Photo: Lyrid meteor 2013 by Mike O’Neal

Late Sunday night (April 22, 2018) or before dawn Monday might offer you a few Lyrid meteors, but we’re past the peak of the shower at these times. Plus – as the Lyrids wane – the moon is waxing larger and staying in the sky for more of the night. Try watching after the moon has set on Monday morning, April 23. You might – or might not – see a smattering of meteors.

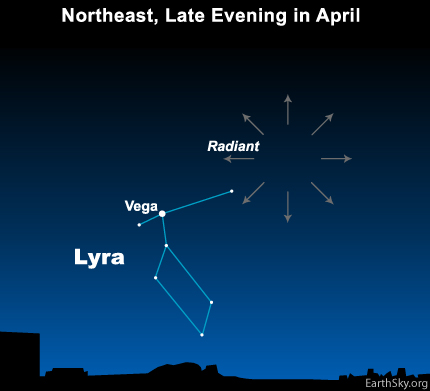

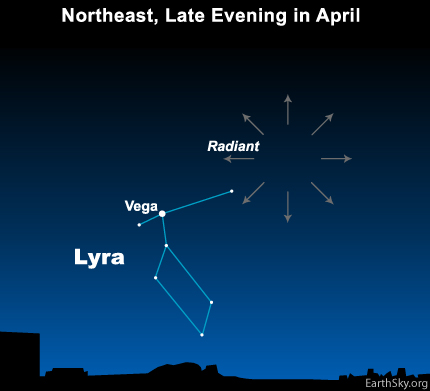

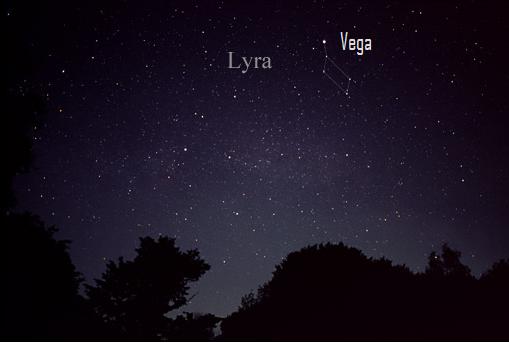

If you trace the paths of Lyrid meteors backward, you’ll see they radiate from the constellation Lyra the Harp, near the brilliant star Vega. It’s from Vega’s constellation Lyra that the Lyrid meteor shower takes its name.

You don’t need to identify Vega or its constellation Lyra in order to watch the Lyrid meteor shower. Any meteors you see will appear unexpectedly, in any and all parts of the sky.

Be aware that the star Vega resides quite far north of the celestial equator. That’s why the Lyrid meteor shower favors the Northern Hemisphere.

The radiant point of the Lyrid meteor shower is near the bright star Vega in the constellation Lyra the Harp. Read more about the Lyrid’s radiant point.

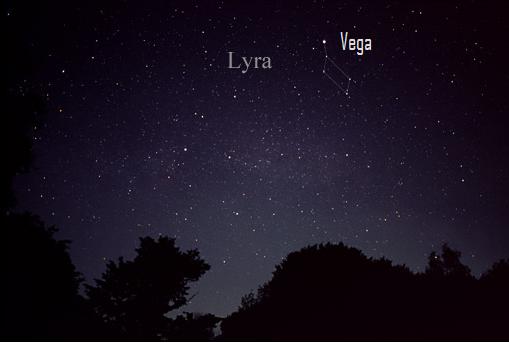

Another view of the brilliant star Vega, which nearly coincides with the radiant point of April’s Lyrid meteor shower. Image via AlltheSky.

Around the Lyrids’ peak, the star Vega rises above your local horizon – in the northeast – around 9 to 10 p.m. local time (that’s the time on your clock, from Northern Hemisphere locations). It climbs upward through the night. By midnight, Vega is high enough in the sky that meteors radiating from her direction streak across your sky.

Just before dawn, Vega and the radiant point shine high overhead. That’s one reason the meteors are always more numerous before dawn.

Portrait of Confucius.

The Lyrid meteor shower has the distinction of being among the oldest of known meteor showers. Records of this shower go back for some 2,700 years.

The ancient Chinese are said to have observed the Lyrid meteors “falling like rain” in the year 687 B.C.

That time period in ancient China, by the way, corresponds with what is called the Spring and Autumn Period (about 771 to 476 B.C.), which tradition associates with the Chinese teacher and philosopher Confucius, one of the first to espouse the principle: “Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself.”

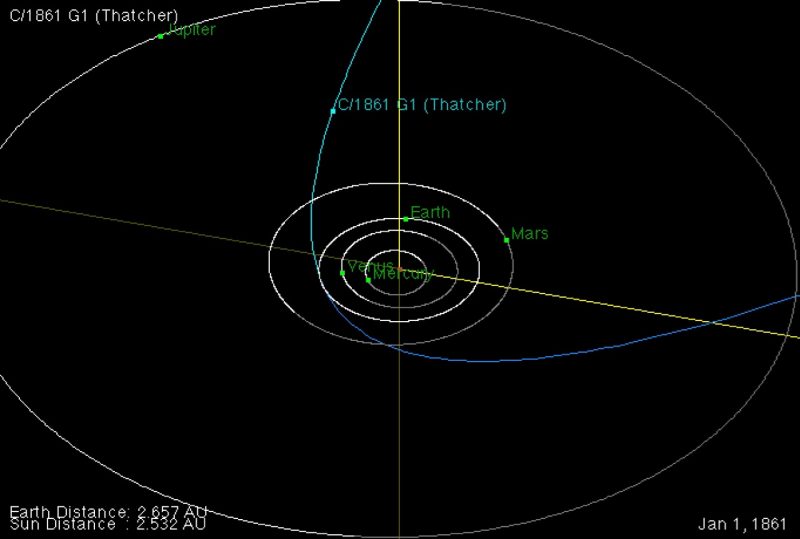

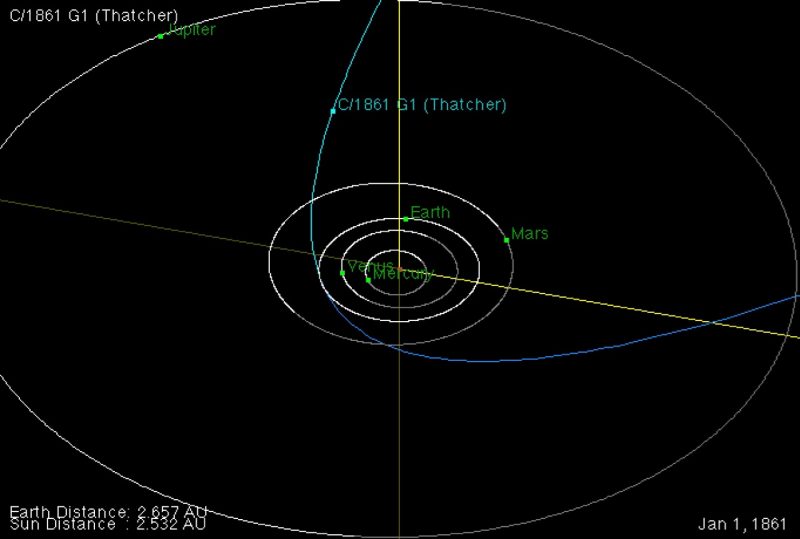

Comet Thatcher on January 1, 1861, the year of its last (and only) observed return. Image via JPL Small-Body Database.

Why do we see a meteor shower at this time of year? Every year, in the later part of April, our planet Earth crosses the orbital path of Comet Thatcher (C/1861 G1), of which there are no photographs due to its roughly 415-year orbit around the sun. Comet Thatcher last visited the inner solar system in 1861, before the photographic process became widespread.

This comet isn’t expected to return until the year 2276.

Bits and pieces shed by this comet litter its orbit and bombard the Earth’s upper atmosphere at 110,000 miles (177,000 km) per hour. The vaporizing debris streaks the nighttime with medium-fast Lyrid meteors.

It’s when Earth passes through an unusually thick clump of comet rubble that an elevated number of meteors can be seen.

Bottom line: The Lyrid meteor shower offers 10 to 20 meteors per hour at its peak on a moonless night. The peak numbers are expected to fall on the morning of April 22. Try watching on April 21 and 23, too. In 2018, the light of the waxing moon won’t greatly interfere with the Lyrid shower, because it’ll set before the peak viewing hours. In rare instances, Lyrid meteors can bombard the sky with up to nearly 100 meteors per hour. No Lyrid meteor storm is expected this year … but you never know.

EarthSky’s meteor shower guide for 2018

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2vG6nlo

Photo: Lyrid meteor 2013 by Mike O’Neal

Late Sunday night (April 22, 2018) or before dawn Monday might offer you a few Lyrid meteors, but we’re past the peak of the shower at these times. Plus – as the Lyrids wane – the moon is waxing larger and staying in the sky for more of the night. Try watching after the moon has set on Monday morning, April 23. You might – or might not – see a smattering of meteors.

If you trace the paths of Lyrid meteors backward, you’ll see they radiate from the constellation Lyra the Harp, near the brilliant star Vega. It’s from Vega’s constellation Lyra that the Lyrid meteor shower takes its name.

You don’t need to identify Vega or its constellation Lyra in order to watch the Lyrid meteor shower. Any meteors you see will appear unexpectedly, in any and all parts of the sky.

Be aware that the star Vega resides quite far north of the celestial equator. That’s why the Lyrid meteor shower favors the Northern Hemisphere.

The radiant point of the Lyrid meteor shower is near the bright star Vega in the constellation Lyra the Harp. Read more about the Lyrid’s radiant point.

Another view of the brilliant star Vega, which nearly coincides with the radiant point of April’s Lyrid meteor shower. Image via AlltheSky.

Around the Lyrids’ peak, the star Vega rises above your local horizon – in the northeast – around 9 to 10 p.m. local time (that’s the time on your clock, from Northern Hemisphere locations). It climbs upward through the night. By midnight, Vega is high enough in the sky that meteors radiating from her direction streak across your sky.

Just before dawn, Vega and the radiant point shine high overhead. That’s one reason the meteors are always more numerous before dawn.

Portrait of Confucius.

The Lyrid meteor shower has the distinction of being among the oldest of known meteor showers. Records of this shower go back for some 2,700 years.

The ancient Chinese are said to have observed the Lyrid meteors “falling like rain” in the year 687 B.C.

That time period in ancient China, by the way, corresponds with what is called the Spring and Autumn Period (about 771 to 476 B.C.), which tradition associates with the Chinese teacher and philosopher Confucius, one of the first to espouse the principle: “Do not do to others what you do not want done to yourself.”

Comet Thatcher on January 1, 1861, the year of its last (and only) observed return. Image via JPL Small-Body Database.

Why do we see a meteor shower at this time of year? Every year, in the later part of April, our planet Earth crosses the orbital path of Comet Thatcher (C/1861 G1), of which there are no photographs due to its roughly 415-year orbit around the sun. Comet Thatcher last visited the inner solar system in 1861, before the photographic process became widespread.

This comet isn’t expected to return until the year 2276.

Bits and pieces shed by this comet litter its orbit and bombard the Earth’s upper atmosphere at 110,000 miles (177,000 km) per hour. The vaporizing debris streaks the nighttime with medium-fast Lyrid meteors.

It’s when Earth passes through an unusually thick clump of comet rubble that an elevated number of meteors can be seen.

Bottom line: The Lyrid meteor shower offers 10 to 20 meteors per hour at its peak on a moonless night. The peak numbers are expected to fall on the morning of April 22. Try watching on April 21 and 23, too. In 2018, the light of the waxing moon won’t greatly interfere with the Lyrid shower, because it’ll set before the peak viewing hours. In rare instances, Lyrid meteors can bombard the sky with up to nearly 100 meteors per hour. No Lyrid meteor storm is expected this year … but you never know.

EarthSky’s meteor shower guide for 2018

from EarthSky https://ift.tt/2vG6nlo

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire