from its planet that submoons should be possible as well. Astronomers will need to verify that primary moon first – if it does exist – before looking for any submoons.

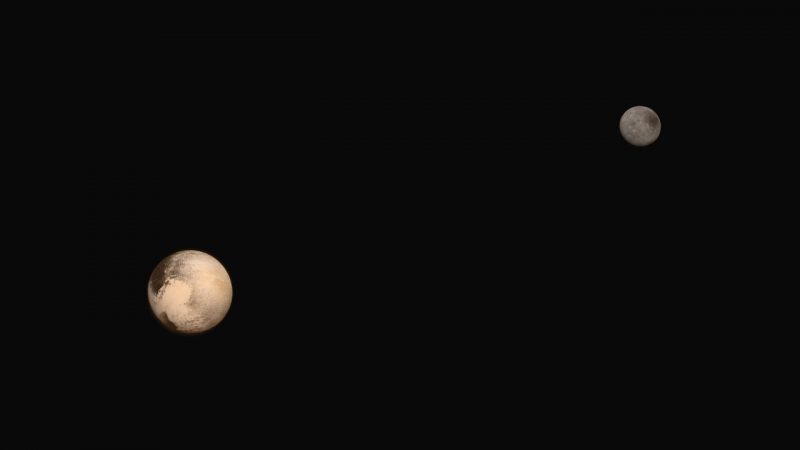

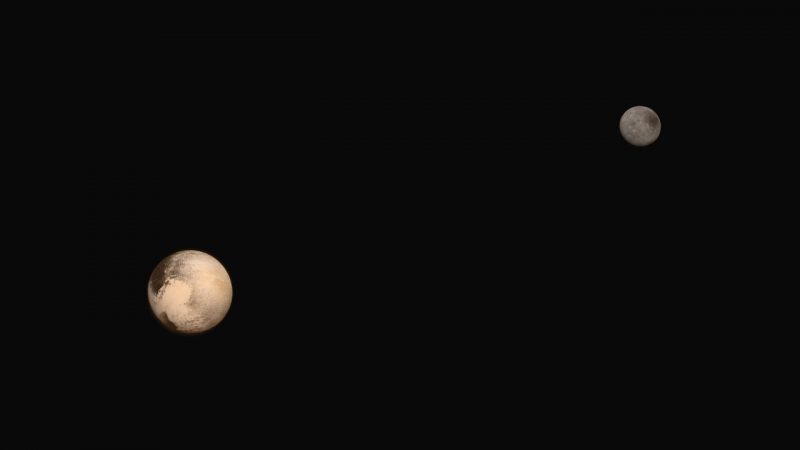

Even little Pluto has five moons, including the largest one – Charon – shown here. So how many moons with their own moons could there be out there? Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SWRI.

Even though Earth’s moon doesn’t have a submoon now, it may in the future, according to the researchers – an artificial one, perhaps NASA’s planned Lunar Gateway. The Lunar Gateway would help to establish humanity’s presence in deep space, as outlined by William Gerstenmaier, associate administrator of Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters:

The Gateway will give us a strategic presence in cislunar space. It will drive our activity with commercial and international partners and help us explore the Moon and its resources. We will ultimately translate that experience toward human missions to Mars.

Raymond has also written a cool poem about moons having moons, which you can enjoy on his blog here.

Bottom line: The possibility of moons having their own moons is a fascinating one, even though we haven’t found any examples yet. This new research from Carnegie Science shows that it is indeed possible, but only under the right circumstances.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2TfVhL8

Size comparison of the major moons in our solar system via Emily Lakdawalla.

Most of the planets in our solar system have orbiting moons, and even some asteroids have their own moons. But do any moons have moons? Is it possible? Could there be so-called submoons? Carnegie Science’s Juna Kollmeier said her 4-year-old son sparked her interest in this subject by asking this seemingly logical question. It’s a simple enough question. If most other objects in the solar system can have moons, why not moons themselves?

Kollmeier decided to try to answer the question, along with her colleague Sean Raymond of Université de Bordeaux. Their results have now been published in a new peer-reviewed paper in the February 2019 issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

As explained by Raymond in a statement from Carnegie Science:

Planets orbit stars and moons orbit planets, so it was natural to ask if smaller moons could orbit larger ones.

So far at least, no submoons have been found orbiting any of the moons considered most likely to support them – Jupiter’s moon Callisto, Saturn’s moons Titan and Iapetus and Earth’s own moon. According to Kollmeier:

The lack of known submoons in our solar system, even orbiting around moons that could theoretically support such objects, can offer us clues about how our own and neighboring planets formed, about which there are still many outstanding questions.

Earth’s moon should theoretically be able to have its own moon. Why doesn’t it? Image via NASA/Goddard.

The researchers found that only large moons on wide orbits from their host planets would be capable of hosting submoons. Usually, any submoons orbiting smaller moons closer to their planet would have their orbits destabilized by tidal forces. Jupiter’s large moon Callisto, Saturn’s large moon Titan, another Saturn moon called Iapetus and Earth’s moon could all theoretically have submoons, so why don’t they?

There may be other sources of submoon instability, such as the non-uniform concentration of mass in Earth’s moon’s crust, according to the researchers.

Even asteroids can have moons, such as 2004 BL86. It is about 1,100 feet (325 meters) in diameter, and its moon is tiny, only 230 feet (70 meters) wide. Image via NASA.

Part of the answer might also have to do with how the primary moons formed in the first place. Earth’s moon is thought to have been born out of a collision between Earth and another body about the size of Mars – and that collisions may have helped life on Earth to get started. But some other moons, like those orbiting Jupiter and Saturn, originated from the same cloud of gas and dust that the planets themselves formed from. Kollmeier added:

And, of course, this could inform ongoing efforts to understand how planetary systems evolve elsewhere and how our own solar system fits into the thousands of others discovered by planet-hunting missions.

It may be that in many or even most cases, there are multiple factors that make the orbits of submoons inherently unstable. Knowing whether that is true or not may have to wait for discoveries of moons orbiting distant exoplanets. Moons themselves are much harder to detect and only one promising candidate has been found so far – a possible exomoon orbiting the Jupiter-sized exoplanet Kepler-1625b. That possible moon – about the size of Neptune – is large enough and far enough from its planet that submoons should be possible as well. Astronomers will need to verify that primary moon first – if it does exist – before looking for any submoons.

Even little Pluto has five moons, including the largest one – Charon – shown here. So how many moons with their own moons could there be out there? Image via NASA/JHUAPL/SWRI.

Even though Earth’s moon doesn’t have a submoon now, it may in the future, according to the researchers – an artificial one, perhaps NASA’s planned Lunar Gateway. The Lunar Gateway would help to establish humanity’s presence in deep space, as outlined by William Gerstenmaier, associate administrator of Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters:

The Gateway will give us a strategic presence in cislunar space. It will drive our activity with commercial and international partners and help us explore the Moon and its resources. We will ultimately translate that experience toward human missions to Mars.

Raymond has also written a cool poem about moons having moons, which you can enjoy on his blog here.

Bottom line: The possibility of moons having their own moons is a fascinating one, even though we haven’t found any examples yet. This new research from Carnegie Science shows that it is indeed possible, but only under the right circumstances.

from EarthSky http://bit.ly/2TfVhL8

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire