By Carol Clark

The laws for how granular materials flow apply even at the giant, geophysical scale of icebergs piling up in the ocean at the outlet of a glacier, scientists have shown.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) published the findings, describing the dynamics of the clog of icebergs — known as an ice mélange — in front of Greenland’s Jakobshavn Glacier. The fast-moving glacier is considered a bellwether for the effects of climate change.

“We’ve connected microscopic theories for the mechanics of granular flowing with the world’s largest granular material — a glacial ice mélange,” says Justin Burton, a physicist at Emory University and lead author of the paper. “Our results could help researchers who are trying to understand the future evolution of the Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets. We’ve showed that an ice mélange could potentially have a large and measurable effect on the production of large icebergs by a glacier.”

The National Science Foundation funded the research, which brought together physicists who study the fundamental mechanics of granular materials in laboratories and glaciologists who spend their summers exploring polar ice sheets.

“Glaciologists generally deal with slow, steady deformation of glacial ice, which behaves like thick molasses — a viscous material creeping towards the sea,” says co-author Jason Amundson, a glaciologist at the University of Alaska Southeast, Juneau. “Ice mélange, on the other hand, is fundamentally a granular material — essentially a giant slushy — that is governed by different physics. We wanted to understand the behavior of ice mélange and its effects on glaciers.”

For thousands of years, the massive glaciers of Earth’s polar regions have remained relatively stable, the ice locked into mountainous shapes that ebbed in warmer months but gained back their bulk in winter. In recent decades, however, warmer temperatures have started rapidly thawing these frozen giants. It’s becoming more common for sheets of ice — some one kilometer tall — to shift, crack and tumble into the sea, splitting from their mother glaciers in an explosive process known as calving.

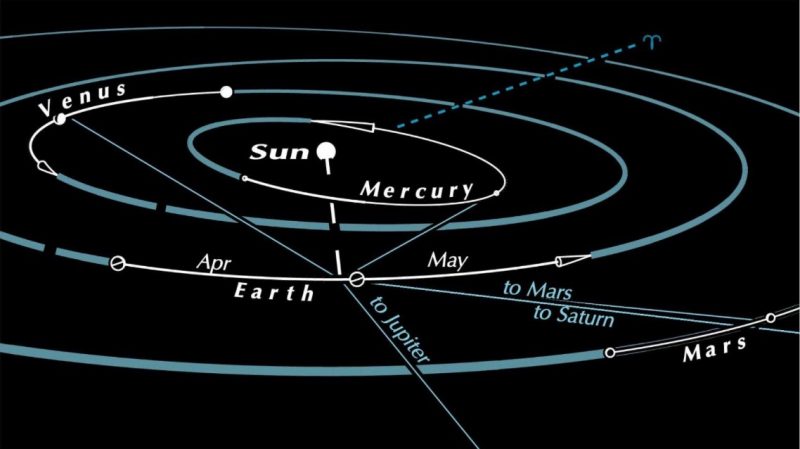

Jakobshavn Glacier is advancing as fast as 50 meters per day until it reaches the ocean edge, a point known as the glacier terminus. About 35 billion tons of icebergs calve off of Jakobshavn Glacier each year, spilling out into Greenland’s Ilulissat fjord, a rocky channel that is about five kilometers wide. The calving process creates a tumbling mix of icebergs which are slowly pushed through the fjord by the motion of the glacier. The ice mélange can extend hundreds of meters deep into the water but on the surface it resembles a lumpy field of snow which inhibits, but cannot stop, the motion of the glacier.

“An ice mélange is kind of like purgatory for icebergs, because they’ve broken off into the water but they haven’t yet made it out to open ocean,” Burton says.

While scientists have long studied how ice forms, breaks and flows within a glacier, no one had quantified the granular flow of an ice mélange. It was an irresistible challenge to Burton. His lab creates experimental models of glacial processes to try to quantify their physical forces. It also uses microscopic particles as a model to understand the fundamental mechanics of granular, amorphous materials, and the boundary between a free-flowing state and a rigid, jammed-up one.

“Granular material is everywhere, from the powders that make up pharmaceuticals to the sand, dirt and rocks that shape our Earth,” Burton says. And yet, he adds, the properties of these amorphous materials are not as well understood as those of liquids or crystals.

In addition to Amundson, Burton’s co-authors on the PNAS paper include glaciologist Ryan Cassotto — formerly with the University of New Hampshire and now with the University of Colorado Boulder — and physicists Chin-Chang Kuo and Michael Dennin, from the University of California, Irvine.

The researchers characterized both the flow and mechanical stress of the Jacobshavn ice mélange using field measurements, satellite data, lab experiments and numerical modeling. The results quantitatively describe the flow of the ice mélange as it jams and unjams during its journey through the fjord.

The paper also showed how the ice mélange can act as a “granular ice shelf” in its jammed state, buttressing even the largest icebergs calved into the ocean.

“We’ve shown that glaciologists modeling the behavior of ice shelves with ice mélanges should factor in the forces of those mélanges,” Burton says. “We’ve provided them with the quantitative tools to do so.”

Related:

The physics of a glacial earthquake

How lifeless particles can become 'life-like' by switching behaviors

from eScienceCommons https://ift.tt/2rdhgVY

By Carol Clark

The laws for how granular materials flow apply even at the giant, geophysical scale of icebergs piling up in the ocean at the outlet of a glacier, scientists have shown.

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) published the findings, describing the dynamics of the clog of icebergs — known as an ice mélange — in front of Greenland’s Jakobshavn Glacier. The fast-moving glacier is considered a bellwether for the effects of climate change.

“We’ve connected microscopic theories for the mechanics of granular flowing with the world’s largest granular material — a glacial ice mélange,” says Justin Burton, a physicist at Emory University and lead author of the paper. “Our results could help researchers who are trying to understand the future evolution of the Greenland and Antarctica ice sheets. We’ve showed that an ice mélange could potentially have a large and measurable effect on the production of large icebergs by a glacier.”

The National Science Foundation funded the research, which brought together physicists who study the fundamental mechanics of granular materials in laboratories and glaciologists who spend their summers exploring polar ice sheets.

“Glaciologists generally deal with slow, steady deformation of glacial ice, which behaves like thick molasses — a viscous material creeping towards the sea,” says co-author Jason Amundson, a glaciologist at the University of Alaska Southeast, Juneau. “Ice mélange, on the other hand, is fundamentally a granular material — essentially a giant slushy — that is governed by different physics. We wanted to understand the behavior of ice mélange and its effects on glaciers.”

For thousands of years, the massive glaciers of Earth’s polar regions have remained relatively stable, the ice locked into mountainous shapes that ebbed in warmer months but gained back their bulk in winter. In recent decades, however, warmer temperatures have started rapidly thawing these frozen giants. It’s becoming more common for sheets of ice — some one kilometer tall — to shift, crack and tumble into the sea, splitting from their mother glaciers in an explosive process known as calving.

Jakobshavn Glacier is advancing as fast as 50 meters per day until it reaches the ocean edge, a point known as the glacier terminus. About 35 billion tons of icebergs calve off of Jakobshavn Glacier each year, spilling out into Greenland’s Ilulissat fjord, a rocky channel that is about five kilometers wide. The calving process creates a tumbling mix of icebergs which are slowly pushed through the fjord by the motion of the glacier. The ice mélange can extend hundreds of meters deep into the water but on the surface it resembles a lumpy field of snow which inhibits, but cannot stop, the motion of the glacier.

“An ice mélange is kind of like purgatory for icebergs, because they’ve broken off into the water but they haven’t yet made it out to open ocean,” Burton says.

While scientists have long studied how ice forms, breaks and flows within a glacier, no one had quantified the granular flow of an ice mélange. It was an irresistible challenge to Burton. His lab creates experimental models of glacial processes to try to quantify their physical forces. It also uses microscopic particles as a model to understand the fundamental mechanics of granular, amorphous materials, and the boundary between a free-flowing state and a rigid, jammed-up one.

“Granular material is everywhere, from the powders that make up pharmaceuticals to the sand, dirt and rocks that shape our Earth,” Burton says. And yet, he adds, the properties of these amorphous materials are not as well understood as those of liquids or crystals.

In addition to Amundson, Burton’s co-authors on the PNAS paper include glaciologist Ryan Cassotto — formerly with the University of New Hampshire and now with the University of Colorado Boulder — and physicists Chin-Chang Kuo and Michael Dennin, from the University of California, Irvine.

The researchers characterized both the flow and mechanical stress of the Jacobshavn ice mélange using field measurements, satellite data, lab experiments and numerical modeling. The results quantitatively describe the flow of the ice mélange as it jams and unjams during its journey through the fjord.

The paper also showed how the ice mélange can act as a “granular ice shelf” in its jammed state, buttressing even the largest icebergs calved into the ocean.

“We’ve shown that glaciologists modeling the behavior of ice shelves with ice mélanges should factor in the forces of those mélanges,” Burton says. “We’ve provided them with the quantitative tools to do so.”

Related:

The physics of a glacial earthquake

How lifeless particles can become 'life-like' by switching behaviors

from eScienceCommons https://ift.tt/2rdhgVY